|

Sorry to play the devil's advocate, but the Church was trying to reform before the Protestant Reformation. Shortly prior to the 95 Theses, they established the post of advocatus diaboli, a job with a fascinating description: the person had to argue against another person being inducted into sainthood by exposing their faults, flaws, and flukes, to make sure that no one who was unworthy found his way into canonization. This person was appointed because there was rampant corruption and the pope wanted more credibility for the Church. Nice sentiment, but it didn't work out. Years of kerfuffle later, in 1760, a calque on the word was used in English as devil's advocate, and no alterations have been made since. Usage of the word in that form is most common, and Devil's advocate occurs more frequently than Devil's Advocate. Seems that no capitalization prevails, and the same is true for the Latin term. The phrase trended highly when an eponymous 1997 movie came out.

0 Comments

When you call the alphabet "the ABCs", it's etymologically redundant. Our word alphabet is from Latin alphabetum, from Greek alphabetos, both of which were also used to denote a set of letters in a language. Now, the origin here is blaringly obvious: alphabetos is a portmanteau of alpha and beta, the first two letters of the Greek alphabet that we still use for military designations, naming pack animals, describing particles, and the like today. Basically it amounts to calling your ABCs just the ABs. The Alpha letter and word for the letter are both from the Phoenicians (the dudes who had the first phonemic alphabet), where alpha took the form of alb and most likely came from Proto-Semitic, because it may be philologically compared to the first letters of the Arabic and Hebrew alphabets (alif and alef, respectively). Beta followed a similar route: it is from the Phoenician letter beth. Alphabet was introduced in the fifteenth century and replaced an English word meaning "row of letters".

Psst! Did you know that the word gossip has very familial origins? The definition kind of changed throughout English: instead of "rumor-mongering", as it is today, gossip in Middle English just meant "idle talk". Even earlier (now in the form gossib), it meant "confidant", because you engage in idle talk with people you can confide in. In Old English as godsib, it meant "godparent",specifically, because a godparent is also a confidant. This is a portmanteau of god and sib, the latter of which meant "kin" (and, yes, is the etymon of sibling, "brother or sister", just with the addition of the suffix -ling). We've already explored god in an earlier post, but sib, which earlier took the form sibb, traces to the reconstructed Proto-Germanic root sibjaz, which meant "related" and ultimately goes back to Proto-Indo-European swe, or "self". Fascinating!

Beelzebub is synonymous with the devil nowadays, but it used to have such a different meaning. When the word entered English as Belzebub, it described a Philistine god from the Old Testament. This, through Latin, has its origin in the Greek word Beelzeboul, Eventually, it goes all the way back to the Hebrew word Ba'alzvuv, which literally meant "lord of the flies" because the god in question was basically that. Ba'alzvuv is a portmanteau of ba'al, meaning "lord", and zvuv, meaning "fly"; the semantics here are unsurprising. Ba'al has two possible origins: it may be traced to the Proto-Semitic word ba'l, meaning "husband" and "owner" (from which we can draw an interesting comparison to gender roles back then), or it could be named after the Akkadian god Belu. Zvuv, keeping its definition all the way, is thought to be from Proto-Semitic dbb, from Proto-Afro-Asiatic dupp. Anyway, you better watch out for winged insects in the future, because they may report on you to their lord, the Devil.

The word slave, ever important after it entered English in the mid sixteenth century, comes from the French word sclave, from the Latin word sclavus. Both of these words also meant "slave", but the latter originally meant "Slav" (as in the group of people indigenous to eastern Europe), because the Romans originally enslaved, well, Slavs. This is from the Greek word sklabos, from earlier slabenos, from Old Church Slavonic sloveninu, from Proto-Slavic slovenin, which may have several origins, all of them Slavic as well. Indeed, the word Slav followed a similar path into English, all the way up through sclavus and then directly into Middle English sclave before today. The word Yugoslavia means "land of the southern Slavs" (Yugo is from Serbian jugo, from Proto-Slavic jugb and maybe PIE hewg, still "south"). Anyway, the point of all this is that slave meant slav. Whoa.

Chowder was probably invented in Newfoundland by early French-and-English-speaking colonists, and because of this French influence, it is thought that the word developed from French chaudiere, which described a kind of large pot. This is from the Latin word caldaria, also "cooking pot", which is from the earlier Latin word caldarium, which meant "hot bath" and makes sense if you understand cooking as the process of giving your ingredients a very hot bath. This is from an even earlier Latin word, which was alternatively spelled caldus and calidus and meant "hot". As we go further back, linguists reconstruct caldus as being from the Proto-Italic term kaleo, which stems from Proto-Indo-European kelh, still meaning "hot". Once chaudiere was adopted to denote the soup, awesome New England accents altered it so the ch became hard and the ending took on its current form.

In 1966, the word jetlag was first used by travel writer Horace Sutton as a replacement for the previously cumbersome term time zone syndrome. It's quite obviously a portmanteau of jet and lag, so let's see where that takes us. Jet first entered English in the late seventeenth century, but back then it took on the meaning of "a gush" of water or air. It hails from French jet (also get), which derives from Latin iactus, or "throw", an easy connection to make. Iactus is from the verb iacere ("to throw"; another instance of anthimeria), from Proto-Italic jakjo, and ultimately from Proto-Indo-European hyeh, also "to throw". Lag, meaning "delay", of course, takes us into a different language family: we are unsure exactly where from, but all evidence points towards Scandinavia, for it's philologically related to some other North Germanic words. The whole term jetlag is kinda oxymoronic, since it describes something very fast causing some kind of slowing down.

The word pillar is from the French word pilier, which is from Latin word pilare, which in turn is from the earlier Latin word pila. All of these words meant the exact same thing, and they continue to mean the exact same thing as we go back to Proto-Italic pistla and Proto-Indo-European pistlo, Needless to say, pillars have been around a long time, with little need for variation, semantically or in spelling. This changes as we go back to the even earlier PIE root peys, which meant "to crush"; a pillar is stone, and stones are crushed. Now, peys is also the root of several other words. Also through the pistlo route, it's the root of the word pilum (a type of Roman spear that "crushes" its enemies, I suppose), and it lead to the Latin verb pinsere, or "to pound", which later gave way to pestone, a word that meant "pestle" (a tool for grinding stuff; here the connections are clearest), and through both Italian and French, it was altered in phonetics and definition to become piston, an Italian invention. All these things that needed to be created came from naught but crushings. How scintillating!

The word thunder has an etymology that's simple, short, and sweet: it's from Old English thunor, from Proto-Germanic thunraz, from Proto-Indo-European tenh. It's the connections we can draw from this that are fascinating. Probably with a jaunt through Proto-Italic, tenh landed itself in Latin in the form tornare, still "to thunder". This developed into the Spanish word tronar, which later became tronada, now with a meaning more like "thunderstorm"; not that far of a stretch. Then, in the mid-sixteenth century, English sailors picked up the term from Spanish sailors, but accidentally combined it with the verb tornar ("to twist"), so that they switched the r and o sounds. This mutt of a combination formed tornado, which is oddly appropriate, considering it is a twisting thunderstorm. An alternative spelling of ternado was also created but never caught on.

We get the word idiot directly from French idiote, from Latin idiota. The former word meant "dumb person", but the latter meant more along the lines of "uneducated person", which makes all the difference as we go further back to Greek idiotes, or "commoner" (a case where, as we've seen before, the highborns who could read created derogatory words for the lower classes). Since the Greeks had democracy and considered the commoners private citizens, the connection existed for the term to trace to the earlier idios, meaning "private", probably from Proto-Indo-European swe, defined as "self". Now, the word idios also gave way to another Greek word, idioumani, which had the complicated meaning of "something that is privately peculiar". As this became Greek idioma, it meant something more like "peculiar", but still described things that are unique to small groups. This definition stayed through Latin idioma, French idiome, and finally English idiom. So it may be idiotic, but two words in this idiom are peas in a pod.

There are many kinds of persimmons, from all over the world. There was already a word for them (diospyros) when new colonists in the Americas encountered a new type in Virginia, but they borrowed a Powhatan word to classify it: pichamins, which also took the form of pushemins, and pasimenan, all of which described the fruit/flower and had a literal meaning of "dry fruit". Powhatan is part of the Algonquian family of languages, and the -imen- part of the word seems to go back to a common Proto-Algonquian root, imin, which meant "fruit" or "berry", possibly going all the way back to Proto-Algic mene, also "berry" (Proto-Algic is a little-researched and hypothesized tongue encompassing Algonquian and several lesser families). The pas- prefix and -an suffix like as not took a similar route. Usage of persimmon peaked around 1940.

When the word savage entered English in the thirteenth century, it was in the adjectival form. Savage as a person goes back to the fifteenth century (and emerged from the former), and the verb to savage is from the nineteenth century. All of these forms go back to the French word sauvage, which earlier on took the form salvage (different origin than the English word; I checked). This meant "untamed", much as today, and hails from its Latin cognate salvaticus, which is a slight modification of the earlier term silvaticus, which figuratively meant "wild" and literally means "of the woods" (that connection is clear), from silva, "forest". This goes back to the Proto-Indo-European reconstructed root sel, which meant "frame", "board", and had several other wooden connotations as well. Unironically, as society has grown more modern since the 1800s, the word savage lost usage.

Father has always been the formal way of referring to your male progenitor, but in recent years both dad and daddy have been gaining in usage while it flatlined well above them. The words dad and daddy were likely fathered by the Middle English words dadd and dadde, both of which have an uncertain origin. It is likely the words have been around in English much longer and simply were not recorded, so some etymologists theorize that it traces to Old English atta, also aetta, possibly from Proto-Germanic atto, meaning "father", and ultimately from Proto-Indo-European atta. However, it is difficult to ascertain whether such a straight line of evolution exists, because similar sounds with a's, d's, and t's also mean "father" all over the European continent. Maybe the word has just been floating around for a while. There certainly has been very little variation in all languages, both phonetically and semantically: tracing it through philology is therefore hard.

The word pumpernickel has a fascinating etymology on so many levels. Firstly, it’s rare to find Germanic words in English that start with a p; because of Grimm’s law, they normally begin with an f. But that’s the boring part. The fun part is that it goes back to two Westphalian words, pumper, which meant “fart”, and Nickel, which was a proper noun that meant “goblin” or “rascal”. Yes, the bagel you’ve taken for granted in the past is really naught but the gas of gremlins. Originally it was meant as an insult, because people at first didn’t like the new kind of bread (but the name stuck even once it caught on). Anyway, pumper has an uncertain origin, but Nickel (which is also the origin of the word for our 5 cent piece; see my elements infographic) traces to the earlier name Nikolaus, which probably goes back to Greek Nike, a name that meant “victory”. So even that changed a lot. Both words definitely are from Proto-Indo-European. I still can't get over that mind-blowing origin!

Harry Potter fans and Times Square 'psychics' alike can tell you that tasseomancy is the art of reading tea leaves. But can they explain the fascinating origins of that word? First, we can break off the Greek suffix -mancy, which literally meant "divination" (so tasseomancy is a narrowing down of that larger field). This is from the earlier word manteia, which meant "oracle", from mantis, "seer", which somehow goes back to the Proto-Indo-European word men, which we've seen before and meant "think". Tasse-, on the other hand, hails from French, where it meant "cup" (thus tasseomancy was "cup divination"; the o belongs to neither, by the way). This is -ooh- from Arabic tas, "cup", eventually from Proto-Indo-Iranian tas, which meant "to make", since one makes cups, supposedly. Curiously enough, there is a little-used and outdated word in English spelled tasse which meant "a piece of armour", though it originally meant "pouch", and though it also shared the meaning of "a kind of container", it has a completely different origin, going through the Germanic languages to Proto-Germanic tasko ("bag") and ultimately the Proto-Indo-European term das, or "to fray". Weird; who could've predicted that?

In 1935, George, Thomas, and John Dempster invented a handy-dandy garbage receptacle that was, shall we say, industrial-sized. They called this the Dempster-Dumpster. Eventually, the Dempster part of the eventual trademark was lost to the ages, but dumpster remains in our vocabulary up till today. The word dumpster is a pretty catchy portmanteau of the word dump (obviously) and the last part of the Dempster surname, just to make the company's new product acoustically pleasing. The word dump, which in context most likely took the meaning "where garbage is put", but had many other definitions as well, comes from the verb form of "throwing something down or away" and by this meaning can be traced back to the Old Norse sound dumpa (which meant "thump", and is also probably the etymon of thump itself, a word with many relatives and few ancestors), probably of imitative or onomatopoeic origin. Dumpster is no longer a trademark (as it expired) and no longer has to be capitalized, so lucky you! You've been unwittingly adhering to copyright law.

Mollusk is used in North America, but mollusc is the common European spelling. The latter probably developed first, but in any case, both of these terms derive from French mollusque, which is, as many animal names are, from Carolus Linnaeus (see infographic), who first noted the word mollusca in 1783 when he was being a nerd and categorizing everything. This he borrowed directly from the Latin word molluscus, which meant "thin skinned", from the root mollis, which meant "soft". This is especially ironic, when you consider that some mollusks, like snails, have pretty hard shells. Mollus may be a corruption of an earlier word molduis, which through a brief jaunt in Proto-Italic goes back to the Proto-Indo-European term moldus, which in turn can be followed to the earlier Proto-Indo-European mel. All these following words meant "soft" as well, but they lead to words from Prussian maldai ("boys") to Ancient Greek bladus ("weak"). So, yeah, pretty interesting!

Ever considered the similarity in structure between macaroon and macaroni? In fact, the two words are connected: macaroon (through French macaron and Italian maccarone) and macaroni (through Italian maccaroni) both trace to the Italian word maccherone, which described a macaroni-like pasta. Obviously it was macaroon that went through a semantic shift here; it was named after the pasta because macaroon cookies utilize coconut or almond shredded in a manner reminiscent of macaroni. Now, maccherone has two possible origins, each as vague as the next. It may be from the earlier Italian word maccare, or "to crush", or it may be from the Greek word makaria, which meant "food with barley", perhaps since the original pastas were made with that vegetable. Both words have uncertain origins. Later, the word macaroon deviated much farther from its original meaning as it came to be the term for a sort of French cookie that had nothing to do with shredded bits. Ah, how languages change!

When you hear the name medusa, the first thought that runs through your mind is of the gorgon. Well, there's more to the word, in the past and present. Medusa is a name as Greek as the myth, but the word goes back to Ancient Greek medein, "to protect" (that's, ironically, just how the name worked out). Probably through Proto-Hellenic, this traces to the Proto-Indo-European root med, which meant "to take measures", since protection requires taking measures to ensure it be so. Med is also the root of the English word mode, through Latin modus and Old French mode. Now, the word Medusa has been in English for a very long time, but a newer definition emerged when Carolus Linnaeus used it to describe a jellyfish species, and indeed the name still exists today. So two descendants of the Greek word for "protector" do exactly the opposite of protecting: one petrifies, the other stuns. Weird.

Shakespeare invented swagger. No, really. He did. In his 1590 play A Midsummer's Night's Dream, Puck says "What hempen homespuns have we swaggering here?" This is probably taken from the Old Norse word sveggja ("to sway"), which is probably from the Proto-Germanic word swingan ("to swing"), which is probably from the Proto-Indo-European word sweng ("to turn"). Anyway, when Shakespeare used it, swagger meant "walking pompously". Pompous people often decorate themselves with, and use, ornaments, or something? So somehow the word developed into "material", though it also kind of meant "cool" in colloquial terms, as developed from "pompous". Acronyms for the word, such as stuff we all get and secretly we are gay are apocryphal, and by now alterations have appeared, like schwag and swagg. It's complicated. Swagger also still exists today.

A long time ago, in this galaxy, near-primordial savages across parts of Eurasia were using the word men to describe the action of "thinking". This Proto-Indo-European term went into Ancient Greek as mnestis, which changed slightly, semantically, as it took on a meaning of "remembering". This may seem familiar, because when added to the prefix a- ("not"), the word becomes amnestos, or "forgotten". This is connected to the word amnesty through Latin amnestia and French amnestie, and makes sense because in an amnesty the past crimes of a person are forgiven by whoever is doing the pardoning. Meanwhile, the Greeks made the word amnesia, also from the a- prefix and a conjugated form of mnestis, to create a word that meant something more along the lines of "forgetting" than "forgotten". Amnesty entered English two hundred years before amnesia.

When you dial a number on your telephone, you're barely conscious of the intricate history of the word. The verb dial, naturally, goes back to the good ole days when to call someone you actually had to spin a rotating dial to input the number of that person. This telephone dial was first attested as a word in 1879, and the word dial itself carried connotations of circular motion since it was used to discuss sundials. Since sundials tell the time of day, it is unsurprising that the word dial traces to Latin dialis, which meant "concerning the day". This is a conjugated form of the word diem (as in carpe), from Proto-Italic djem. Though etymologists are never quite sure about these things, djem is reconstructed as originating from the Proto-Indo-European root dyem, still "day". The noun-to-verb switch we see here is fairly common, and it is called verbification, a subordinate concept of anthimeria, when a part of speech changes.

The word sniper obviously utilizes the -er suffix denoting a person; thus a sniper is one who has snipes. This is pretty close to the etymology; we all know that a snipe is also a word for a hard-to-catch bird, and in the olden days a sniper was a sharpshooter who was skilled enough to bust a cap in that particular kind of bird. In Middle English this word was snypa, and in Old English it was spelled snipa. This is from its Old Norse cognate snipa. This occasionally showed up in the form myrsnipa, which literally meant "moor snipe", and is of uncertain origin, though it is probably ubiquitous to Germanic languages and is definitely a word that traces from Proto-Indo-European (compare with the Latin genus name Scolopacidae). Usage of sniper only overtook snipe in the 1970s; current usage doesn't even come close to the peak of snipe in the 1800s.

The usage of the word cracker as "hard biscuit" comes from the action of cracking it in two. The word cracker as a derogatory insult for "county bumpkin" has origins in the action of these farmers cracking their whips towards their slaves and mules (I condemn that, just so you know, ACLU and PETA). Both of these words therefore go back to the same verb; that verb in turn goes back to the Old English word cracian, which carried the definition "to make a loud noise". Most Old English words go back to Proto-Germanic, and this is no exception: cracian traces to PGmc krakojan, which may have taken a detour through Proto-Indo-European gerg, "to shout" but definitely is of either imitative or onomatopoeic origin. Interestingly enough, cracking codes is actually a play on words and has different origins; it modified the word hacking to make it seem more acceptable.

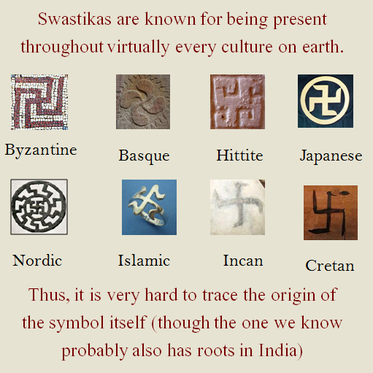

Almost everybody thinks that the swastika used to be a Tibetan peace symbol, but let's go in depth. While we're not even completely sure where the symbol comes from, the word the Nazis borrowed that describes the symbol is definitely from Sanskrit svastikas, which meant "being fortunate" (the irony only gets worse). Obviously this definition is one of the reasons Hitler picked the design. Other reasons include recent popular excavations by archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann and the Aryan identity associated with the emblem. Anyway, svastikas is a portmanteau of the word su, which meant "good", the root ati, which meant "to be", and the suffix ka, which carried many meanings like "soul" but in this case is just a diminutive. Since ati and ka are just modifiers, the only important remaining trace to do is the link between su and the Proto-Indo-European reconstruction esu, which meant "good". A lot has changed in the connotation of the word since then, that's all I'm saying.

|

AUTHORHello! I'm Adam Aleksic. I have a linguistics degree from Harvard University, where I co-founded the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society and wrote my thesis on Serbo-Croatian language policy. In addition to etymology, I also really enjoy traveling, trivia, philosophy, board games, conlanging, and art history.

Archives

December 2023

TAGS |