|

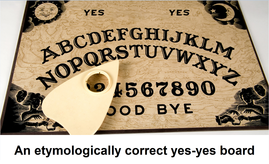

Most of us know of the Ouija game, that macabre activity where children supposedly communicate with the dead. Annoyingly pronounced "wee-jee", it is actually a trademark of Hasbro, and it has a glaringly obvious etymology I never realized until now. Two words constitute it: oui, the French word for "yes", and ja, the German word for "yes". In effect, the Ouija board actually translate to a "yes-yes" board. This is possibly because of the "yes" tile on the board, or simply because it sounds mystical. Anyway, French oui is from Old French oil (pronounced oy-eel), which in turn is probably a mush of the Latin phrase hoc ille, meaning "so he" literally, but "yes" figuratively. Ja had no change through Middle German, Old High German, and Proto-Germanic, but in Proto-Indo-European it was ye, meaning "already". Of course, this is connected to our word "yes". There are other theories as to the origin of Ouija, such as that the inventors of the board first spelled out that word, and that it's Egyptian for "good luck", but those hypotheses are unfounded.

0 Comments

I like to call my site a lexophile's sanctum. The first word is archaic and most dictionaries deny its existence, but it means "word lover" and sounds much better than logophile, in my opinion. The second word is commonly known, meaning a private or sacred place. As you can guess from the title, and length of this blog post, there are a whole lot of words connected to it. Sanctum has one of the simplest origins: it comes from Latin sanctus, meaning "holy", a conjugation of the root sancire, "to consecrate" (declaring something holy), which in turn derives from the Proto-Indo-European root sehk, with the same definition. Now, one of the first things you may have thought about is how similar the word sanctum is to the word sanctuary. This is not without a good reason; they are each other's closest relatives, perhaps, with sanctuary coming to us from the root sanctus as well (through Latin sanctuariam, "shrine", then Old French saintuaire). Additionally from sanctus, there is the word saint, which took the route of the Old French word seinte. Now we move back to the earlier Latin root and predecessor of sanctus, sancire, which, as a reminder, meant "consecrate". This gave us the word sanction (through Latin sanctionem), because the meaning of a "holy decree" got shifted over time to a "legal decree". Finally, the remaining relatives of sanctum can be found branching off from PIE sehk, through Latin: the words sacred and sacrament come to us through Latin sacer, which also meant "holy" (through Old French sacrer and sacrament, respectively; the latter also had a meaning of "mysterious" for a while). Also related are terms like sacrifice, sacrilege, sacristy, sacrosanct, Sacramento, sacrum, sanctitude, and sanctimony, but, quite honestly, I've proven my point that Latin holiness has pervaded our culture, they would take too long to explain, and I need to save something for future blog posts!

You can be raring to go, enjoy your meat rare, or have a rare crustacean collection. Is there a common root, or do they all have their own rare origins? Ironically, the latter. First, the one with a definition of "scarce": it comes from the Old French word rere, with the same meaning, from Latin rarus, meaning "spaced apart", since things that are spaced apart are rarer than those that are not, and that in turn is from Proto-Indo-European ere, which could have meant something like "separate" or "thin"- two definitions that can easily be connected to the prior meaning. Now onto the origins of your rare meat: the word is from Old English hrere, "lightly cooked", from hreran, "to agitate" (probably something to do with the cooking process). Prior to that, we can reconstruct it to Proto-Germanic hrorjan, "stir", and ultimately to PIE kera, "to mix". Last but not least, the word raring is an archaic form of rare, a dialectical way to say rear, the verb meaning "to raise", as in what you hopefully do to your child. Rear, through Old English and Proto-Germanic synonyms raeran and raizijana, originated from the Proto-Indo-European hrey, which meant something more like "to rise" than "to raise". Just thought that was whimsical and interesting...

The noun addict comes from the verb addict, and the verb addict used to mean "to devote", which is interesting but not that strange. This meaning also carried a connotation of "to give oneself over to", which is important as we move back to Latin addictus, meaning "surrender" (or still "devote"). Prisoners of war surrender, and surrendered POWs in Roman times became slaves, so addictus also carried the meaning of "slave" for a while! Before this, we can clearly break up addict into ad-, the prefix for "towards", and dicere, which meant "to say or declare", as in "to declare devotion", supposedly. Dicere, through Proto-Italic deiko, comes from the Proto-Indo-European root deykti, meaning "to point". Ad- merely comes from PIE ad, with more of a meaning of "near". So, throughout history, addiction has had definitions of "devotion", "slavery", "towards declarations" and "pointing near". I'm so addicted to etymology!

We call the country of the Finns Finland, but they call it Suomi. What's curious here is that neither of those words has a certain origin- both of their etymologies are obscure. The Fin- part of Finland apparently derives from the Old Norse appellation finnr, with an older meaning of something like "dwarf", but that's all we know about that. As for suomi, it's been theorized to come from Proto-Balto-Slavic zeme, meaning "ground", but that's uncertain, since Finnish is a Uralic language. Another possible explanation brings it back to Proto-Indo-European dheghom, or "earth", but this is a mere reconstruction and it's probable that never existed as a word at all. As word origins in European languages go, both of these are suspiciously lacking in substance. The gist of it all is that the origins of the Finns escapes us, in both their language and ours. Does this indicate that Finland doesn't actually exist? It's up to YOU to decide.

Today, foreigners call anybody living in the U.S. a Yankee. During the Civil War, it was specifically people in the Northeast who received that appellation, and in the early eighteenth century it referred to anybody living in Connecticut. Through all this time, it always had an underlying pejorative sense. This is all because of the Dutch influence in the New York colony, back when it was under their control, as New Netherlands: seeing the English, Puritan colonists as awfully boring and plain, they called them by a generic name: Jan Kaas, or "John Cheese". A fantastic insult for an American, no? It was meant to sound generic, and it accomplished that beautifully. Jan is a Biblical name: through Greek and then Latin Ionannes, it derives from the Hebrew name Yohanan, which probably means something like "God is gracious". Kaas, through Latin caseus, then Proto-Germanic caseus, originates from the Proto-Indo-European root kwat, meaning "to ferment". So, ultimately, Yankee means "God is gracious ferment". Yay!

I just got a very interesting question submitted: why is the plural of ox not oxes, but oxen (as contrasted to examples such as foxes, boxes, or poxes)? There are a couple other surviving -en words, like children, as the submitter pointed out, but for the most part our plurals are with an s. The reason lies in the competing influences from Anglo-Saxon and Proto-Germanic in the Middle English language. The Romantic, French, Anglo-Saxon plural was to add on an s, and the Germanic way was to add an n onto the ends of words. For a time, these suffixes coexisted peacefully, but eventually the s ending began to be more fashionable, and almost every word used it. However, language isn't uniform, and that's how we got these aberrations. It also helps that, in Old English, ox was spelled oxa, and it simply sounded better to keep on the n from the previous Proto-Germanic word ukhson (ultimately from Proto-Indo-Europan uksen, meaning "any male animal" in general)

The etymology of the word merry underwent a myriad of changes in Middle and Old English, undergoing alterations such as merrie, mery, merie, mirie, myrie, murie, merige, myrige, mirige, myrege, and... you get the idea. Clearly the word was used a lot back then; indeed, N-grams show it being most commonly used in the 1600s. Anyway, through all this time, it still meant "jolly" or "pleasant", but as we move further back to the reconstructed Proto-Germanic root murguz, it meant something more like "brief" or "short". This transition highlights the quality of happy moments to be fleeting, or of merry moments to be short. The final root to be reconstructed is that of the Proto-Indo-European mreg, meaning "short", the root of words from brevity to mirth. Going further back than that is impossible, but on a more recent and unsurprising note, Google search interest for the word "merry" skyrockets every December.

What, exactly, is the yule in yuletide? Or the tide, for that matter? Both are Germanic. Yule was actually the pagan holiday which was the precursor to Christmas, generally occurring around December. In Old English, it was spelled geol or geola and purportedly comes from the Proto-Germanic word jehwla, meaning "festivity". This in turn is from Proto-Indo-European yekuh, "to play". Meanwhile, tide is the same one that rolls in twice a day. That's just it: the tide occurs at a specific time, so in Old English it was tid, meaning "tide" or "season". This, through Proto-Germanic tidiz, came from the Proto-Indo-European root di, meaning "time", so yuletide technically means "play-time". Search interest. Google search interest for the word yuletide is most popular in Ghana, always peaks sharply every December, and pales in comparison to the word Christmas. Oddly, usage of Yuletide has been increasing since the 1980s.

The capital of Tajikistan (the greatest former SSR) is Dushanbe, a proper noun with a fascinating etymology. In the Tajik language, dushanbe means "Monday". This is because the village was right on the Silk Road and would have a huge and opulent bazaar every Monday, so that key facet became its name. Interestingly, dushanbe is a portmanteau of two Tajik words, do, meaning "two", and Shanbe, "Saturday". Monday was two days after Saturday, so the city named after Monday is in fact a couple days premature. Both components either are from or have cognates in Persian, which would make this Indo-Iranian and thus probably from Proto-Indo-European. Fun fact: from 1921 to 1961, Dushanbe went under the name Stalinabad, the time when it underwent its greatest expansion from the village to the glorious capital it is today.

The word dollar has quite the unexpected origin. The US dollar was inspired by the Spanish dollar (which came before both the pesesta and the Euro), a stable and highly valued currency around the time America formed; the founding fathers wanted to associate American money with something else that was valuable. This is an Anglicization of a German word which sounded something like thaler or taler, also meaning "dollar", and this is where things get crazy. Thaler is a shortening of Joachimsthaler, the name of a German town where much silver was minted. This in turn was likely named after some St. Joachim or other, but we're not too sure. Going back to the pesesta briefly alluded to before, it was abbreviated ps back in the day, when the two letters combined to create the dollar sign ($) that we know today. Spanish seems to have made a surprisingly large impact on our economy.

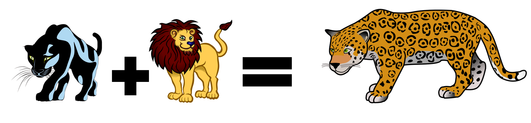

A leopard is literally a "lion-panther". In ancient times, the animal was thought to be a hybrid of the species, a middle ground, and so the people back then named it thus. As we move backwards, in Middle English, it underwent alterations such as lubard, lybard, libbard, and lebard (these variations we've seen so much are due to decentralization and lack of standards back then), from a similar myriad of Old French phonemic jumbles. Ironically, the Latin root, lepardus, is closer to the modern word than most of the changes. That in turn is from Ancient Greek lepardos, and since they were the ones who named the animal, they got to combine their words leon, "lion", and pardos, "panther". Both words are unknown in origin, with leon possibly not even having IE roots, and pardos potentially having a cognate in Sanskrit pradukh, meaning "tiger". Lions and tigers and leopards, oh my!

In linguistics, philology is the cross-referencing of texts, usually to reconstruct words or understand something about olden times. The etymology of philology was therefore discovered through philology, so let's dive in. This is not your usual -ology word; it's a portmanteau of philos, meaning "loving", and logos, meaning "words". A philologist loves words. Like a lexophile or logophile, but cooler, since it's an actual occupation. Philos has an obscure origin, but possibly comes from a Proto-Indo-European root sounding like bhil and meaning "good". Meanwhile, logos (the same as the rhetorical appeal) is from lego, meaning "say", from the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European root leg, meaning "to collect" (as in to get your speech together, apparently). Guess how that root was reconstructed? Philology!

The word squirrel is probably most interesting because of the sheer heterography in its past. In Middle English, it altered between squyrelle and squirel, and before that, it was spelled esquirel in Anglo-Norman, from French escurel. Note how both the q and the double rs were dropped by here. In Latin, it underwent variations such as scuriolus and scurius, and through sciurus, it ultimately derives from the Ancient Greek term skiourous, which still meant "squirrel" figuratively, but literally meant "shadow-tailed". This is because it is a portmanteau of two words: skia, meaning "shadow", and oura, meaning "tail". The former is from Proto-Indo-European skeh, also meaning "shadow", and the latter is from Proto-Indo-European ors, meaning "backside" or "buttock", even. Not too much semantic change in that word, but it's notable nonetheless; all words matter!

Today, let's have a brief, philologically unserious discussion on the origins of two Reconstruction-era terms, carpetbagger and scalawag. A carpetbagger was a person from the North who came down to the South to profit or make political gains after the Civil War, and the origin of that word is obviously a combination of carpet and bag, denoting the quality of these exploiters to travel literally with their carpets carrying all their other belongings, like a bag. Meanwhile, the word scalawag meant a Southerner who supported Republican (Northern) policymaking during the aftermath of the Civil War. This comes from a previous meaning of "worthless animal" (obviously it was pejorative), which might be named after the village of Scalloway in the Shetland islands, famed for its miniature horses. Today, both words have evolved, so this offers us an interesting snapshot into contemporary etymology: carpetbagger is a term for a politician who seeks election where they're not affiliated, and a scalawag means "naughty person", showing the pervading Confederate jargon employed today.

Hitler would have been greatly offended if you called him a Nazi. Though embraced by extreme alt-righters today, the fascists of WWII Germany generally avoided the term, which was a colloquialism for "dunce" in southern Germany before the war. The word got applied to them when fleeing anti-fascist Germans cleverly abbreviated Nationalsozialist, an already shortened version of the party name. This spread to the countries they migrated to as a general term to encompass Hitler's group (who would've preferred NSDAP). The pejorative colloquialism Nazi was a nickname for Ignatz, a common name much like "John", with a country-bumpkin connotation of stupidity and ignorance. This in turn likely derives from Latin Ignatius, a Biblical name with possible origins in Ancient Greek, or Latin, or something. Honestly, etymologists aren't completely sure. But we are positive about the whole Nazi-insult thing. Believe me.

John Montagu, the Fourth Earl of Sandwich, had a particular affinity for gambling. His addiction was so bad that he refused to get up for meals, ordering his servants to make him his favorite snack, pieces of meat between two slices of bread. Since Montagu was pretty well-known, the sandwich got named after him, and, in an unrelated occurrence, James Cook also named the Sandwich islands in the South Atlantic after Montagu as well. Sandwich was a town in Kent, but before that it was a surname, literally meaning "sand settlement". The first part of the name, sand, comes from Proto-Indo-European bhes (a verb with the definition "to rub"), through Proto-Germanic sandam (also "sand"). The later part of the name, -wich, is pretty common in England, as we can see with place names like Norwich and Greenwich. That's because it meant "settlement". By way of Germanic alterations like wic and wik, it derives from Latin vicus and ultimately traces to Proto-Indo-European weyks, still meaning something like "village".

The word encyclopedia in Latin was spelled encyclopaedia, which was defined as a "general education book", because that's what it was. This is from the Greek phrase enkyklios paideia, which literally meant "circular education" ("circle" kind of meaning a "field of study" here); it was changed to one word by a clerical error. Enkyklos, the "circular" aspect of the term, is from kuklos, "circle", which in turn derives from a Proto-Indo-European root that generally had a kw- sound, like kwel, kwele, or kweklos, and meant "wheel", certainly a type of circle. The en- was just a modifying prefix. Paideia, the latter part of the aforementioned phrase, is the "education" part of it all, from pais, meaning "child", the type of person going through education. Finally, this is from Proto-Indo-European pehw, meaning "smallness". Now, if we harken back to yesterday's post, which explained how wiki actually meant "quick", the website Wikipedia actually means "quick education".

Today, the word wiki is used as a prefix for any site where users collaborate to create content, but as early as 1995 it was an obscure word in Hawaii. This is all because the first person to create a wiki site (the WikiWikiWeb), Ward Cunningham, once visited Hawaii. There, he traveled on the Wiki Wiki Shuttle at Honolulu airport, and learned that wiki wiki actually means "quick" in Hawaiian. This stuck with him years later when he created his site, and now it's stuck with us. So where does wiki wiki come from? The duplication is only there for emphasis; one wiki by itself already means "quick", but it is common in several language families to repeat a word instead of using an adjective like "very". Wiki is likely from a Proto-Polynesian word sounding like witi, but most native terms are poorly researched and it's only speculation from there on.

Cynics might scoff, but cynic used to mean "dog". In Middle English, the word cynic was spelled cynick, cynike, and cynicke, but in Latin it was cynicus (which had a hard initial c, but people messed up the translation), so all those alterations were kind of unnecessary. This comes from Ancient Greek kynikos, which described the Cynics, an actual group of people led by the famed Diogenes. They wore their name with pride, but it was originally an insult, as kynikos literally meant "dog-like", an appellation applied by skeptics of the Cynics who considered them equal to dogs, as many of the sect members lived on the streets and had harsh, aggressive manners, comparable to those of canines. This is from the earlier Ancient Greek word kuon, which just meant "dog", which in turn is reconstructed from the Proto-Indo-European root kwo, also "dog"

Have you ever wondered why the thirteenth element is spelled aluminum in America but aluminium (extra i) England? It's not because Americans modified it to sound less British (as some would be inclined to think); quite the opposite, in fact. Aluminum was coined in 1812 by the British scientist Sir Humphrey Davy. This was readily accepted by the American populace, however British newspaper editors modified it to seem more in line with all the other elements. Ironically, the proper suffix is -en, because that's what it was in alumen, the word that inspired Humphrey's choice. It meant "bitter salt", and was probably extended to the substance name because of the ionic bonds Aluminum creates. Alumen possibly derives from a Proto-Indo-European root sounding like helud and meaning something along the lines of "bitter" as well.

Biblically speaking, a nimrod is a "great hunter". In Genesis 10, he's described as a "mighty hunter before the Lord", and this definition still prevails in some other English-speaking countries. However, in America, a nimrod is an "idiot", a "maladroit". How did this happen? It can all be attributed to Bugs Bunny! In one cartoon, he called Elmer Fudd (the lisping man who's perpetually trying to shoot him) a "nimrod". This was meant ironically at first; Bugs was joking that Fudd was actually a skilled hunter. However, people watching the show in America who weren't well versed in the Bible took it as an obscure insult, and began using it as such. Thus a great shift began; but where does the Biblical word nimrod come from? The truth is that there is no good answers. It has cognates in Aramaic and Arabic, so it's presumably of Proto-Semitic origin, but that's all we can glean.

The word vestigial means a "functionless remnant", and the word vestige means "a remnant" of something rare or extinct, so it's not surprising in the least that the former word derives from the latter. Vestige, which was borrowed into English at the beginning of the seventeenth century from French, traces to the Latin word vestigium, which literally meant "a footprint" but had figurative connotations of a trace left somewhere, which is how we got the word. This does not have a fully understood origin, per se; however, etymologists theorize that it either derives from the Proto-Indo-European root steygh, meaning "to walk", or from PIE wers, which literally meant "drag along the ground" (and would have come through Latin verro, "to sweep"). Ironically, both the words vestige and vestigial have been decreasing dramatically in use since the 1950s, and all we see of them now is a mere vestige.

Most of us who have heard of it only know the bezoar as a tiny antidote stone from Harry Potter. Well, it's an actual thing! An intestinal blockage occurring in the stomachs of goats, and in special cases, humans, a bezoar was believed by alchemists in the Middle Ages to possess curative properties, which is definitely where J.K. Rowling got the idea from. Because of this, it (probably through French) comes from the Arabic word for "antidote", bazahr. This derives from Proto-Indo-European pad-zahr, literally "counter-poison", with pad meaning "against" or "counter" and zahr meaning "poison". The former is from Old Persian pa, which meant "protect" and comes from PIE peh, with the same meaning. The second is from Old Iranian jathra, which meant "to kill" (not that big of a transition), from PIE gwhen, "to strike" or still "kill". So a bezoar means "protecting [from a] kill", and J.K. Rowling knows her Middle Ages superstitions!

In the post about how "pudding" used to mean "sausage", the Latin word botulus was discussed, but it wasn't done enough justice. It comes from Proto-Indo-European gwet, a root which meant "a swelling" and described how sausages tend to bulge, but that's not the fun part. You may have noticed that the word sounds like botulism, a condition with swelling in it (thus the connection) and often leading to paralysis. Botulism is caused by the botulinum toxin, also named because of the swelling it causes. However, in 1987, two scientists accidentally discovered that the botulinum toxin softens your face and diminishes wrinkles. When the rights to this were bought by Allergan, they cleverly combined the words botulinum and toxin to make botox, a staple of the cosmetics industry. So, something we inject in ourselves is actually something that is poisonous, and that which is poisonous is actually just a hot dog. Bon Appétit!

|

AUTHORHello! I'm Adam Aleksic. I have a linguistics degree from Harvard University, where I co-founded the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society and wrote my thesis on Serbo-Croatian language policy. In addition to etymology, I also really enjoy traveling, trivia, philosophy, board games, conlanging, and art history.

Archives

December 2023

TAGS |