|

Up to the turn of the century, Halloween was almost always used with a capital H. While that is still the most common spelling by far, the lowercase variant and Hallow's Eve are gaining prevalence. Other alterations that have actually decreased to today include Hallow e'en, Hallow-e'en, Hallowe'en, and Hallow's eve with a lowercase e. Many people also call it All Hallow's Eve to be ironically archaic, but this is the most accurate spelling of them all. You see, Halloween is a shortening of All-Hallow-even, a Scottish English term describing the evening before All Saint's Day, where mischief was supposed to abound and the witches come out. Sound familiar? This is from a linguistic abomination in Old English, ealra halgena, which also referred to the night in question, but at this point was talking about a pagan holiday that occurred on that very date. So, I guess that since we're all celebrating a pagan holiday, we're paganists?

0 Comments

6,500 years ago, people were using a word that sounded like dheygw as the phoneme for "fasten" or "fix". This Proto-Indo-European primordial mess then evolved into Latin figere, with the same meaning. Borders are fixed boundaries, so this became finis, meaning "border", which took on a metaphorical definition of "end" (yes, related to finish). The "end" meaning stuck in Old French under the term fin, and when the Normans invaded England in 1066 CE, they brought the word with them. Being all money-minded, the English molded it into a more monetary meaning: the end of a debt, a "pay-off"- what would later become the fine we know today. However, the plot thickens. Fin took another turn, towards finaunce, which meant "to ransom". I know that's weird, but it basically does the same thing; paying off a fine. Sadly, the meaning grew less illegal over time, turning from "ransom" to "settlement" to "general pecuniary exchange" to finance, the word we know today, that has surprisingly criminal origins. Now you know.

Restive means "incapable of staying still". Well, then why does it have the root rest in it? Isn't that its own opposite? Indeed. Restive used to be its own antonym as little as 500 years ago, and to understand why it changed we need to understand horse domestication. A horse that didn't want to move was called restive, meaning that it stayed still. However, these horses stayed still because they were nervous, and that also was extended to make them jumpy and nervous. From there, you can easily see how the modern meaning evolved, as the other one lost prevalence. Anyway, in Middle English, restive was restyffe, from Middle French restif, still "motionless", from Old French rester, "to remain", which, yes, is from the root rest. This may be from Proto-Germanic, but it was more likely Latin; if the latter is the case, then it is an affixation of re- ("backward", from PIE wre, "again") onto stare ("stare", from PIE steh, also "stare").

A marshal is a military rank higher than general, normally appointed in wartime. The word has come a long way. We borrowed it in the 1200s from Old French mareschal, who was the person in command. Going backwards in time, the meaning shifts from "commander of armies" to "commander of one army" to "commander of a household" to "commander of horses", until we land at Latin mariscalus, which meant "groom", and not as in the type getting married. This shows how, throughout time, this term really rose in rank, as its prototype became associated with more and more power. Mariscalus is from Old High German marahscalc, a combination of two Proto-Germanic words, markhaz (from Proto-Indo-European markos), "horse", and skalkaz (from PIE skelh, "to split"), "servant". Together, a marshal is a "horse servant". Wow, he really rose up the social ladder. Sadly and surprisingly, there is no connection between marshal and martial.

In a previous post, I proved that man used to refer to either gender. It's the same story with girl! In Middle English, the word we now associate as a "young female" was slowly developing away from a meaning of "young human", but another interesting part of this is the scale of phonetic change that took place. There were variations such as gyrle, girle, gerle, and gyrele on record since Old English; as such a basic word, everything under the sun has been attempted, and you can see that for other simple Germanic terms as well. It is likely that all of this harkens back to Proto-Germanic gurjwaz, still meaning "child" in general, which in turn derives from Proto-Indo-European gher, which was surprisingly appropriate in definition, meaning "short". Gal is a slang pronunciation of girl, first coined in 1795, and when girlie was coined in 1942, it referred to those pulp magazines with provocative pictures.

Yesterday we discovered that sinister means "of the left hand", so today we explore its counterpart on the right. I'll spoil it for you off that bat: it's dexterous. Now, many adjective are just nouns modified a bit, and this is no different. Dexterous showed up in 1600, from the noun dexterity, which was borrowed in the 1520s from dexter, meaning "right". Today, of course, dexterity means "skill with the hands", and since most people were more skilled with their right than their left hands, the meaning changed. Dexter (from whence the boy's name, as well, though it went through a surname first) through Proto-Italic deksteros, goes all the way back to the Proto-Indo-European root deks. which also meant "right". Since 1600, the word dexterity is more common than sinister, which is more common than dexterous. Something sinister is up; something's not right.

We get our word sinister ("evil") from Middle English sinestre, which meant something more along the lines of "unfavorable", and that is from Old French sinistra, which meant "left". There's a lot to explain here; the transition from "left" to kinda "unlucky" occurred because the left hand is associated with clumsiness and abnormality among right-handed people, who got to name the word, and the meaning merely amplified to "evil" over the centuries, to get to today's words. Anyway, sinistra comes from Latin, where the word once again takes the form of sinister (I know, it was much ado about nothing). The suffix is not -er here; this is not Germanic. The suffix is -ter, formed as a counterpart to dexter (we'll get to that tomorrow), and the root is a mystery to etymologists, but we theorize that it goes back to a Proto-Indo-European word, because it may have a Sanskrit cognate.

Central America has its cartels, Italy its mafias, and Japan its yakuza. But where does the word yakuza come from? Obviously Japanese, but to go further one must know the card game Oicho-Kabu. It's very traditional, played with a set of kabufunda cards. The worst possible card combination you can have in the game is an eight, nine, and three, or in Japanese, ya, ku, and za (pronunciations of numbers vary in Japan; these are the forms used here). Therefore, yakuza is something extremely "unlucky", very much like crossing the yakuza. As separate components, ya, ku, and za don't go very far etymologically (being so simple); they simply trace back into Japanese, or Chinese, or Korean, or a mixture of all three, retaining their definitions as they do so. Side note: the yakuza are also called gokudo, but they call themselves ninkyo dantai and the police call them boryokudan.

Something frivolous is, in today's context, either unimportant or not serious. Along with all the other Renaissance borrowings in the 15th century, this came from Latin, in this case the word frivolus. Frivolus carried more of the "unimportant" connotation but still had a side, metaphorical meaning of "silly". The meaning gets more focused as we travel backwards to frivos, which meant "crumbled", from friare, "to crumble". This connection exists because something unimportant breaks easily, and unimportant things are often silly, so what the hey. Friare apparently is related to a whole host of other Latin words, all of which derive from a reconstructed Proto-Indo-European root that sounded like bhreie and meant something super ubiquitous, like "cut" or "scrape".

Due to its characteristic red-and-green colors and an association with the three wise magi, the poinsettia is a staple when it comes to Christmas decorations. But did you know that the poinsettia wasn't introduced into America or English until 1828? It was brought over by the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, and botanists took to it right away, creating a genus name by it in 1836, a name used to today. Now, that aforementioned ambassador was named Joel R. Poinsett, so you can probably see where the word comes from. Poinsett as a surname comes from either the Netherlands or northern France. The best sources I could find on this were pretty vague, but this might be from French poinct, which if true, would be connected to English point and, through Latin punctum, go back to the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European root pewg, which meant something like prick".

When researching my post on coddle, I found that something else that's unexpected derives from the Proto-Indo-European word for "heat", kele. I guess you'll just have to read on to find out what! Kele later became the Proto-Italic root kaleo, also "heat", and we venture out of the realm of reconstruction as the history of the word develops on to calere, the verb form of all this, meaning "to be warm". Added to the verb facere ("to do"), this became calefacere, or "to make something warm". After some international mangling, calefacere became chaufer in Old French, still with the same definition. This retained its spelling for a while, until it became chauffeur. More time passed, and then the Industrial Revolution happened. Engines arrived, and the French needed a name for them. They chose chauffeur because engines heat up with use. Soon, chauffeur became metonymically applied to the people who use them. Now with the definition of "motorist", it's not hard to see why chaffeur means what it does today.

We all know estrogen as a chemical and female sex hormone, but did you know it has sexist origins? When etymologizing it, I immediately recognized -gen as that suffix meaning "producing" (as present in nitrogen and oxygen). I was correct; additionally, through French and Greek, -gen traces to the Proto-Indo-European root gene, "to beget". The estrus root, however, is where it gets interesting. It means "frenzied passion", obviously a sexist reference to women and their hormones. This is similar to the story of hysteria, which meant "uterus". Appropriation abounds! Anyway, estrus derives from Latin oestrus, also meaning "frenzy" but in a less pseudo-scientific sense. Then another twist in the plot line makes everything weirder: oestrus is a borrowing from Greek oistrus, which meant "gadfly", an annoying insect which incites frenzy in some animals. It all is from Proto-Indo-European heys, which was a generally emotional word which kinda meant "anger" but was more complex than that for philologists to understand.

Here's another reason to loathe attorneys: the word doom used to mean "law" in Old English. This was as the phoneme dom, which also meant "judgement" and is present in many terms you should know. The Great Survey ordered by William the Conqueror in 1086 was compiled in the Domesday book (Domesday being an obsolete form of doomsday) because everything was being "judged" by the rightful king. The suffix -dom as in kingdom, fiefdom, and Christendom just means "being judged", by your ruler, landlord, and Christ, respectively. All this dom stuff goes back to the Proto-Germanic word domaz, which etymologists concur meant "judgement" as well. This traces to a Proto-Indo-European word which sounded like dhe and meant "to place". The whole reason doom came to mean "terrible fate" is because of the notion that on Judgement Day, or doomsday, God would punish those who were sinful. Or something like that; you get the idea. I'm a linguist, not a theologian.

A fiasco is a disaster, and you certainly don't want one of those. Yet a mere four hundred years ago, foreign artisans were working to create perfect fiascos. It all goes back to Italian fiasco, which meant "a glass". However, post-medieval glassblowers were very temperamental individuals, often throwing fits and glasses alike when the latter didn't come out perfectly. Through French and then English, a fiasco became known as a "dramatic failure", particularly in the theatre industry. Today, the word has generalized a bit, as you may surmise. Anyway, Italian fiasco traces to Latin flasco, the direct root of today's term flask (also meaning "a type of bottle"), is surprisingly from Frankish, in the form of flaska and still with the same definition. This is from Proto-Germanic fleh, or "to weave", from Proto-Indo-European plek, also "weave" (this probably had to do with the non-glass construction of early flasks). So next time you accidentally knock a museum's fourteenth-century, ruby-encrusted Venetian goblet valued in the millions, you can at least tell the security guards that you were exercising etymology.

If you break down the word sinecure, you can pretty easily discover what it means etymologically. It never was a single word until English (today it means "an easy but well-paid job"); in Latin it was a phrase, beneficium sine cura (somehow the former word got lost in translation), meaning "benefice without care", basically today's definition. Just the sine cura means "without care", reflecting the simplicity of the task. Sine, which we see in sin- ("without"), goes back to Proto-Indo-European swe, "self", and it developed on the sense of "stand alone". Cura you may recognize as being similar to the word cure. This is for good reason; it is the direct etymon of that word; the shared definition is "concern", which makes sense for both venues. This is from Proto-Indo-European kwes, or "to heed". So, if you're truly without caring, in the future you'll call a sinecure "heeding yourself".

The word word has a boring, predictable etymology but it still must be accounted for, if only for posterity's sake! It comes from Proto-Germanic wurda, which meant "word", and that comes from Proto-Indo-European were, which meant "to say". And that's it! Well, not quite. Were also gave way to a development in another language family: the Latin term verbum, which also meant "word" but later meant "verb", and, through Old French verbe, found its way into English in the fourteenth century as -you guessed it- verb. So word and verb are connected! It's weird that they come from different families; verbum mostly left descendents in Italic, and wurda in all the Germanic languages, so the overlap we have in English is pretty rare. Word is much more prevalent that verb in usage over time, but neither have particularly outlandish search interest on Google.

When we hear the word coddle, we think of spoiling child brats, or something along those prototypical lines. But the word's origins go far beyond that; in Middle English it took the form of caudle, meaning "a hot beverage given to disabled people". It changed bit by bit over time to take the current form, along the basis of assisting someone helpless. Caudle before Middle English was a cross-English Channel mutt used in the general Normandy-southern England area, caudel, from Latin calidium, or "warm drink". The root of this, naturally, is calidus, "warm", from whence derived Spanish caliente. Calidus is from Proto-Italic kaleo, from Proto-Indo-European kele, meaning "warm" as well. The point is that most coddled people are kept warm? Whatever. The word coddle has 3,500,000 results on Google and peaked in usage around 1920.

Forget the Breathalyzer: police suspecting people of drunkenness should check eyeliner levels! The word alcohol comes from the Latin term alcohol, which meant "powdered antimony sulfide", describing makeup with the composition of Sb2S3 (which is strange, considering modern alcohols contain OH, but it's all about to make more sense). Later, this sense of "cosmetics" began to mean "any pure substance". Our modern definition of alcohol as in "the drink" first emerged in 1753, and since this contained OH, it was extended in a chemical sense later. These definitions eventually went on to eclipse the "makeup" meaning, because the latter had too many synonyms as it was. Anyway, going back to Latin alcohol, it probably comes from Arabic al-kuhul, or "the kohl", kohl being that type of eyeliner the Egyptians famously utilized. This is from the Semitic root khl, which meant something like "paint" and still had vague connections to antimony.

Occasionally it'll take the form friggatriskaidekaphobia, but that's rarer. Here, we analyze the term paraskavedekatriaphobia, or "the fear of Friday the 13th". The first element, paraskavei, is the Greek term for "Friday" and in Ancient Greek literally meant "day of preparation" as paraskeue. This in turn is a portmanteau of para-, meaning "half", and skeue, meaning "dress". After all, while you're preparing, you're only half-dressed. The second element, dekatreis, is Greek for "thirteen", and is composed of deka-, or "ten" (from Proto-Indo-European dekm, which may be connected to komt, "hand"), and tris, or "three" (also PIE). Finally, phobia is from phobos ("fear"), from phebomai ("to flee"; makes sense), from PIE bhegw, "to run". So, what today means "fear of Friday the Thirteenth" can be broken up into five Greek words meanining "half-dressed three-hand running"!

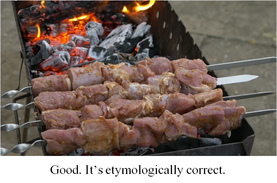

It's clear just by looking at the word kebab that it's not of Indo-European origin. As with many foodstuffs, the etymology of the word follows a similar geographic path as the history of the product's diffusion. So here, we get kebab from Turkish kebap (from whence siskebap, the precursor of shish kebab). This may have passed through an Iranian but Indo-European language in Urdu or Persian, but ultimately traces to Arabic kabab. Here, the noun becomes a verb as we travel further back in time to Aramaic, where kabab sounded like kbb and meant "the action of roasting meat", which most of the time is done on a stick. The Aramaic word is then from a completely hypothesized Afro-Asiatic root kab, meaning "to burn", or possibly just "burnt". It's pretty cool here how kebab travels through three separate language families to get where it is right now.

Remember back in the unicorn post, where I proved that cornus is Latin for "horn"? Well, you might notice that the same root is present in cornucopia. It literally comes from Latin cornu copiae, or "horn of plenty". This mythologically referred to the goat horn that the baby god Jupiter ate out of. As we've already seen, cornu goes back to Proto-Germanic hurnaz, from Proto-Indo-European ker, meaning "horn" or sometimes "head". Copiae, the latter component of the word (which you may recognize as being related to copious; it is, through copiosus, "plentiful"), has different etymologies proffered at my different sources; it could be from com, "with" (from PIE kom, "beside"), or the prefix co- added to the root opis, meaning "wealth" (from PIE hep, "to work", because you work to earn wealth). The second theory makes more sense, I think, but etymology rarely makes sense, so it might as well be the first.

In 1817, the Scottish optical scientist David Brewster submitted a patent for a kaleidoscope, a word he invented. It went on to great success within only a few years, spreading the word far and wide. But where did Brewster get the word from? He created it from joining two Greek words: kalos, meaning "beautiful", and eidos, meaning "shape", obviously so named because of the pretty patterns formed when one looks through a kaleidoscope (additionally, -scope is just a suffix, influenced by telescope, meaning "examine"). Kalos sounded something like kalwos in what was most likely Proto-Hellenic, and in Proto-Indo-European it took the form of kal, also defined as "beautiful". Meanwhile, eidos derives from the reconstructed PIE root weydos, meaning "to see" (this developed from "shape" to "image" over time before ultimately settling on that).

Someone who was feisty in a Middle English context would find it hard to be feisty today. It’s actually quite interesting what happened: we got our current definition in 1896, from feist, which meant “a small dog”. It’s not too hard to draw a parallel to “spunkiness”, for small dogs are unusually manic for their size, and feisty in particular alludes to this one enthusiastic dog breed. But then again, many dogs smell, so it’s also not a surprise when we trace feist to a word meaning “stink”. And you know what stinks? Farts. So, in Middle English, feist meant “fart”. Through Old English, this goes all the way back to fistiz (also “fart”), which probably traces to a Proto-Indo-European word sounding like perd and still meaning “fart”. Of course, the transitions were more nuanced than I'm describing here; for periods in between meanings of feist people were using it for more than one definition, and things generally got confusing.

The word lynch was coined in 1835, and that was an alteration of the legal term lynch law, which referred to justice in any form and didn't necessarily have anything to do with hanging people. This, etymologists concur, was definitely named after someone, but etymologists can't concur who. Some think it was William Lynch, who was some guy from Virginia during the Revolutionary War. Other hypothesize it was Charles Lynch, who was some guy from Virginia during the Revolutionary War. Yes, that's right, but let's get serious. It could've been William because he led some posses against the British, but it also could've been Charles, because he was more famous, yet had less of a violent role, holding court sessions against Loyalists. Whoever it was, Lynch is a corruption of an Irish name, O'Loingsigh, which, if you go far back enough, means "seafarer".

Happy 100-year anniversary of the October Revolution! The word revolution, from Old French revolucion, traces to Latin revolver, which literally meant "to revolve", or more figuratively, a "turning over" of power. The term was first used to describe the Glorious Revolution in 1688, where power was turned over peacefully, but that was soon extended to violent overthrows and coups, which later could also mean "dramatic change" (e.g. the Industrial Revolution). Continuing where we left off, revolver is a combination of the prefix re- ("again"), and volvere, or "to roll". Re- comes from a Proto-Indo-European word that sounded very similar and meant about the same thing, and volvere is from PIE wel, also carrying a connotation of "revolve". Looking at the usages of revolution over time is pretty interesting; the word, of course, peaks when there's an ongoing revolt.

|

AUTHORHello! I'm Adam Aleksic. I have a linguistics degree from Harvard University, where I co-founded the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society and wrote my thesis on Serbo-Croatian language policy. In addition to etymology, I also really enjoy traveling, trivia, philosophy, board games, conlanging, and art history.

Archives

December 2023

TAGS |