|

The word hippopotamus comes directly from its Latin cognate hippopotamus, which itself underwent very little alteration as we trace it back to the Ancient Greek word hippopotamos. This word is a combination of two previous Greek words: hippo, which meant "horse" and potamos, which meant "river". Therefore, a hippopotamus is the "horse of the river", which kind of makes sense. But technically the modern abbreviation hippo doesn't refer to the fat animal, etymologically speaking. Anyway, hippo comes from the Proto-Hellenic ikkwos, from Proto-Indo-European hekus, "swift". Potamus officially has an uncertain etymology but may come from the earlier word pipto, which meant "to fall" (since a river falls) and that would be from the Proto-Indo-European word peth, meaning "to fly", which also makes sense. Yay, fun!

0 Comments

There is a (probably) apocryphal story about the origins of the location name Yucatan, but it's worth telling anyway: when the Spanish conquistadors landed, they asked the natives "where are we?" but the natives, of course did not understand, so they said "yuca-hatlanas?" in reply, which really meant "what did you say?". The name then stuck. However, this account, first documented by Hernan Cortes, is probably wrong. If that is the case, we still have little clue what's going on: the word could be from the Mayan word yocatlan, which meant "place of richness", from the sentence u yu catan, "the necklaces of our wives", from the possible self-appellation of the Yokotan people, or even from a Mayan word meaning "massacre". In short, etymologists are befuddled. The only thing we know for sure is that it has Proto-Mayan origins (yes, that's its own language family. Oooh...). Oh well.

If you think about it, abject ("miserable"), object ("thing"), inject ("to push into"), deject, ("depress") and reject ("dismiss") all share the same Latin root: what went into English as ject came from Latin as the verb iacere, which meant "to throw". It all makes perfect sense if you think about it. Ab- means "away from" (from the PIE root apo, "away"), and something miserable is meant to be thrown away. The same logic applies for deject: de- (of Etruscan origin) means "down" and you can definitely makes someone depressed by throwing them down figuratively. Re- (from PIE wret, "to turn") means "back", and throwing something back is the ultimate sign of rejection. When you inject something, you're pushing it in (yes, in- the prefix, which derives from PIE en, means "in", obviously), and it's only a bit of a stretch to say you're almost "throwing" it in. Object is the strangest of the five and has developed the most: ob- (from PIE opi, "against") was the Latin prefix for "against". Something against which stuff is thrown is a target, and a "target" was exactly what the original definition for object was; later it developed to mean "stuff" in general and singular. Now that we know all that, iacere is from the Proto-Italic word jajko, from Proto-Indo-European hyeh. Both terms meant "to throw". How interwoven our language is!

The word hike has mysterious origins, but etymologists can definitely trace it back to the earlier English word hyke, or “to walk vigorously”. This term was first recorded in the dawn of the nineteenth century, but wasn’t commonly used until the dawn of the twentieth century. Beyond the origin of hyke, it’s hard for linguists to tell, but it may be connected to the Middle English word hicchen, or “to move” (also the root of hitch as in “a hobble”, which if true means that the phrase hitch hike actually means hike hike). This term is of equally obscure origin, which may not help us much. Both hitch and hike cannot be compared to other terms through philology, because of a lack of cognates. This suggests they might be connected, and with their semantic and phonemic correlations, it seems almost probable. This, however, is unproved and may be wishful thinking on my part, because I just want to say hike hike.

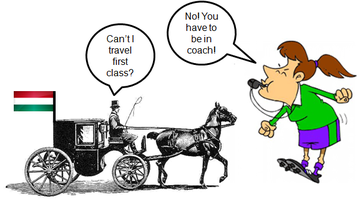

The word coach has two distinct meanings: “athletic trainer” and a “carriage” of some kind. The former meaning came along much more recently; it was coined by college students in the late nineteenth century as a metaphor for one who "carried" student athletes to success (so yes, the words are related). The "carriage" definition came into English in the sixteenth century from French coche, after which it followed an east-to-west, going backward to German kutsche and Hungarian kocsi. All the definitions of these words followed a semantic structure having to do with transportation, but that all changed with the etymon of kocsi. This word actually was named after the local village of Kocs, because in olden times they had many cart manufacturers down yonder, and metynomy worked its magic. Since the Kocs carts were so amazing, they also made a linguistic impact from Slavic to Romantic languages.

In the old voodoo religions of Western Africa, there was a snake god named the zombi. There was a general theme of similar words in the Bantu family; in various cultures, words emerged like zumbi ("fetish", the idol type), nzambi, ("god") and eventually zombie, still referring to the snake god. Later, when some of these Western Africans were taken to the Caribbean as slaves, they brought their language with them, and it mixed with Spanish and other tongues, especially in Haitian creole, where zombie ("god") and the Spanish word sombra ("ghost") kind of fused to form zombie ("ghost god", or, more accurately, "reanimated person", since they were basically synonymous). This idea of the dead rising from the grave was too tempting for Hollywood to pass up (it was first used in the 1932 film White Zombie), so the word wormed its way into our pop culture to be ingrained in the nightmares of children forever.

The word left, as in the direction, has a fascinating etymology. The farthest back we can trace it is to the Proto-Germanic term luft, which meant "worthless or weak" and may be from the Proto-Indo-European root laiwo, or "conspicuous". This later disintegrated into Old English as lyft (no, not the ride-hailing service), which still meant "weak". As the spelling changed to modern, so did the definition: since the left side is weaker on many people, the word left was used to describe that general direction. This next part is very interesting: the definition of left as describing liberals, Democrats, and socialists hails back to the days of the French revolution, where the reactionary and conservative nobles sat to the right side of the President in the National Assembly, leaving the liberal Jacobins and Montagnards to be seated on the left. This usage was later coined by a historian in the mid-nineteenth century, and has stuck since.

There are Francophiles and Anglophiles, but nobody takes culture appreciation to the extreme like Japanophiles do. This is why several slightly derogatory terms have emerged to describe people with such an interest in Japan that they experience a sort of cultural fugue, a split from their nation. The predominant slang for this kind of person is weeb. This is a corruption of the earlier, also-still-in-use term weeaboo. While the words sound like they have very Oriental origins, weeaboo in fact originated from a webcomic, The Perry Bible Fellowship by Nicholas Gurewitch. In the comic, the word was intended to be used just that one time and was actually stylized wee-a-boo, but it was quickly spread by 4chan boards (for the site was originally intended for Japanophiles), evolved into weeaboo and eventually weeb, and replaced the more derogatory term wapanese, a portmanteau of "white" and "Japanese". Since then, usage has exponentially increased, especially from 2014 to 2016, when the word seeped into mainstream culture.

The word unitard is a play on the word leotard, with the obvious substitution of the prefix uni- for (the not a prefix) leo-. But where does leotard come from? It was named after Jules Leotard, who popularized the skintight onepiece in the early 1800s. There have been several other people with the surname Leotard, but not enough to warrant any etymological information (there's no research on this). This means that, to fill the next half of this blog post, I'm going to have to make some crazy conjectures. Any French names probably trace back to either Germanic or Romantic languages (notable German or Latin). In Latin, the word leo means "lion" and tard in French also means "late". If we follow the Italic pathway, Leotard could mean "late lion". Another option is that liu, meaning "place" in French, and Thard, a place in France, were combined to denote that Jules' family was named after a location. However, there is also the Germanic option: surnames such as Lyotard and Liuthard exist, so that could be a pathway too. Don't take my word for it, though; I'm just theorizing here.

The word membrane hails from the Latin term membrana, which carried multiple meanings (including “membrane”, “skin”, and “parchment”). This is a conjugated form of the word membrum, which meant “limb” but literally carried the meaning of “a member of your body” (the word member is still used in this context in English, though not so much anymore) as well as being a euphemism for “male sex organ” (another slightly archaic though still used term). We actually got all these English terms from that word, through French membre, and the meaning “person in a group” after the body part definitions because it followed the concept of a part representing a whole. Anyway, the Latin word membrum most likely comes from the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European term mems, which meant "flesh" (though earlier on it may have meant something more like "meat". You can remember it this way: for any group, its members' members are made of meat.

Do the words hear and ear have the same root? Ear can be traced to the Old English term eare, from Proto-Germanic auso, from Proto-Indo-European hews. All this while the definition stayed the same, but here it might go back to the PIE term for "observe", keu, which may be related to the word for "to see", hew. It's complicated, to say the least. Hear only gets more complicated as we go back: it traces to Old English hieran (with variations including heren, heran, and hyran), which is reconstructed as deriving from the Proto-Germanic term hauzjan (still meaning "to hear"), from the Proto-Indo-European abomination of a reconstruction hkhowsyeti, which literally meant "sharp-eared". Drop the PIE word for "sharp", hek, and we roughly get hows, a word for "ear", and a suffix, yeti (not the monster). Hows connects to hews, and the rest is history. Literally. Interestingly enough, on a side note, the word ear as in ear of corn has different roots; it's from Old English aeher, from Proto-Germanic akhuz, from the Proto-Indo-European word ak, meaning "sharp".

The word opium at first glance seems exotic, with Afro-Asiatic or even Dravidian roots. However, when one analyzes the word closer, one notes the obvious Latin suffix -ium, as well as the endings -oid and -ate for opiod and opiate, respectively. Turns out that when I thought this I was correct, but how were the Romans connected to opium? They got it from the Greeks, who got it from the Persians, who got it from the Indians. The word can therefore follow that path as well: we know it's from Greek opion, "poppy juice". One theory traces this back to the Proto-Indo-European word swokos, meaning "juice". Other routes include origins from Turkish (as afyun, "opium"; this would have Persian roots) and Sanskrit. In any case, we can see an east-to-west diffusion of word and material, and this stuck in our language from Latin.

Technically, falls are the only real accidents. Collisions and mishaps? Forget those. The word accident entered English in the 1300s CE. This is from the 1100s CE Old French term accident, from Latin accidentem, or "misfortune". This is a conjugated form of accidens, which is a conjugated form of accidere, a word that meant "to fall on" or "fall out of". Now we can remove the obvious suffix ad (which means "toward" and is from Proto-Indo-European ad, "near" or "at"). The root of the word accidere is cadere, which meant "fall". This is from the hypothesized Proto-Italic word kado, from the even-more-hypothesized Proto-Indo-European term khd, also defined as "fall" with secondary definitions of "to make something fall" and "to lay out" (for those interested in the dialects of southwestern England, this is also the root of the Cornish word for "hail", keser). I wonder whether the origin of this word happened on purpose or by accident.

English speakers picked up the word monsoon (describing a period of rainy tropical winds) from Dutch speakers (who said monssoen), who picked it up from Portuguese speakers (who said moncao), who picked it up from Arab traders. These Arabic-speaking merchants used mawsim as a word for "seasons", since the monsoons marked the seasons pretty well. Since they marked the seasons, it then makes sense that the etymology would proceed back to the Arabic word for "mark", wasama. This is said to have origins in the root w-s-m, which if true probably means that it ultimately goes back to Proto-Semitic and the theorized Proto-Afroasiatic tongue. If this is not the case, the word may have origins in one of the Indian languages, but nothing is for sure. Surprisingly, usage is significantly higher for the word monsoon in Great Britain than in America.

Like the word Frisbee, the word for a granola came to us through a trademark. In 1886, Kellogg established the word as a proprietary name, which expired in the 1900s. When it was invented in 1863, the granola was actually written granula, but the famed cereal company switched things around slightly. Anyway, granula (and the similar word granular) obviously is an alteration of granules, which mean "small particles". Granule is from the Latin word granulum, a conjugated form of granum, which meant "grain" or "seed". This is from its Proto-Indo-European cognate and etymon, greno. We also get our current word grain from the Latin word granum, through Middle French grein and several alterations in Middle English that shifted from predominately greyn to predominately grayn and into our current form. Usage of the word grain is still more than a hundred times prevalent in literature than granola, which is also curious.

Approximately seven millennia ago, primitive peoples were using the holophrase pleu in the context of "to flow" or "to float". Since these Proto-Indo-European speakers somehow figured out that lungs float while other body parts do not, pleu was conjugated into the word pleumon, which meant "lung". This went into Greek as pneumon, which was later altered into pneumonia to describe "an inflammation of the lungs". Meanwhile, this pneumon became the Latin word pulmo, also meaning "lungs". This became pulmonarius, or "of the lungs". Through French, this then jumped the English Channel into English scientific jargon, where it took the form of pulmonary, a word which remains today (defined as "relating to the lungs") and precedes a laundry list of respiratory diseases. In retrospect, it's not that surprising to see these two words connect, but it's interesting to observe how they develop over time.

The symbol for zero, or 0, is from the Hindu numeral which looked just like it, which obviously conveys emptiness because of the perceived hole we see. The concept of zero also originated in India, as did the word for it. Etymologists know for sure we got it from Italian zero, since the Italians were first in contact with the Arabs who used the word sifr, which meant "zero" and is the etymon of the word cipher (which, for those of you who don't know, today means "code" but previously also meant "zero"), through Italian cifra and French cifre. Sifr, which also took on the meaning of "void" as it continued in Arabic, can be followed back to the earlier Arabic word safara, which meant "the quality of being empty" (curiously, the same character for this also represents the second month in the Muslim calendar). This in turn has origins in the Sanskrit word sunyas, defined along the lines of "empty".

Mammoth as an adjective for "huge" obviously was named after the extinct animal, but where did the name for mammoths originate? It didn't sound Indo-European, and the word fit into my schema for Quarternary period America, so I deduced Algonquian. How wrong I was. Turns out it isn't Indo-European, but it's as far as you can get from the Americas. Through Russian mammot, the noun mammoth traces to the Mansi (the Uralic language of an indigenous Siberian people) word menont, which meant "earth-horn". This is a portmanteau of the Mansi word ma ("earth") and ant ("horn"). Ma (with Finnish cognate maa, since Finnish is also Uralic) is from Proto-Uralic mexe, meaning "earth", which may actually be from Proto-Indo-European. Ant also has Proto-Uralic origins. The word mammoth entered English in 1706 and its usage spiked highest in 1878. The Russian word mammot was also used to create the genus classification of mammutidae.

Shakespeare may have invented the knock-knock joke. In Macbeth, a porter twice asked "knock, knock! Who's there?" in a manner very similar to the joke, which possibly sprouted off of that scene. The running joke may also have originated in medieval castles, where bored guards would goof around with people on the other side of the door. In any case, usage for such humor has shown to increase over time. The word knock can be traced to the Middle English word knokken, from the Old English word cnocian, or "to pound", which is of an onomatopoeic origin, unsurprisingly (though I dare you to knock your knuckles on anything and ask yourself if it really sounds like cnocian). Knock took on several sexual senses such as knocked up, knockers, and knockout because in the sixteenth century, knock took on a vulgar double definition as a euphemism for sex; it's easy to see why. This mostly faded out but its descendants remained. The silent k in knock is characteristic of Germanic words: it used to be pronounced KUH-nock, but that changed when people decided that that version was harder to pronounce than if the syllable was dropped altogether.

We've all done it. Stuck our fingers in our ears and yelled "la-la-la, I can't hear you" whenever a friend tried to spoil a movie or something. Turns out that this form of babble is universal, and definitely has some connotations in the world of linguistics, though we're not sure which. These kinds of sounds are called canonical babbling, and are imitative in nature, so there's no real etymology to it, but hear it gets interesting: In Sanskrit, lalalla was a form of making fun of stammering. In Greek, lalage means "to babble". The English word lullaby is from the Dutch word lullen, which is onomatopoeic for"mumbling or talking nonsense". In Latin, the word lallere also meant "lullaby" and also was probably onomatopoeic (and these lullaby words are characteristic of babbling, because when one is singing to a baby, one does not always adhere to linguistic structures). In Lithuanian, laluoti means "to stammer", and in German, lallen also means "to stammer". All these variations of la meaning similar things are indicative of a common language which precedes all others. Either that or it seconds Chomsky's theory of universal grammar. Man, we know very little about all this stuff, but it's fascinating.

When prescriptivists tell you that naive is exclusively spelled naïve, they are in fact wrong: the former has a much higher usage and is equally correct. The word naïve (which I'm spelling this way because it is so cool anyway) is a direct loanword from French, which goes back to the Old French term naif, or "innocent". This derives from the Latin word nativus, or "natural", since innocence is supposedly natural. The word may sound a bit familiar because it is also the direct root of the current word natives, the natural inhabitants of a place. Both of these words are from nascor, or "birth", since something present at birth is natural, and this is from the Proto-Italic term gnaskor ("to be born"), ultimately from Proto-Indo-European genh, or "to produce", which also had undertones of "birth". When conquistadors described New World natives as naïve, they had no clue how right they were, linguistically speaking.

Technically a "polar bear" would make more etymological sense if it was an "arctic bear". The word bear, meaning "a big carnivorous animal", comes from the Middle English term bere, from the Old English term bera, from the Proto-Germanic term bero. All of these end-vowel-switching words meant "bear", but their etymon, the Proto-Indo-European root bher, meant "brown", which proves that brown bears are also etymologically correct. But wait! People 8,000 years ago must have encountered bears too; why doesn't the current name stem from the PIE word for "bear" (which was hrtkos)? Well, the term mostly died out, to be replaced by this other, metynomic one, but it survived in Ancient Greek and Latin, as arktos and ursus, respectively. This former word was also later borrowed into Latin as arcticus, or "northern", since many bears lived in the north. Finally it went into English as arctic, with the definition we know today. How curious....

Almost everybody knows the story of how the frisbee came to be. Back in the 1930s, some New England college goofballs started tossing around upside down pie tins. One kind of these tins was manufactured by the Mrs. Frisbie's Pies company. Obviously, the name stuck. Eventually, big money realized that there was profit in selling such projectiles, notably a corporation called the Wham-O Company, which immediately slapped a trademark on its newly-popular product. Technically, the trademark remains to today, so the word Frisbee shouldn't be ubiquitous and should always be capitalized. Going backwards now, Frisbee is clearly a proper noun, one which has been present throughout basically all of English as we know it. The word can be followed back to an alteration of Frisby, a word to describe the Frisians, an ethnic group of people. This means the word is definitely Germanic (as the people are), and even more definitely Indo-European. What a bucket of giggles!

The word karaoke clearly doesn't seem like it has English origins; looking at it, it is obviously Japanese. Well, there are more layers than one would think. It's a double borrowing! Karaoke, or the singing pastime, was coined in 1979 as a portmanteau of kara ("empty") and oke ("orchestra"). It was named thus because in karaoke, one normally sings without accompaniment. Especially since I'm terrible at transliterating Oriental languages, I can't trace kara further, but it seems to have normal Proto-Japonic origins. However, oke is an abbreviation of okesutora (still meaning "orchestra") which was an honest-to-god plagiarism of the English word orchestra. This means that an English word was borrowed from a Japanese word which was borrowed from an English word! Wow. Anyway, the word orchestra used to refer to the space where the musicians played, and through Latin it derives from Greek orkhestra, or "a place where dancers perform", changing the meaning slightly. This is a conjugated form of orkheisthai, which meant "to dance". Going further back, this is a modified version of erkhomai ("to go"), from the Proto-Indo-European root for "to move", ergh. When people dance to karaoke, they have no clue how etymologically ironic that is.

While working on my eye infographic, I stumbled into the interesting question of whether the words pupil (meaning "student") and pupil (the part of the eye) are related. Turns out that the story is quite interesting. The first definition of pupil came from the French word pupille, which meant "orphan", since many orphans became students, supposedly? This is from its Latin etymon pupillus, with the same meaning. This is a diminutive of the earlier word pupus, or"boy". Pupil meaning "the part of the eye", however, derives from the French homonym of the previous word pupille, which in this case meant "little doll", so named because of the tiny reflections of people you see when looking into someone's pupil. This is from Latin pupa ("girl"), which, unsurprisingly, is the feminine form of the word pupus, "boy" (the word pupa, incidentally, is in English, meaning "maggot". This ties into my past infographics because that was coined by Linnaeus) . Now that we've joined the two words, pupus goes back to the Proto-Indo-European root pehw, meaning "little". How FASCINATING!

|

AUTHORHello! I'm Adam Aleksic. I have a linguistics degree from Harvard University, where I co-founded the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society and wrote my thesis on Serbo-Croatian language policy. In addition to etymology, I also really enjoy traveling, trivia, philosophy, board games, conlanging, and art history.

Archives

December 2023

TAGS |