|

According to both Google Trends and my observations of the world, the word emoticon has been decreasing in usage of late, in favor of emoji. Both describe a small digital picture often used on the Internet, and both sound similar, but the roots are different, etymologically speaking. Additionally, a schism in definition caused "emoticon" to mainly mean characters created out of text, and "emoji" to be ready-made images. Emoticon, which was coined by 1994, is a portmanteau of the words emotion and icon, which is pretty self-explanatory. Emoji is much cleverer. Shigetaka Kurita, the man who invented the modern pictorial variation, named them that as a sort of play on words: it sounded like both emoticon and kanji, a Japanese system of writing, but actually combined the words e, meaning "picture", and moji, meaning "character". Best pun since Shakespeare, in my opinion. E is very simple and therefore has a very simple etymology. It probably comes from a Chinese word meaning "drawing" and sounding like huay, which always sounded like that and meant that. Moji, meanwhile, is thought to be from Middle Chinese midzi, meaning "writing-character", also without much change before that. So an emoji carries the hidden meaning of "drawing-writing-character"!

0 Comments

Somebody suggested to me today that the word shampoo means "fake excrement". Sham poo. Well, that was definitely wrong. When the word shampoo was first brought to England in the 1760s by merchants who picked it up from Hindi champo, it meant "massage". This, however, was a special type of Hindu massage where they would slather your body in foam first, and gradually the "foam" meaning emerged to prevail, mainly due to Victorian hesitation about embracing those seemingly promiscuous massages. Anyway, champo comes from capo, which meant "to press"- an obvious connection, because you need to press on the back in a massage. This has unconfirmed and hypothesized origins, but the main theory is that it comes from the old Sanskrit term capayati, which meant something like "knead". If this is correct, this would further derive from the Old Indo-Aryan root canp, with about the same definition.

Both the xebec and the sambuk are relatively similar types of ships, and both have weird names that are relatively similar in construction. Sadly, they aren't confirmed to be related in origin. The xebec, the main focus of today, is a small and speedy kind of boat used to navigate the Mediterranean in the olden days. It is evident from a glance that this word is foreign, and anything foreign involved with Mediterranean trade must have come from the Arabs. This glance proved to be accurate, because, through French chebec and Italian sciabecco, and under Spanish influence, xebec comes from Arabic shabbak, with the meaning "small warship", only a slight deviation from today. This is from the Proto-Semitic root s-b-k, which meant something like "net", because wood had to be intertwined like a net to make the ships. Meanwhile, sambuk came from Middle Persian and most of the etymology is obscure to us. Note the letters s, b, and k, and the unconfirmed origin. Perhaps there's the slightest chance...

Catsup is just another way of writing ketchup (to make it sound more Anglo-American), which was originally spelled catchup. The origin for this is not known for sure, but there are several interesting theories. We know it was borrowed in 1690 from trade routes, and there is a Malay word, kichap, to describe a very similar condiment, but even that is likely borrowed from sea trade as well. There are cognates all around the South China Sea, indicating that the word might derive from that region. There's the Indonesian word ket-jap, meaning "soy sauce", there's the Malay word kicap, with the same meaning, and there's the Min Nan dialect of Chinese word koechiap, meaning "fish brine". The predominant theory is that all others derive from this latter one; if so, you can also see the evolution of the liquid from sour to sweet and tangy, and from fishy to tomatoey. I thought that was cool.

The word gypped comes from gypsy, but gypsum does not. Gypsy, considered a slur by the Roma people, has an origin that reflects the uneducated bias against them. In Middle English, it had alterations ranging from gipsy to gypcyan to gipcyan. All of this derives from the Old French word gyptien, which was a shortening of egyptien, meaning "Egyptian". This is a misnomer; people incorrectly believed that the often-darker-skinned traveling groups came from Egypt. The clipping process of losing the e is quite common in English, and there are many similar examples. Egyptien derives from the Latin aegyptius, from the Greek aiguptios, which, unsurprisingly, is likely Egyptian in origin. It is believed that the word traces to hwt ka pth, a phrase meaning "the temple of Ptah's soul", but that's unconfirmed. If so, the roots are clearly Semitic and come from another unintelligible spelling, for sure.

Turns out that the word Tory used to be an insult. Now interchangeable with the word conservative in England, the original Tories were highwaymen! The word was attested in its current form in 1566 to describe a gang of Irish bandits, and meant "outlaw". In the mid-1600s, it was used to describe displaced Irish farmers who often turned to crime, and, in the late 1600s, it became a vulgar term to describe supporters of (Catholic) King James II. This is when Tory became a badge of pride, as some of the aforementioned supporters took on the designation and it came to mean someone on the side of the monarchy in general. It's easy to see how this evolved into the name of a political party. Now, to go backwards in time! Since all this came from Ireland, it's not surprising that Tory is an Irish word. The "outlaw" meaning comes from toruighe, or "plunderer", which, through a connection of searching for money, comes from toirighim, "to pursue". This derives from the Old Irish word toir, meaning "pursuit", and, through a mess in Proto-Celtic, probably goes back to a Proto-Indo-European word for "run".

Yesterday we examined how polecat really means "chicken cat"; today, let's look at the word polemarch and why it's completely different. It would appear that two words, pole and march, are combined (in this military title). While there is a portmanteau, it is a bit odder than expected: polemarch turns out to combine the Ancient Greek words polemos, meaning "war", and arkhos, meaning "leader" (so the portmanteau is of polem and arch). Polemos is of unknown, Pre-Greek origin, but arkhos is reasonably well documented. It is from the verb arkhein, meaning "to be the first", and that in turn is from Proto-Indo-European hergh, meaning "begin". You can see here how the definition shifted from "start" to "lead", and in all honesty, that's not that surprising. So, there you have it: polemarch means "beginning war".

A fun fact on polecats: they only exist in Europe, so whatever you thought were polecats in America are actually either ferrets or skunks. Additionally, it's related more closely to the dog than the cat, so there are two misleading animals in its name. Yes, two. The word polecat is a portmanteau of two Middle French words: pole, meaning "chicken", and cat, meaning "cat". It was so named because it looked like a cat and liked to eat hens. Anyway, pole, which is related to the modern-day French word for "chicken", poulet, comes from the Old French word poule, which in turn derives from the Latin word pullus, meaning "young animal" but especially referring to birds. This ultimately originates from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) reconstruction pau, meaning "little". Onto cat; it would not surprise anyone that it has the same root as English cat. Indeed, both words can be traced to Latin cattus, by one way or another. This is a curious word with an origin likely not grounded in the Indo-European languages, but that's all we know. So, the doglike polecat actually has a name meaning "chicken cat", or "little cat", depending on how far back you go. But, whether "chicken" or "little", the cat always remained.

Though the community had one of the greatest cultural impacts on America, Harlem has a dirty etymology. When New York was founded in 1624, it was called New Amsterdam, after the capital of the Netherlands, and was under Dutch rule. Similarly, when Harlem was created in 1658, they called it New Harlem after a city in the Netherlands named Haarlem (the New was subsequently dropped in a shortening). That Haarlem is currently a suburb of Amsterdam with a decent-sized population of 160,000, but where did it get its name from? Dutch, obviously: the first part, haar, meant "height", and the second part, lem, meant "silt", referring to it being on a high bank of a local river. For some reason, I couldn't find origins beyond that, but this is no doubt Proto-Germanic, and, by extension, Proto-Indo-European. It's pretty weird thinking of a hidden Dutch presence under a black cultural center, isn't it?

In the later days of World War II, when Japan knew they were going to lose but tried to drag on the war to discourage America, they began sending planes to fly into other ships. This suicide was also considered an honorable death by many Japanese. Of course, they needed a patriotic, inspiring name for that act. So they used kamikaze, which previously was the term for the storms which destroyed Mongol fleets as they tried and failed to invade Japan. The idea was that these pilots were each an individual storm, used to prevent a foreign power from conquering the land of the rising sun. Anyway, kamikaze is a portmanteau of two other words, kami, meaning "godly", and kaze, meaning "wind", again showing the serendipitous yet divine intervention the Japanese believed made them superior to invading barbarians. Kami comes from kamu, meaning "god", and has cognates in Ainu kamuy and Korean kom, so is likely from Proto-Japonic or some other such localized language family. I can't find any sources for kaze (Asian words are a nightmare to etymologize, since the characters and meanings have separate origins, and they're poorly researched), but it likely follows a similar path.

As words commonly did in the decentralized and unstandardized language of Middle English, garlic had a lot of variations in the olden days. It took forms including garlic, garlick, garleek, garlicke, garlek, and garlec, all of which derived from the Old English word garlic, which literally meant "spear-leek", comprising the terms gar ("spear") and lead ("leak") and supposedly earning that name because of the shapes of the individual cloves. Gar is from the Proto-Germanic word gaizaz, still meaning "spear" but with side definitions of "pike" or "javelin", and is ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European root gey, meaning "to throw", since you throw those things. Meanwhile, leac came to us through the Proto-Germanic word laukaz, still with the same meaning. Officially, the origin past here is unknown due to a lack of non-Germanic cognates, but some etymologists theorize that it could be related to the Proto-Indo-European root lewg, meaning "to bend". That's just guesswork, however. Oh, and the adjective form of garlic, garlicky, includes the k to preserve the hard c sound.

Fun fact: urination isn't even the proper scientific/formal term for peeing; it's micturate. That being established, urination is clearly the act of producing urine, a word that was borrowed into Middle English from the Old French word urine, alternatively orine. This in turn derives from the Latin term urina, which still had the same meaning, which is reconstructed as deriving from the Proto-Indo-European zero-grade uhr, meaning "liquid" but mainly carrying connotations of water or milk. That same root, uhr, later became the Latin word umere, an infinitive meaning "to be moist", but, like humble pie, a phrase we've already examined, it added an h because of shifting pronunciational giving us the verb humere, which could be conjugated to yield humidus. From the modern-day similarities and the title of this post, you can probably guess what's coming next: (through French humid) this gave us our word humid, still meaning "moist" and now proven to share a root with the word urine through a hypothetical ancient root meaning "milk". Etymology is amazing!

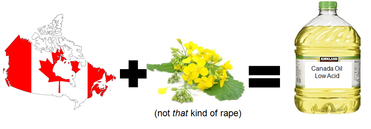

The term canola oil is an etymological outlier in so many senses: it is an acronym, it is a euphemism, it is redundant, and we got the word because of rape. This might confuse you, and rightly so, but here I discuss rape the plant, a mustard which yields rapeseeds. These rapeseeds were popular for use in creation of cooking oils- cooking oils with dangerous high-acid health effects that were eventually banned by the CDC. Then, in the 1970s, two researchers at the University of Manitoba created a safer version and decided to market it. However, there was so much negative stigma around rapeseed oil because of the past hazards and the fact that the word rape was in there that they decided to call it canola oil, the first element combining the words Canada Oil, Low Acid. This, of course, repeats the word oil twice when you say canola oil, making it all the more interesting. To this day, Canada is the world's largest rapeseed producer, but it's all hidden under the pleasantly Italian-sounding guise of canola. Help expose the conspiracy!

Thanks to Thomas Ottaway for the inspiration to write this particularly interesting blog post. The current meaning of thesaurus was first attested in 1852 in Peter Roget's Thesaurus. He borrowed an existing word meaning something more like "encyclopedia" for that book title, which was borrowed in the 1500s from Latin thesaurus, which actually had a definition more like "treasure" but had a figurative meaning of "repository" through a shared meaning of "treasury". This comes from Ancient Greek thesauros, which could have been defined as "vault", "chest", "treasure", or anything along those lines. Prior to that, we can trace the word as from Ancient Greek tithemai, meaning "to place", from the Proto-Indo-European dhe, "to set". Right around the '60s, thesaurus rapidly began to increase in usage, which is correlated with increased purchases of thesauruses (a plural which is more correct than thesauri, but both variations are allowed). Well, that's that. Treasure your words.

In 1882, P.T. Barnum purchased what was allegedly the world's largest elephant for his traveling circus show from the London Zoo. This elephant was named Jumbo, as many elephants today are called as well. However, this jumbo is set apart because it was the first to hold that name. It was not named after a word for "big"; a word for "big" was named after it. That's all really cool, but where does the original name come from? Most definitely an African language, but which one, and what did it mean before? There are several theories proffered in response to this query. Some etymologists think that it was the word for "elephant", which would make sense; in the Kongo language, "elephant" is nzamba. Then again, it could be from Swahili jambo, meaning "thing", or Swahili jumbe, meaning "chief", or it could generally mean "clumsy person". And as for the phrase mumbo-jumbo, it seems to have come earlier, being first attested in 1738. It seems that the original mumbo-jumbo was a shaman chant, which got extended to "meaningless babble". However, since that too is most likely African in origin, it cannot be discounted from relation to jumbo. Philologizing non-Indo-European languages, especially ones without writing systems, is exceptionally difficult, so we really can't go much further than that.

The word yodel comes from the German word for the action, jodeln, which comes from yo, an onomatopoeic expression of "joy", or a word literally meaning "joy". But even though it's a word that sounds like "joy" with the same meaning, we can't trace it to the origins of "joy". It's definitely a possibility that it may have been influenced by the latter, but yodel honestly seems like it's imitative in origin. Weird. Anyway, the word joy comes to us from Old French joie, from Latin gaudia. While both meanings could be interpreted to be the same as today, both definitely also had sexual connotations as well. Looking at the infinitive gaudere, this ultimately this is from a Proto-Indo-European root sounding like gahu or gau, which had a definition more along the lines of "rejoice". Now, this is beyond the book, but I would not be surprised in the least if yodel also traced to that. The given etymologies we take for granted are always incomplete and sometimes inaccurate, so who knows?

Stephan Ladislaus Endlicher was a bit of a polyglot: an Austrian native, he developed great interests in the studies of everything from coins to linguistics to China to plants. However, it's his curiosity for botany that mattered most, as he decided to categorize a newly discovered tree species as a genus, contrary to the simple species its discoverer (an English botanist) had identified. Endlicher called this a sequoia, and the word has stuck in English to today. However, Endlicher did not leave any reasoning behind the name origin, which is problematic. Perhaps he just wanted to mess with future etymologists. The predominant theory is that he named it after Sequoya, an Amerindian who created a writing system for the Cherokees, which would make sense, taking into account his interests in language. Well, that's literally all we know.

To be savvy is to be wise or intelligent, but that's such a strange and non-Germanic word. Where does it come from? The origin is surprisingly interesting: it is most likely from the French question savez-vous?, which literally means "do you know?". Alternately, it could be from Spanish sabe?, with the same translation. Somebody savvy would be somebody who knows- therefore the word. Either way, this goes back to the Latin root sapere, "to be wise". In Proto-Italic, wisdom had a lot to do with discerning, so as sapio, it meant "discern", however you discern tastes, so before that it meant "taste". This is why, as the Proto-Indo-European root sep, the word also meant "taste". Usage of the word savvy has been exponentially increasing since 1980, and, with that, I can conclude that we now know the way.

The word disaster has such a "star-crossed" etymology. Well, that's literally what it meant as Italian disastro, from whence it came (through Middle French desastre). Here we can separate it into two parts: dis-, the prefix we use for negating words, and astro, which meant "star". Hopefully, now you can see that a disaster only occurs because of negative stars- or so the Italians would have us believe. Astro continues its backward journey as we reach the Ancient Greek word astron, also meaning "star". Through a Proto-Hellenic root probably sounding like aster, this is reconstructed as deriving from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root hehs, meaning "to burn". Yes, this is the same etymology as for the prefix of the word astronaut, which literally means "star sailor" itself.

Somebody from Arizona is an Arizonan, somebody from Montana is called a Montanan, and somebody from Indiana is called a... Hoosier? I mean, Indianan is a word, but perhaps it's not as popular because it sounds redundant, and the word Indian was already taken of course. Reflecting on this, it seems inevitable that a new demonym had to be created, but what does Hoosier even mean? Well, no one seems sure, so let’s delve into a realm of guesswork. We know that it became popular by the 1830s, but before that, it could have been everything from a combination of who’s there? to an Indian word for “corn”. The most possible explanation, however, is that it was a dialectal term for “redneck” or “hillbilly”. This could have been from an earlier word spelled like hoozer and probably pronounced differently, with Anglo-Saxon origins. Nothing is for sure, though, as with all etymologies.

In the Middle Ages, lots of people lived in wooden houses. Quite understandably, they were very concerned about fires breaking out. Thus, at a specified time every night, a bell would be rung in those medieval villages, as a call that it was time to put out the fires and go to sleep. These were known as curfews. The word is a shortening of the Old French word cuevrefeu, which meant "cover-fire", something you would do to put it out (and no, not to support your military unit). In imperative form, this is literally a portmanteau of "cover" (covrir) and "fire" (feu). Covrir is from Latin cooperere, with the same meaning. Then we eliminate the prefix con- to get operere, which still meant the action of covering something (which made the con- sort of redundant, to be honest). This is from Proto-Indo-European hepi, meaning "near", because PIE is weird. Going back to feu, "fire", is a much shorter journey to us, being a shortening of the Latin word focus, meaning "fireplace", for which we have no etymology. It could be everything from Greek to Armenian to PIE again, so here we give up and accept that the real reason firefighters exist is to impose curfews.

In 1759, a French Treasury Chief named Étienne de Silhouette was forced to pass unpopular taxes on basically all classes, so as to help pay for the extremely costly Seven Years' War, which debatably was the first truly global conflict. Naturally, the public was very angry, and expressed it by calling all cheap or miserly things à la Silhouette. This surprisingly stuck long after his death in 1767, all the way to 1798, when darkened profiles of people emerged as the cheapest way to make portraits (this only became popular in the nineteenth century). Thus, since they were inexpensive, the portraits became known as silhouettes, a word that still exists today, obviously. Curiously, Silouette's name was likely Basque in origin, coming from a term sounding like zilhoeta or zilhoeta, with roots in the word zulo, meaning "hole". Today, usage of the word silhouette is most common in the United States and has been steady since about 1930, before when it was steadily increasing (although modern search frequency has been on the rise). So, in summary, there you have it: during the French revolution, a word once meaning "hole" became a new word for a type of painting! Etymology is amazing.

The word muscle came to us in the late fourteenth century from the Middle French word muscle, with basically the same meaning (there were some weird alterations along the way, like muskylle and muscule, but history has canceled those out). This too was borrowed in the fourteenth century, albeit from Latin. In this case, the word in question was musculus, which too meant muscle... figuratively. It carried quite a different literal meaning, that of "little mouse"! The connection occurred because muscles really do sort of look like tiny murine lumps under your skin. Musculus is a diminutive of mus, the normal word for mouse. Through Proto-Italic mus, this is reconstructed as having derived from the Proto-Indo-European word muhs, still meaning "mouse". Curiously, correlations between mice and muscles can also be found in languages from Arabic to Greek to German, as well.

Ambulances as motor vehicles have been around since 1909, but the history of the word ambulance is much older. The word entered English in 1798, with the meaning "mobile hospital", describing entire camps that would move with armies. It's easy to see how the definition was extended, and the connections continue as we go back. In the original French, ambulance was actually hopital ambulant, which meant "walking hospital" (over time the hopital was clipped out). The ambulant part goes back to the Latin word ambulare, which "to walk"- not a large stretch from a camp but a huge one from speeding, screaming automobiles! Through French, this is also the source of our words ambulate and amble, both meaning "to walk" or even "stroll". It is theorized that ambulare derives from the Proto-Indo-European root ambhi, meaning "around", as in "stroll around". Gee, it's a good thing ambulances have sped up...

Lemurs! The innocuous, even playful ring-tailed animals us kids know from the movie Madagascar. Their name was given to them by none other than Carolus Linnaeus in the late eighteenth century, who, in a stroke of whimsy, named them lemures, which literally means "spirits of the dead" in Latin. The name was applied because of their slow gait, nocturnal habits, and generally sketchy looks. Anyway, the etymology of lemures is surprisingly obscure. Philologists can connect it to the Greek word lamia, meaning "monster", but since no other relatives exist, some hypothesize that the lemur actually has its origins in a non-Indo-European language such as Proto-Etruscan or Proto-Anatolian. Both of those are poorly researched, so there's little chance we'll find out soon. At least now you know to keep an eye out for dead spirits next time you visit a zoo.

|

AUTHORHello! I'm Adam Aleksic. I have a linguistics degree from Harvard University, where I co-founded the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society and wrote my thesis on Serbo-Croatian language policy. In addition to etymology, I also really enjoy traveling, trivia, philosophy, board games, conlanging, and art history.

Archives

December 2023

TAGS |