|

I get way more requests than comments. It's unfair. The word behemoth, as the title implies, has origins in the Bible, where in the book of Job it, alongside the Leviathan, is cited as an example of God's power in creating dangerous creatures. Both monsters later took on a metaphorical usage as "big things", but behemoth specifically is a transliteration of Hebrew b'hemoth. This has several suggested sources, each equally ambiguous and arbitrary. The prevailing notion is that it's a corruption of b'hemah, or "beast", itself probably from a Proto-Semitic root like bhmt that carried connotations of livestock. Another theory is that b'hemah is from Egyptian pehamu, which meant "hippopotamus", a dangerous creature revered by their ancient culture. Even less likely roots have been suggested across the Semitic languages, though all trace back to some kind of bulky animal. All the spellings here are loose phonetic transliterations (remember, no vowels in Egyptian and Hebrew for real) and all go back from Proto-Semitic to Afro-Asiatic.

1 Comment

Pavilion ("a building with open sides") comes from Anglo-Norman pavilloun, from Old French paveillon, which in more recent times had the same meaning but once meant "butterfly". Yes, you read that right; this curious change in definition arose because the original pavilions, which were tents, bore some kind of a resemblance to butterfly wings, enough to merit such a name. It was too early at this point for the "butterfly" translation to enter English, but it did survive as the modern French word papillon (itself the precursor of the dog breed papillon, literally "butterfly"). Anyway, All this goes back to the Latin word papillionem, which doubled in meaning as "butterfly" and "moth", which comes from Proto-Indo-European pal, "to touch". Usage of both papillon and pavilion have plateaued over time. Next time you're at a company picnic or something, make sure your covered area doesn't fly away.

We all know a hobo as a vagrant or tramp, ubiquitous among 1930s train squatters. There are three possible origins of this word. One is that it's a contraction of the exclamation ho, boy!, which was a call used at workers on the railroads back when they were serious about building them. Mostly vagrants would be doing this kind of work, so that's how the association occurred. Another possibility is that it's a contraction of hoe-boy, a term so named because wandering homeless people in the olden days often took on jobs as farm hands. The final possible etymology is not associated with a single profession; rather, it's from the word hawbuck, an archaic term for a "country bumpkin", but that in itself has an obscure etymology. It's hard to know for sure, but hobo seems to be nothing more than a pure Americanism, with origins as unknown as that of a real hobo.

Newfangled, a word old geezers use to describe those darn modern devices, is a very strange word if you think about it. The only surviving member from its Old English family, which included such words as andfangol (“undertaker”) and underfangle (“hospitality”), it’s essentially compromised of the prefix new- and the verb fangle, a remnant of yore which, going back in time, meant “novelty”, then “manufacture” (so something newfangled was newly manufactured), then, as fangel, “inclined to take”, and finally, in the form of Proto-Germanic fanglon, meaning “to grasp”. That Proto-Germanic word, by the way, would later produce fon “to seize”, which in turn is the etymon of fang, as in “sharp tooth”. Most likely this all traces back to the Proto-Indo-European reconstruction pehg, "to fasten". In the end, the most whimsical thing about newfangled is how old the word is.

Wow! Not only is the etymology of pudding rife with fascinating semantic change, but it violates linguistic laws as well! As early as the fourteenth century, it was spelled poding and meant "sausage". How did this shift in definition occur? The first puddings were boiled in bags much resembling a sausage in a skin, and people couldn't resist applying that meaning. Eventually the "sausage" definition faded away. Now, it's extremely rare for a French b to English p switch to occur among the first letters, but pudding does it anyway, tracing back to French boudin. What a rebel. Boudin is from the Latin word botellus, meaning "a small sausage", from botulus, regular "sausage". This has been reconstructed as deriving from the theorized Proto-Indo-European root gwet, a "swelling". Seriously, though, pudding is an etymological gold mine! Or should I say sausage?

Magazine the ammunition thing and magazine the reading material are connected, but probably not how you would expect. Let’s start with the “publication” definition. The first magazine was named after a previous usage of magazine, meaning "a list of military information", specifically information about ammunition. This comes from another previous usage of magazine, the one meaning just "ammunition holder". It's weird. Anyway, it gets weirder as we go back, for the meaning of "ammunition storage" becomes something more like "supply storage" in general, a meaning which traces to Middle French magasin, or "warehouse". I know; the semantic change is incredible on this one. Through Italian magazzino, this goes back to Arabic makhzan, which had smaller connotations, more like "storage space". This is ultimately from kazana, the root which meant "store" and probably comes from Proto-Semitic, from Afro-Asiatic.

Romance novels were around before actual romances. The usage we know as "love affair", or, in its verb form, "to love", was first attested as late as 1916. Before that, it just meant "adventure", since love is an adventure, I suppose, and prior to even that, it meant "adventure book", the kind with knights and heroism. During this time, the spelling evolved from romaunce, and the original roumances were not affixed with a "novel"; the word in itself implied "novel". This definition survived to today: "What are you reading?" "Oh, a romance." Romaunce as a word is obviously French, and it comes from their term romanz, which was the name of the vernacular language of France at the time. Yup, the book genre was named after a language. This, from Vulgar Latin romanice, is related to our term "romance languages", which describes existing Italic tongues and has nothing to do with "languages of love", a popular misconception. Romanice is from romanus, the demonym for "Roman", from the root Roma ("rome"), possibly of Etruscan origin!

Lapis lazuli is a sought-after stone the color of azure, which is often used as jewelry. Since the eighteenth century, the abbreviation lazuli has been present, but the full name has stuck around since the 1600s, when it came as a direct loan from Medieval Latin lapis lazuli, with a rough translation of "stone of the heavens". I'm not concerned with lapis, the "stone" part, but lazuli is from the singular lazulum (just "heaven", obviously), which comes from Arabic lazuward, which, curiously enough, meant "azure"! At this point you might guess that the color azure also traces to this word. You would not be wrong: the French took the subsequent Greek word lazour and mistakenly separated as they do, l'azour. Then they dropped the determiner, it became azur, and we took it into English as it is. Going back to lazuward, we can trace the history of both lazuli and azure to Persian lajavard. This, by the way, isn't Iran; it's eastern Afghanistan and southern Tajikistan, and lajavard ultimately is named after a village in the area, Lazvard, where azure lazuli was first mined. Weird how over two thousand years, so much changed around the (-)azu- that center both words.

While you're assessing something, you may be etymologically assessing too. The word we know as meaning "consider" comes from Old French assesser, from Medieval Latin assessere. Going backwards even further, we see the word become asidduus, which meant "to sit down to"! Cool how that works out; you certainly sit down to think about many things. Eliminate the not-to-obvious prefix ad-, meaning "to" (a word so simple it doesn't deserve an origin, since it basically remained itself throughout history, except for this moment) and we're left with sedere ("to sit"), a root I've already etymologized like ten times (a lot of words derive from it) but might as well trace again; through Proto- sedeo, it originated from Proto-Indo-European sed, also "sit". In other news, asidduus (that Latin word from earlier with the hidden ad-) is also the etymon of assiduity, a pontificating word vaguely meaning "diligence"! I guess you need to be seated to be diligent! Yay!

The dog days of summer describe that general time between July and August when it's hot you're feeling lazy as a dog. Many people think that's where the word comes from, but it gets a little more involved than all that. In fact, the dog days occur because of an astronomical reason: they happen when the star Sirius is in the night sky. Only recently was an association with heat made! Dog days as a phrase is a calque on the Latin term dies caniculares, which translate literally into our saying. But why the connection between Sirius rising and dogs? Well, as any Harry Potter fan can tell you (and this is one hundred percent true), Sirius is Latin for "dog", and the star Sirius is often referred to as the "dog star". Thus the correlation. Interestingly enough, the rising of Sirius has shifted over time; during the times of the summer solstice, it peaked around mid-June instead of August. Perhaps that's why the heat link was forged later...

Today marks one of the greatest eclipses in modern American history, so this seemed appropriate. The word eclipse as a verb and noun both comes from its Old French cognate eclipse, which took the usual route through Latin eclipsis to trace back to Greek ekleipsis. It isn't surprising that it derives from Greece because of all those fancy astronomers naming stuff in the Classical Age, if you think about it. Anyway, ekleipsis derives from ekleipen, which once meant "a forsaking or abandonment" (of the sun, makes sense) but more literally had a definition of "leaving out". Etymologically it meant that too: the prefix ek- meant "out", from the previously covered PIE root eks (also "out"), and the root lepein meant "to leave" and may be followed to another Proto-Indo-European root; leykw, also "leave". Recent google trends saw "eclipse" searches skyrocket, though long-term usage has actually decreased somewhat.

Cats may have nine of them, but amphibians lead double lives. Clearly a Hellenic word, amphibian comes from Greek amphibios, a word which correctly translates to "living a double life". This, of course, refers to how the animals live both inside the water and outside of it, but that didn't stop this more metaphorical meaning arising. Amphi-, which means "of both kinds", traces to the Proto-Indo-European word ahmbi, or "round". Bios, which you should recognize from the prefix bio- as meaning "life", comes from the Proto-Indo-European mutt gwihwos ("alive"), from the earlier root gweyh ("live"). Interestingly enough, until zoology was beginning to get standardized at the onset of the nineteenth century, amphibian referred to any animal that spent time in and out of the water, including hippos, dragonflies, and crocodiles!

The word blurb, meaning "a short description", is now seriously used by advertising agencies and Silicon Valley corporations who want to appear hip. Little does everyone realize that those short short-outs secretly satirize stuff! The word blurb first appeared in 1906 but was popularized by comic writer Frank Burgess in his book Are You a Bromide? In this titillating tome, Burgess featured a woman on the front cover named "Miss Belinda Blurb" who (along with the caption in the act of blurbing) shouts out "Yes, this is a blurb!" The whole affair was meant to poke a little fun at the habits of publishers to use short catchy quotes and "damsels" on their books' dust jackets. Queer as the joke may seem now, it was pretty popular then, and blurb caught on, with its fastest rate of growth until 1936 and a steady rise afterwards. The rest is history. Literally.

The etymology of the word ammunition is a pretty good case for the Second Amendment. Commonly abbreviated ammo, it first appeared in the seventeenth century as a faulty breaking up of the French phrase la munition (however the similarly surviving English word munition was correctly brought over the Channel). By the way, I should note here that ammunition and munition did not always refer just to armaments, as the words do today. In olden times, they referred to military supplies in general. And before, in Middle French as municion, people would fortify with military supplies, so the word meant "fortify". This comes from Latin munitionem "defending, fortifying", which is a conjugation of munire, a verb meaning "to defend". This traces to moeina, "defensive wall", from the Proto-Indo-European root mei, which meant "to build or fix". My point here is, though, that etymologically speaking, ammunition is only used for defense.

The word amalgam today can be used in political or literary commentary to describe a fusion, a blend of things. However, that definition used to have a much more literal definition, and still does, somewhat. More recently, amalgam has described liquid mercury alloyed with other metals to cover cavities (less used nowadays, mercury being bad and all stuff), and before that, it just meant "a blend with mercury" in general. This is from the French word amalgame, from Latin amalgama, both with the same meaning, in an alchemical context. Somewhere in Roman times, this mutated from earlier malagma (which meant "plaster", and earlier "poultice"); probably a misspelling or otherwise accidental alteration. Finally, malagma goes back to the Arabic word malgham, a "poultice for sores", which developed from Ancient Greek malakos and the Proto-Indo-European reconstruction mel, also "soft". That dip through another language family was interesting, as was the observation that amalgam is an amalgam of phonetic alterations.

The word sabotage has origins so strange it's as if somebody sabotaged its etymology. As it traces back to the French verb saboter, the meaning gets less and less intentionally malicious, until it finally just meant "to mess up". And before that? It was spelled sabot, and meant "wooden shoes"! This change occurred because people with wooden shoes were often clumsier than normal and caused workplace accidents (later, of course, the "workplace accidents" definition became deliberate, but that's not much of a change. The linguistics also get interesting here, because sabot may have Turkish origins (etymologists think the Ottoman word zabata). We're not sure, but it definitely shares a root with Spanish zapato, Italian ciabatta, and words meaning "shoe" in Middle Eastern languages. It doesn't seem Indo-European.

Many pundits used the term jingoism to describe extreme nationalism, usually in a far-right context. This, like its fellow conjugations jingoist, jingoish, and jingoistic, stems from the root jingo, a less commonly used word nowadays, but one that meant "a patriot hawkish on foreign affairs". This usage came from a British nationalistic song where they say "by Jingo!" in describing their military. Before that, by Jingo was an expression that basically stood in as a euphemism for Jesus. While Jingo may just be a corruption of the name of the Christian Messiah, an interesting alternative etymology has also been proposed. Though evidence is scarce, some think that jingo came from the Basque word jinkoa, which meant "god". This would be fascinating, because (of course), Basque is not an Indo-European language and comes from its own family, Proto-Basque. It's probably from Jesus, though (like how gosh is a euphemism for god). Meh.

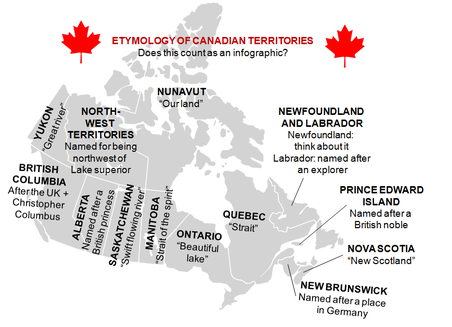

Nunavut. The largest Canadian province, yet least dense in population. In the local Inuktitut (a language you may remember from kayak) tongue, it was all in lowercase and meant "our land". From there, nunavut can be split up into the root nuna, meaning "our", and the suffix -vut, which filled a role as a plural possessive just like our our. Nuna has cognates in basically all of the Eskimo-Aleut family, and goes back to Proto-Eskimo luna, also "land". -Vut undoubtedly is also from Proto-Eskimo. The point of this all, though, is to point out that Nunavut, though largely Inuit, is a Canadian territory, so it's not really that of the Inuit people anymore. Irony strikes through etymology. Since negotiations to create Nunavut only started in 1976, usage of the name has increased since the 1940s.

Throughout English, tiger was taking its place as it competed with other forms like tyger, tigre, and tygre. All four of these variations come from the Old English word tigras, from French tigre, which in turn derives from Latin tigris, still meaning "tiger". This is likely the source of the name of the famous Mesopotamian river, as well. Tigris is from its Greek cognate tigris, which most likely goes back to the Avestan word for "arrow", tigri (since a tiger pounces on you like an "arrow", all quick and deadly). Avestan, being an Iranian language (in which Zoroastrian scripture was written), has a lot of its words go back to Old Persian, and this is no exception. Tigri is theorized to trace from tigra, a word that meant "sharp" or "pointed" and has an obvious connection to "arrow". Rather than going back to Indo-Iranian and Proto-Indo-European, this then takes a turn into another language family, towards Sumerian, but that's all we know.

In 1743, we borrowed the word umiak from Denmark, and in 1757 we borrowed kajak from there. These terms are clearly not Germanic: they were in fact borrowed from the Danish colony of Greenland (which is STILL its colony, and NOT a country). A kajak, or later kayak, was a covered boat, and an umiak, which hasn't quite caught on to its brother's popularity, was basically the Eskimo equivalent of a canoe. Both of the words come from the Inuktitut language; kajak from quyaq, or "man's boat", and umiak from umiaq, or "woman's boat". These refer to the genders allowed to paddle each kind of vessel; there were surprisingly strict rules about that. Both words, as are basically all Inuktitut words, derive from the theorized Proto-Eskimo language. Usage of the word kayak is more than 30 times more prevalent than umiak, and it's increasing exponentially, while the latter is not.

I have no clue whether this has anything to do with the French president, but that's an interesting thing to think about here. A macron is a linguistic term for a horizontal diacritical line placed over a letter, usually used to mark heavy syllables. The word macron is from the Greek term makron, a conjugation of earlier makros, which meant "long" (kind of an etymological oxymoron, since a macron today is a rather short dash) and is the etymon of the prefix macro-, meaning "on a large scale". Makros definitely came from Proto-Indo-European, but the reconstruction varies with sources; it could be something like mak, mhkros, or mehk, all of which have a prominent m and k and mean something like "long" as well. Usage of the word has flatlined since 1880, but usage of macro- has dropped since 1990.

The word spunky (first attested in 1786) means "having the quality of spunk (first attested in the early sixteenth century, and, nope, no connection to punk)". Spunk, meaning something like "spirit" today, took a metaphorical shift from its earlier meaning of "spark". This is a combination of two other words: spark, meaning "spark", and funk, an obsolete word meaning "spark". That may sound a little confusing, so let me clarify: SOMEBODY COMBINED TWO WORDS FOR SPARK TO MAKE A THIRD WORD FOR SPARK. Obviously the definition has evolved from then, but that's literally what happened when the spunk first came about. Funk, a pretty basic word, went through alterations all the way back to Proto-Germanic, as funke, fonke, funca, fanca, funko, and fanko, continuously retaining its definition. That is, until we trace it to Proto-Indo-European peng, "to shine". I'll save the word spark for another occasion (the winning definition survives). Just take in this crazy portmanteau.

The word reggae was popularized by a Jamaican band called the "Toots and Maytals", who named a song Do The Reggay. Soon afterwards, reggay changed (as words do) to become reggae and applied to the style of music propagated by the Toots and Maytals. Before that, though, reggay was known as the rega-rega, which meant "a protest" and was applied to music because it was people's way of expressing themselves. Prior to even that, it was raga-raga and meant "tattered clothes" or something similar, and (I couldn't find any research on this, so I'm just guessing) may be etymologically connected because of a correlation between poverty and protests. At this point, you may have noticed that raga-raga looks like a super-Jamaican-English version of the word rag ("tattered cloth"). This in fact is true! Continuing backward, rag had several alterations in Middle and Old English, going through forms like ragge, ragg, and raggig after ultimately deriving from Old Norse rogg, or "tuft". This may be from Proto-Germanic ruhwaz, "rough", with a contested Proto-Indo-European origin. But, hey! You can really say that the etymology of reggae is a real rags-to-riches story!

Qwerty is an official word in the English dictionary (though highest usage is still in all-caps), describing the most common kind of keyboard. The first modern typewriter was created in 1867, and it utilized the more obvious abcde format. But because often-used letter combinations like s and t punched in close succession would jam the typewriter, manufacturers had to think of a different combination. So in 1874, the qwerty variation was introduced, arranged so that there was more space between frequently-used keys. Then it stuck and nobody wanted to get rid of it. While we're talking about keys, this would be a good time to mention that the tab key is a shortening of tabulate key (for it was used to construct tables) and the shift key caused the typewriter carriage to change position. How antiquated.

This post was both requested and is highly interesting to me. As soon as the Bolsheviks took power, they began organizing labor camps as early as 1919. Once Lenin died and Stalin (whose name means steel) took power, he began to standardize the labor camps, setting up an administration to deal with it. This administration, formed in 1931, was called the glavnoe upravlenie ispravitelno-trudoykh lagerei, which meant "main administration of labor camps". Since that was a mouthful, they took those letters I bolded and abbreviated that mouthful to gulag. Soon, through metynomy, that administration's cool new name got applied to the camps themselves. Later on in the '70s, newly-McCarthyist Americans picked up the word to showboat the atrocities of the Communists, and that's how gulag entered US pop culture. Suprisingly, the stylization Gulag is much more prevalent than gulag or GULAG, and usage has plateaued recently.

|

AUTHORHello! I'm Adam Aleksic. I have a linguistics degree from Harvard University, where I co-founded the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society and wrote my thesis on Serbo-Croatian language policy. In addition to etymology, I also really enjoy traveling, trivia, philosophy, board games, conlanging, and art history.

Archives

December 2023

TAGS |