|

Bleach can lead to temporary baldness if overused, but few people know that the connection between the two words is much stronger from an etymological perspective. The word bald came from Middle English ballede, which traces back to Old English and the word bala, or "white patch". This came from the Celtic bal, which meant "fire"; the transition occurred because of how shiny bald people's heads get; this in turn can be traced through Proto-Germanic balo "flame" and has the origin of the Proto-Indo-European word bhel, meaning "light" or "bright" (the qualities of a flame). Though Bhel is an etymon of a myriad of words like beluga, blitzkrieg, and blush, in this post it is most important in one of the paths it took into Proto-Germanic: that of blaikjan, or "to make white". Blaikjan disintegrated along with the tongue of the time, but squirmed its way into the dialect of Old English speakers as blaecan, "to whiten". This became Middle English bleche and eventually our word bleach, showing that not only does a cause and effect relationship exist between bleach and baldness, but an etymological one does too.

0 Comments

Most of you have no clue what the devil a zwischenzug is, but let me assure you that its etymology is oddly appropriate. As any devoted chess player can attest, a zwischenzug is a move where, instead of immediately executing an action, you interpose with another move. Like zugzwang, zwischenzug is brimming with unnecessary z's and, more importantly, comes from German. It is a combination of zwischen, "between", and zug, "move". Zwischen comes from Old German, where it used to be zuisken, which was a conjugated form of zuiski, "twofold". Zuiski came from the Old High German number zwene, or "two", which through Proto-Germanic traces back to the Proto-Indo-European word for "two", dwoh (also the etymon of English two). Zug also took the Germanic route, coming from Proto-Germanic teuhana, "to lead or pull"; quite a drastic change even among other etymologies here. This, like zugzwang, came from the PIE root dewk, "to lead". Therefore, the etymology of zwischenzug can be "two pulls", which is what you play out on the board.

The word mango hints at an exotic origin, and I first thought Africa when I came across it (silly me! So unknowledgeable about the history of the mango!). Turns out the word's history is closely correlated to the fruit's history. The mango first grew in South Asia, and was cultivated by Dravidian Ainu speakers, who called it ma kay, which roughly meant "an uncultivated fruit". This word passed into the Tamil language (arguably the most important Dravidian tongue) as mankay, still with the same definition. In the fifteenth century, Malay sailors dominated the Indian Ocean, trading from the South China sea to the shores of the Arabian peninsula. Therefore, mankay passed into the Malay language as mangga, quite a mangling, but they didn't care, since they were enjoying their mangoes. In the sixteenth century, Portugese sailors were the first to trade with Southeast Asia, where they picked up the mango and the local word for it, changing it slightly to manga. This soon spread to England as an intriguing exotic fruit with an intriguing exotic name: the mango.

Daisy has changed a lot over time, but its original pronunciation was by far the best. In literature, daisy has been corrupted a tremendous amount. In Modern English, it also used to be spelled daisie and daysie. Going backwards, the latter is perhaps more appropriate, because in Middle English, daisy was spelled several ways, including daysie, daieseyghe, and dayseye. The reason this changed so much over time is because nobody could agree on the proper spelling. However, when traced further back to Old English, the spelling was uniform (daeges eage), mainly because there weren't many people writing back then. You may have noticed a pattern to the pronunciations by now: they all sound like day's eye. In fact, that is what it used to be! Daisy, though it's hard to guess now, is a combination of the Old English words daeges, "day's", and eage, "eye". It was named thus because the petals open at dawn and close at dusk (similarly, in Latin it was solis oculus, or "sun's eye"; this likely had an influence on daeges eage). Daisy as a woman's name was apparently a nickname for Margaret (and today is as appropriate as Peggy).

People in finance refer to a mogul as a very rich businessman. People who ski call moguls those little snow-packed bumps you're supposed to shred between. Since these both refer to elevation, they should be etymologically connected, right? Wrong. These are homonyms coming from completely different sources. First, let's take a look at mogul, "the wealthy person". This is a direct borrowing from the Arabic word mughal and meant "Mongol" (as in Genghis Khan). This comes from a Mongol self-appellation, which further came from their word mong, or brave. As the Mogul people lost their first two empires, they settled down in India, where they made obscene amounts of wealth trading the valuables there. But what about the other mogul, the "ski bump"? This came from the German word mugel, meaning "a heap or mound". This came from Middle High German mugel, which referred to smaller things, like "lump" or "clod". Though the etymology on this is scarce, the snow mogul probably derives from Proto-Germanic, based on similar words in other Germanic languages. Anyway, the point of all this is, never judge a (book/bump/businessman, pick one) by its cover.

It seems so obvious in retrospect that algebra is Arabic! Like hazard, its structure is very distinguishable from Indo-European languages in the bizarre use of consonants and a favoring of the letter a. This discovery lead me further, to the origin of algorithm. Perhaps it is fitting to start with the latter. Algorithm comes from French algorithme, meaning "system of computation". This came from the earlier French word algorisme, which derived from Latin algorismus "an Arabic numeral system". Algorismus is a corrupted translation of a man's name, Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi. If you take a closer look at al-Khwarizmi, you can note the similarities with algorithm. But who is this Khwarizmi chap anyway? The man who invented algebra! Back in the ninth century, al-Khwarizmi created a new form of mathematics, and named it al-jabr, or "reunion of broken parts" (describing how you solve the equations). Best as I can tell, jabr goes back to the Semitic root j-b-r (keep in mind there were no vowels), probably meaning "broken" as in bones, though uncertain. In any case, al-Khwarizmi's word weaseled its way into Latin as algebra, which found its way here today. It's fascinating how algebra sprung from an algorithm! Etymology is AMAZING!

Etymologically speaking, when you refer to your "maternal uncle" you are really saying my "mother's mother's brother" or even "mother's grandfather". Uncle comes from French and the curiously spelled word oncle, which traces further back to Latin. Here it was avunculus, which only referred to what we today call a maternal uncle. This is also the direct root of the word avuncular, which means "of, or relating to, an uncle". This is a conjugated form of the word avus, which meant "grandfather". This, like much of Latin, goes back to Proto-Indo-European, in this case to the word awo, meaning "grandfather". Going further back, this reconstructed word meant "any non-paternal relative". As a native Serbian speaker, I know Serbs say ujak for uncle, and I was unsurprised to learn that this too traces back to awo. Similarly, I was tickled about the change in generation, from "grandpa" to "uncle". Maybe someday "uncle" will mean "nephew"!

To eat humble pie is to admit one's mistakes, to be embarrassed for one's actions. So, consequentially, it comes from the word humble, meaning "modest", right? Wrong. Humble as in humble pie has quite different origins. Tracing back to the Proto-Indo-European word lendh, meaning "loin of meat". Passing through Proto-Italic as londwos, this became lumbus in Latin, still meaning "loin". This was conjugated into lumulus, which had a heavy influence on the development of the French word nombles, specifically referring to "beef, veal, or venison". Since French people really don't put enough stress on their first syllables like us Germanic speakers, the n- got dropped in favor of the new word umble, pertaining to the undesirable parts on the inside of an animal. Since nobody liked eating umbles, but poor people had to, eating umble pie became a term meaning that you have a modest background. Eventually some prankster in the nineteenth century decided to make a pun about umble pie. The whole phrase described a humble background, and umble sounds like humble, so why not add an h-? Thus we get our term humble pie, which etymologically speaking should be numble pie.

The etymology of obsession is curiously appropriate. Back in the early days of the English language, it meant "besiege", firmly reinforcing today's stalker connotations (though it also went through a brief period with supernatural connotations). This came from the French word obsession, which came from the Latin word obsessio, "a blockade". In this you can see the metynomical transition from a noun to a verb, which is quite fascinating. Anyway, obsessio is a conjugated form of the word obsidere, which is a portmanteau of the prefix ob- "against" and the root sedere "sit". This makes etymological sense since one would sit against a blockade to reinforce it. Ob- came from the PIE root opi, which doubled as "near" and "against". Sedere can also be followed back to Proto-Indo-European, in this case the word sed (which may be familiar from my post about cathedral). Thus, an obsession is to "sit nearby" your prey, a very stalker-y word back then as today.

Drugs can often be associated with abnormal psychological behaviors, but this is etymologically correlated in the word narcissism. Looking at it, you can extrapolate the prefix narc- (as in narcotics) but how far does this origin go? Narcissism has mythological origins, and was named after the man who fell in love with his own reflection, Narcissus. This came from Greek narkissos, which was a type of flower, presumably a lily. Narcotics come from the French term narcotique, which came from Latin narcoticum, which came from Greek narkotikon, which can be traced back to the Greek word for "numbness", narke. When etymologists compare narkissos with narke, there is a clear connection, especially when one considers that early drugs came from flowers. While this might come from the PIE root nerq, "to twist", this is doubtful and these probably trace back to the severely unexplored proto-Mediterranean language linguists know so little about. My guess would be something like nerk, which would probably be connected to the PIE word. We'll never know for sure, until time travel is invented, but in the meantime, if you're a narcissist, stay off the narcotics.

If you wear leather to a movie, you have no idea how etymologically appropriate that is. Turns out the word film has skin-centered origins, starting with its original definition, "to cover with a film or thick skin". This was an important process in the makings of early films, so the name stuck. Going back further, the earlier verb film comes from Old English, where the word filmen meant "membrane or skin". The etymon of this curious word is the convoluted West Germanic term filminjan. This traces back to the Proto-Germanic word filminja (these last two both still meant "membrane or skin". which probably comes from Proto-Indo-European and the reconstructed word pel, meaning "animal skin or hide". The older, non-movie sense of the word film is still present in the English language, now referring to what is normally a thin strip of plastic. They should make a film about this...

Today we swear in our new president, and this word seems appropriate. Looking at the word inaugurate, you can clearly pick out the word augur, which, as fans of Roman mythology can attest, is a guy who sees the future. So how did this arise? To find the answer, the etymology of inauguration can be traced all the way back to Proto-Indo-European and the root aug, or "to increase" (also present in augment and in auxiliary, as in "Trump's inauguration augmented his auxiliary"). The PIE root aug faded along with the language, but showed up in Latin as the word augos, with the same definition. The history at this point was messy, and probably a word halfway between augos and augur showed up, meaning "to increase crop yield by ritual". Then the Latin word augur finally showed up. This, in its conjugated form augurare, got prefixed with in- to make inaugurare, or "to consecrate, if the omens were favorable". This definition might sound weird, but the Romans were very superstitious people and would only promote a dude to centurion or whatnot if there were good vibes. Far out! Anyway, this became inaugurationem, which just meant regular old "consecration", which passed into French then English as inauguration. It's sort of fitting that something bound to enlarge one's ego has the roots meaning "enlarge", but for an unrelated etymological reason.

I've been through the region, and there's no English word Serbians are more proud of than vampire. This word for "mythical person biter" apparently was first mentioned in the eighteenth century (much earlier that Bram Stoker's nineteenth century Dracula masterpiece). In one exclusive instance in 1732, the word "vampire" was used, as from German vampir. However, this was isolated and most uses of vampire can be traced to the French word vampire, which derives from Hungarian (a non-IE language!), and the word vampir. This traces through Serbo-Croatian, where the same word had the same definition. This in turn can be followed even further back to Slavic upir, still with the same definition. Where this comes from is a source of much controversy. The natural intuition would be all the way back to Proto-Indo-European, since Slavic is an IE language, but the sound styles don't really match up. This has lead linguists to debate endlessly over vampire, with some factions claiming that it has origins in Macedonian and others claiming that it comes from Tatar ubyr "witch", though that is disputed. Another group claims that it's from Turkic, through Proto-Slavic. A lot of speculating about an imaginary creature!

The verb skiing comes from the verb ski, which comes from the noun ski, "the thing you ski on". Since skiing started in Scandinavia in seventeenth century, it makes perfect sense that the word comes from the same time and place as well. Ski came from its Norwegian counterpart, ski, which came from the earlier Norwegian word skith, "snowshoe or ski" (this was metynomically applied to the verb later). Going back even further in time, skith meant "a piece of long wood", because that's really all skis were. This in turn can be followed all the way back to Proto-Germanic and the word skida, which either also meant "wood", or more interestingly, "to cut or split" (as in wood). In any case, this can further be reconstructed to the Proto-Indo-European word for "cut" and "split", skei (also the root of the verb shed as in "molt" but not "building", and schizo-, but I'll save that for a future post). The point is, it's curious how words can splinter over time, isn't it?

The word hair kind of makes etymological sense for some people, but with others not so much. In the primordial English language, when words were so garbled you probably couldn't recognize them, it passed into our language, but the sounds changed a lot. for a while, hair was spelled alternatively as her, heer, and haer before people finally settled on a standardization. This is curious but not extraordinary; this was a very tumultuous time in the English language. When first asked about this word, I guessed based on the hard consonant ending that it was Germanic, but the soft h at the start confused me. Turns out this is rightfully so; back in Proto-Germanic from whence this term came, the word khaeran was utilized, with the current definition. This beginning was kind of guttural and faded over time. Khaeran in turn came from Proto-Indo-European and the word ghers, which meant "to stand out" or "bristle". This is also the root of today's word horror, because of the way you bristle with fear when you're scared. Next time you see someone with wavy hair, tell them they're etymologically incorrect, gosh darn it!

I thought I would change things up a little; this is the first word on my blog not to come from Afro-Eurasia. The word igloo, meaning "a domed hut made out of ice", can be traced back to a word in Proto-Eskimo (not to be derogatory; that's the language's name) which vaguely sounded something like uhnloo and, based on the evidence I could find, arose just as the First Nations people both were beginning to use language and inventing igloos; around 4000-5000 BCE. Obviously, Inuit natives had no written languages, and much like with Proto-Indo-European, etymologists had to make an educated reconstruction of the word based on phonetic frameworks. As far as we can tell, this later passed into Proto-Inuit with a word that sounded like ugloo, which had descendants in nearly all northern-North American native languages as far as anyone can tell, and meant "any kind of house or building", since that's all the Alaska natives had to live in. This went into Inuktitut as igloo, and later got picked up by both Canadian English and French explorers. The American word igloo comes from Canadian, and many other European countries, like the Netherlands, Poland, and Serbia, all have their word for igloo deriving from the American English version.

A croissant is quite aptly named. The English and French word can be traced further back to an earlier French word, cressaunt. This is fascinating because it is also the root of the word crescent; croissants were named thus because of their resemblance to a crescent. Both have agricultural origins, but not directly so. Cressaunt came from the earlier term creissant, specifically referring to the "crescent of the moon". This came from a Latin word, which probably was either crescentum, crescens, crescere, or cresco, all of which had to do with "thriving" and growing out of the ground (and the etymon of create). This change is weird, and kind of hard to understand, but I'm sure it makes sense to those superior to you or myself in etymology. Crescere and all its forms are derived from Proto-Indo-European, and the root ker, or "to grow" (for fans of mythology, that's the root of the goddess Ceres). People like colloquialisms about things growing on trees, and next time somebody asks you if money grows on trees, you can simply ask, "Etymologically speaking, croissants do. Why not money?" You're welcome.

I was shocked to find that the word ebony (describing a specific kind of dark wood, but colloquially synonymous with "black") does not have Indo-European origins. The closest relative to this now-English word is ebon, which was present in Middle English and only pertained to the tree. This is actually a misspelled word from Latin; some asinine "scholar" somewhere totally butchered the word hebeninus, which is what the Romans used to talk about anything concerning the ebony wood. This probably came from a much earlier Greek word, ebininos, itself stemming from ebenos, with the aforementioned definition. This is curious because the mistake by the scholar actually comes closer to the Greek word than the Latin one. We are, however, going to add the letter h one more time, while going back even further... to Egyptian! I couldn't find any dates on when this transition happened, but the Greeks and Egyptians interacted a lot (especially due to Alexander the Great), so once you get over the initial etymological surprise, it kind of makes sense. Anyway, in Egyptian the word was something like hbny or hbnj (no vowels). This probably has some kind of Semitic origin, but nobody's exactly sure what.

The great psychologist Sigmund Freud would have been extremely satisfied with the origin of the word felicity, if he ever found out. This word for "happiness" can actually be traced all the way back to the Proto-Indo-European word dhe, "to suck, suckle, produce or yield". You can clearly see the... maternal origins of the word, which may be etymological proof of the Oedipus Complex. In any case, dhe lead to Latin (as many of our words seem to), and the word Felix, which like Felicity is a rather lucky name (its definition is "luck", though it doubled as "fertile" in the early times). This gave way to felicitas, or "lucky", which hung around a bit until it got picked up by the French, who used the word felicite, meaning "happy", since those who are lucky are normally happy. It took only a small hop over the Channel to become felicity, but that isn't nearly the most fascinating part of this serendipitous word. The best part is how this reflects on the human psyche, how someone somewhere equated true luck to being able to suckle milk as a baby. This is how etymology happens.

The verb to quarantine comes from the noun quarantine, but where does the noun come from? Turns out it can be traced all the way back to the Proto-Indo-European word for "four", kweter. This is the root of the word "four" in basically every Indo-European language, from Slavic to Sanskrit, the commonality of which is remarkable because of its infrequence. Anyway, kweter disintigrated along with PIE, and one of its remnants dragged itself into Latin quattor, still meaning "four" (another descendant was the Proto-Germanic word fedwor, which led to today's fewer). This fed into the later Latin word quadraginta, or "forty". This happily existed along until medieval scholars in the sixteenth century turned everything upside down. Being very religious, they wanted to give a Latin name to the desert that Jesus fasted in for forty days, so they decided to be completly unoriginal and just call the desert "forty". This resulted in a corruption of the Latin word and the new word, quarentyne. This obviously gave way to quarantine, and explains the etymological connection between that and, say, quarter or Spanish quarenta. Other sources will tell you that a quarantine is the amount of time sick sailors had to be isolated from society; while this may be true, it is not the origin of that.

Penthouse may not have the origin you may think. If you try and break down the word, it appears obvious that this is a combination of pent- "fifth" and house as in "habitation unit". This, however, is about as far from the truth as you can get. Penthouse actually came from the Middle English word pentice, meaning "a kind of building". Through Anglo-Norman and French, this came through the Latin word appendicium, which meant "an attachment". This in term derives from an earlier Latin word, appendere, or "to hang". Appendere is a portmanteau of ad- "toward" (though the d got dropped) and pendere, meaning "to hang". This dates back a few thousand years more to the Proto-Indo-European language, where the root spen was in use, defined as "pull or stretch". If this sounds familiar, it's also the etymon of today's word span and pendant (the latter through the aforementioned Latin root). The reason pentice changed to penthouse is that medieval people looked at pentices and realized that "this looks like a house" so maybe they should correct an obvious error and name it penthouse. This kind of transition is called folk etymology, and this particular word is also rather well detailed in Anatoly Lieberman's Etymology for Everyone: Word Origins and How We Know Them.

Cholesterol is an organic molecule which nobody is fond of. Too much is bad, too little annoying. However, the etymology of it is definitely something to appreciate. My sources agree that it comes from French, but vary on exactly what word it was. One larger faction claims that it can be traced to cholesterin, from the earlier word cholestrine. However, two of my resources affirm that it derives from its cognate cholesterol. In any case, this linguistic confusion is pointless, since both (French) variations come from Greek, and the portmanteau kholesteros, or "stiff bile". This is a combination first incorporating the word khole, meaning "bile". This derives from kholoazein, or "green" (since bile is sometimes greenish), which came from kholoros "pale green", possibly coming from a Proto-Indo-European term meaning "shout". Khole also is the etymon of "cholera" and the name "Chloe", not to offend anyone. The second part of the aforementioned Greek word is stereos, which meant "firm". This can be followed back to PIE as well, and the root ster, which is the forefather of "sterility" and meant "strong, firm, or stiff". Now you can see that cholesterol once meant "stiff bile", you can go back to loathing it with reinforced hate!

The word hazard has a curious moral origin. Turns out that the farthest the word can be traced is to the Arabic term al-zhar (or az-zhar), which translated as "the dice". As Arabic dice games spread throughout the European continent, so did the word, and soon all those medieval people were playing al-zhar games. By the time the word migrated across all of Europe, it got twisted around, so it landed in Spain as azar. Here the word split into several definitions. One meant the game that was played, one referred to the random results of a dice throw, one referenced the positive, "lucky" results of a dice throw, and one the "unlucky" or "risky" dice throw. Naturally, all these conflicting definitions were confusing, so the Spanish kept the middle two, dropped the first word, and gave the last one to the French, who picked it up as hasard (those silly French! They add an h- and a -d and still can't make heads nor tails of their words). This originally pertained to unlucky dice throws, then was metaphorically extended to unlucky risks in life, then the latter was dropped, leaving only a "risky life decision". This was not much of a change as hasard became the English word hazard. Hazard was originally just a noun, but later it became a verb as well. Maybe someday we'll drop the noun, If I were to hazard a guess...

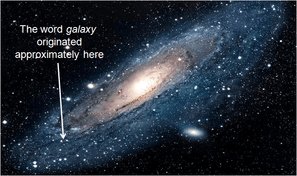

Both etymologically and scientifically speaking, there used to be a lot less galaxies than there are today. Though the scientific explanation is fun too, let's delve into the word origin: it can be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European word glakt, which is reconstructed meaning "milk". This may sound familiar, since its root went into Latin as lac-, which is present in lactose and lactate and a bunch of milk-related terms. But how does this connect to galaxy? Well, glakt went into Greek as galaktos, and then just gala, both still meaning "milk". However, this changed, since the Greeks were avid astronomers, and liked to name things up there in the heavens. Thus, the "Milky Way" became known as the galaxias kyklos, or "milky circle" (Milky Way itself is a translation of a Latin term deriving from this). Eventually people dropped the unnecessary "circle" part, but this still referred exclusively to our galaxy (because for all we knew back then, it was the only one). This then passed through Latin and French to enter English, and later became an official astronomer's term for a large collection of solar systems bound together by gravity. The "Milky Way" definition is only remembered by the heavens.

Paris. Somehow everybody wants to go there. This famed "City of Lights" may not be as... clean as people may think. The word for the city can be traced farthest back to the Proto-Indo-European word leu, meaning "dirt". This later became lhuto, still meaning "dirt", and then dawdled around in Proto-Italic for a bit (hiding under the pseudonyms luto and lustro). Eventually history went ahead and grew up a few thousand years, and the word found its way into Latin as lutum, "dirt, mud, or clay". Subsequent to this came the Latin word Lutetia, meaning "swamp", a reasonable transition from "mud" (Note: one of my sources says this whole explanation is a bunch of armadillo dung, and the word actually came from Gaulish). When the Romans went and conquered Paris in 52 BCE, they named it Lutetia Parisorum, or "swamp of the Parisii tribe" (which probably got its name from Celtic). Eventually, as the Romans left the area, people decided that was a mouthful, so they dropped the Lutetia and the -orum, leaving us with just part of an adjective that used to belong to a larger whole. So forget the "City of Lights", and visit the "dirty tribal town"!

|

AUTHORHello! I'm Adam Aleksic. I have a linguistics degree from Harvard University, where I co-founded the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society and wrote my thesis on Serbo-Croatian language policy. In addition to etymology, I also really enjoy traveling, trivia, philosophy, board games, conlanging, and art history.

Archives

December 2023

TAGS |