|

Sorry, biologists, a population is supposed to be composed of only humans. Sorry, cool kids, being popular is actually being like all other humans. Population is from the Latin nominative populatio, "a people", from populus "people". Popular (of which pop, "cool", is an abbreviation) originally meant "public" in Middle French as populier. This is a borrowing from Latin popularis, or "belonging to the people", which stems from populus. Likewise, the word people comes through French as peupel to go back to populus. Clearly a very popular word, populus is also the direct etymon of the now-ubiquitous term populist, which means "of the people", the Spanish word pueblo "town", and the Italian word popolo, or "people". However, for all that linguistic significancy, we don't know what comes next. The main theory traces it to Etruscan (which would go further back to Proto-Tyrsenian), but we have no clue about that. The word poplar, as in the tree type, also goes back to a Latin word populus, but it was a homonym with no semantic connection (the word went on to develop from Old French poplier and Anglo-French popler, and is supposedly from Proto-Italic poplo, "army", and also probably Etruscan. BUT IT HAS A TOTALLY DIFFERENT HISTORY).

1 Comment

The word chronic and the word chronicle haven't shared the same root since before the time of Christ. Chronic ("over a long period of time") traces to the Middle French word chronique, from the Latin word chronicus. This in turn is from the Greek word khronikos, which meant "of or pertaining to time". On the other hand, chronicle ("a written account") is from Anglo-French cronicle, from the Old French word chronique. This latter word differs from the one in the history of chronic semantically; it was a homonym and nothing more. Going farther back, the h was reinserted during Latin chronica, which was a modification of Greek ta khronika, or literally "time book". Here it meets chronic finally under khronikos, which is from the word khronos, which incidentally was the name of the Ancient Greek god of time. After that it's uncertain. It is likewise uncertain that a God created language, but now we know that one of them created at least two words!

This was a requested word. The word toilet actually has really unexpected origins. I'll start from the back: in Proto-Indo-European, there was the word teks, which meant "cloth". This eventually became the Latin word texo, which was affixed to the suffix -ela (which forms abstract nouns) to make tela. This hung around the Italic and later Romance languages until it was altered in Old French to the form teile, which was altered into toile. It still meant "cloth" at the time. As this became toilette in Middle French, the word took on the meaning of "clothes", not much of a semantic shift at all, even as it finally became toilet in English. But as the word developed in English, it took on more of a "putting on clothes" meaning, then a "dressing room" meaning, since you put on clothes in a dressing room. Many aristocratic dressing rooms had early plumbing fixtures, and thus the word became applied to those plumbing fixtures; the earlier uses were altogether dropped.

The word planet reflects old scientific theories surprisingly well. It first appeared in Old English as planete, and this was a loanword from the Old French term planete, ultimately from the Late Latin word planeta, mostly used to discuss any celestial body with a path of its own. The word shifts back to planete as we travel back to Greek, and here it gets interesting. Planete was actually the shortening of a phrase, asterea planetai, which literally meant "wandering stars" (since that's how the Greeks differentiated planets: by movement). We've already discovered where aster came from, in the post about "astronaut", bit planetai was the part meaning "wandering", and originally came from the word planesthai, also "wandering". There ate two main theories as to what happens when we move further back: planesthai may have originated from the Proto-Indo-European term pel, meaning "to roam", or, more whimsically, from the Proto-Indo-European term pele, which meant "flat" and would have figuratively meant "to spread around". If the latter is true, then we can truly say our planet is "flat"!

It might be a little stereotypical, bagels are definitely Jewish, at least by origin. The word entered English in 1919 as Germans entered America: it was originally the Yiddish word beygl, with the current definition. This is from Middle High German, the forefather of both Yiddish and German, and where the word was boug, which meant "ring" or "bracelet"; the correlation is clear. Boug is from the Old German cognate boug, which derived from Proto-Germanic baugaz, specifically meaning a "ring", which is reconstructed as being from the Proto-Indo-European root bheug, or "to bend", since a circular "ring" had to be "bent" into shape. Fun fact: an alternative British English spelling of bagel is beigel, though usage is decreasing. This happened naturally as separate cultures developed and is not intentionally modified. However, this spelling is unique to Great Britain and remains nine hundred times less prevalent than what we know as bagel. There are approximately 150 people with the last name "bagel" in the United States.

In recognition of World Malaria Day, I recognize malaria as having come from the Italian term mala aira, which literally meant "bad air". A word present everywhere from Irish to Spanish, mala ("bad"), is from Latin (in this case from malus, also "bad"), as most Italian words are. This is likely from Proto-Italic malo, from Proto-Indo-European mol, which generally encompassed nasty words like "evil", "treachery", and "destruction"; some people, however, claim it has Greek origins. Aria is, unsurprisingly, derived from Latin aer, which is also the etymon of the English word air (through its French cognate). This is from the earlier, heavily accented Greek word aer, which is from Proto-Hellenic auher, or "morning mist". This very likely has a connection with the Proto-Indo-European reconstruction hews, which meant "dawn" and, ipso facto, has a clear connection with both "mornings" and "air".

A long time ago, the Akkadians associated the phoneme karsu with the morpheme concerning trees bearing tiny fruits. The rest is history, as the word passed into Anatolian and then Greek (following geographical lines, I might add), as kerasos and specifically applying to the bird cherry tree. This logically created another noun, that of kerasion, or "cherry", as an -ion suffix was affixed. As many Greek words did, this passed into Latin, and as all Greek words with a k that pass in to Latin change into a word with a c, as did did kerasion, which became the word cerasium, later ceresium. In Vulgar Latin, this became ceresia, and in Old Northern French it became cherise (nothing to do with mon cheri). This then became a loanword as it crossed the English channel to become cherise, and here people began to use it daily until someone along the line "realized" that this was a plural, and that was incorrect, so that person decided to abridge it to something like cherri, which became cherry in due course. Folk etymology fools us again! A thousand curses. The slang for cherry meaning "a woman's virginity" is a vulgar term from the nineteenth century, and still much less in usage than the meaning of "type of fruit", thankfully.

Sarcasm fascinates me so much, I just had to write this. The word came from Late Latin sarcasmus, which in turn derived from the Greek term sarkasmos, which meant "a sneer or taunt". Pretty standard so far, but here it gets interesting. Sarkasmos derives from the earlier word sarkazo, which had varying degree of literalness as it changed over time: going backward, it meant something like "an angry sneer", from "gnashing teeth in anger", ultimately from "I strip off the flesh". This last definition is the closest to the root of the word, and developed to what it is today through becoming increasingly figurative (there wasn't much application for the word in its first form, of course). Sarkazo is a combination of the root sarx, meaning "meat", and the suffix -azo. Sarx derives from the Proto-Indo-European word for "cut" (an instance of anthimeria, it became so since you "cut" "meat" when eating), twerk. No, not that twerk: this is an archaic root. Fun fact: usage of the word sarcasm has decreased from the nineteenth century.

The word milord brings to mind someone like Grima Wormtongue from Lord of the Rings, an oily, subservient creature bowing so low to some noble that his greasy nose scrapes the ground. Imagery aside, the word has a fascinating history. Contrary to popular belief, it is not a contraction of my lord. Rather, milord is borrowed from the French word milord, which in turn is an alteration of English my lord. That's right: milord was borrowed from a foreign word which was borrowed from a domestic word, an unusual exchange in linguistics and a textbook example of a semantic loan. Apparently the re-borrowing was meant to be ironic at first, but was soon lost in translation. My is a reduced form of mine, which is from Proto-Germanic minaz ("mine"), itself from Proto-Indo-European meynos ("mine"). Lord has a much more interesting origin: it used to be, in Old English, the term hlaford, which was a portmanteau of the words hlaf, meaning "bread", and weard, meaning "guardian". Thus a lord was a "bread-guardian". Hlaf is from Proto-Germanic khlaibuz, and weard is from Proto-Indo-European wer ("to watch out for, through Proto-Germanic wardon, or"to guard"). The term hlaford itself was designed to imitate the Latin word dominus, referring to a more powerful individual. There were also Greek and Hebrew influences in its construction; the fact of the matter was that aristocratic English people needed a good term to distinguish themselves from the plebeians.

Spinach is quite the well-traveled word. The earliest it can be traced to is the Anglo-Norman word spinache, which in turn comes from the Old French term espinache. At this point we get involved in the history of the word itself: since spinach was first introduced in the Provence region of France, the word can be traced through the local language of Provencal French, where it took the form of espinarc. Since the vegetable was introduced to Europe by the Arabs, the etymology next goes back to Arabic, as isbanakh. Finally, since Spinach is suspected (by horticulturists) to have originated in that area treading the line between the Middle East and Central Asia, we can trace the word further eastward. The word didn't change much as it went back to Persian ispanakh, from Proto-Iranian spai. You might be noticing a lack of semantic change here; the morpheme was just associated with spinach for a very long time. That changes with the Proto-Indo-European term spei, meaning "thorn-like", and we can go no further.

The word marijuana has quite the muddled backstory, and was omnipresent throughout Latino linguistic culture. The word was first attested in its current usage under the form mariguan, in an 1894 edition of Scribner's Magazine. This seems to be where most other forms of the word stem from, mostly switching the centric g with an h: variations such as marihuma, mariahuana, mariahuano, marihuano, and marihuana could be seen to crop up in the next twenty years. In the late 1910s, several newspaper articles and bits of gossip unfairly attributed the drug only to Mexicans, and so people began to folk etymologize the word. Since weed was thought of as Latino primarily, people began to alter the word to marijuana from the most-common marihuana simply because the new form sounded more like a common Hispanic name, Maria Juana. Indeed, some people persist to today in calling it Mary Jane, another derivative of this false and somewhat bigotedly folk etymology. But where did mariguan come from? Etymologists theorize that it is of Native American origin (like the cultivation of the plant), and it may stem from the Nahuatl word for "prisoner", presumably because one under the influence of Mary Jane was a "prisoner" to the effects of the depressant. If this is true, marijuana is ultimately of Uto-Aztecan descent.

An excellent, contributing research article about this may be found here: www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp153_marijuana.pdf The titular slang for Chicago is infinitely more whimsical than it lets on. The word Chicago is from the Native American language Potawatomi, where the phrase shikaakwa, or "place of the smelly onion", became eponymous with the place that is now the third-largest American city. This is not uncommon; Native Americans often attributed food names to locations. It is also not uncommon for foodstuffs to have been named after animals, so it is unsurprising that shikaakwa comes from the Proto-Algonquin word sekakwa, which meant "skunk". The "smelly" semantic connection is evident. This is reconstructed as coming from the earlier Proto-Algonquin root sek, which meant "to urinate" and further displays the continued prevalence of smell in the definitions (additionally, it may have combined that with the word for "fox", but this is on shaky ground). From that very same prior word (sekakwa) we get our current word for skunk; it passed through the Abenaki language as segonku and was colloquially known as squunk in the area until the current spelling was coined in the mid-seventeenth century. A brief point of interest: a Chicago study by Nina Fascione, et al., found that there were over 4000 skunks "handled by wildlife control operators in the Chicago metropolitan area". Oh, the irony!

There are several types of cardinals, and all of them have the same origin. The sense of cardinal as a type of bird originated in the 1600s when they were discovered, and was named so because the birds' plumages resembled the robes of a religious cardinal. The word cardinal as pertaining to the ecclesiastical rank derives from the Latin word cardinalis, meaning "principal and essential". It is obvious why this would come to be; religion and religious authorities were paramount at the time. Coincidentally, it is from this same word (cardinalis) that the word cardinal pertaining to direction originated from (think cardinal points on a compass rose), since those directions were about equally significant to daily life at the time. Now, since cardinalis had a meaning of "pivotal", this next change kind of makes half-sense: the term is a portmanteau of the Latin word for "hinge" (cardo, since a hinge is pivotal too) and the irrelevant suffix -alis. This is interesting as it is, but countless possibilities open up with the fact that where cardo comes from is unknown. One interesting theory would make cardo a cognate with the English word hinge: it is possibly from the Proto-Indo-European word nerd ("swing"). Other conjectures follow this to Greek, but we'll never know for sure by which way fate swung cardinal our way.

The word flatulence didn't always carry such a noxious connotation. It was coined in 1711, but not really, since it's a direct loanword from French flatulence. This is from the Middle French word flatulent (from which we got ours; it's much older than the former), which meant (as today) "affected with gas". This is from the modern Latin word flatulentus, a variation of flatus, a jack-of-all-trades word dealing with air, including definitions such as "blow", "breathe", and "snort". Not necessarily smelly, I might emphasize. One theory traces this to an earlier word, flo, meaning "to breathe or blow". This would be (through Proto-Italic flao) from the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European root bleh, or "to blow". This possibly has connections to another Proto-Indo-European word, bhel, which meant "to swell" and connected to all this since you swell up before blowing out air. What we can see here on a grander picture is that one type of air release became another over time. Fun fact: the word flatulence had a 300% higher usage during 1867 than it does today; it's losing popularity both to euphemisms like passing gas and cruder words like fart, both of which have increased in usage since then.

The word soccer was actually invented in Great Britain, and how it came to be is shocking indeed. Back in the late nineteenth century, when universities and organizations began playing the game seriously, they called it association football. This is self-explanatory; the word football already existed (with a transparent origin), and the preceding term association denoted that they played in official federations. However, among college players, a colloquial version of the word appeared: socca, which was an abbreviated version of as-socia-ted. This became rather popular to say and was soon picked up by Americans playing the game. Because of their linguistic patterns of adding jocular formations, especially around New England, where it was most popular, the word took on an -er ending and thus became soccer. This grew in usage until every American was saying it, while the Brits were still split fifty-fifty between socca and football by itself. By the 1980s, the newly headstrong and Thatcherized English wanted to distinguish themselves from those vulgar Americans, and stopped saying socca altogether. Now everyone thinks we wanted to change from them! Speaking of fake etymologies, at one point the term socker was also attested, which would have caused a bunch of amateur origin-guessing if it had survived the natural selection process. Luckily soccer's spelling was becoming much more standardized, and this didn't occur.

Most other basic nouns are Germanic in English, but you can just tell off of the ou- that this is French. Indeed, it derives from the word cosin, entering our language around when the Normans invaded. This is from the Latin word consobrinus, which also meant "cousin". However, as we move backward in time, an older form of the word is revealed: consobrinus once had a much more specific definition, that of "the son of your mother's sister". Yes, cousin was once exclusive to the mother's side of the family. Consobrinus is a portmanteau of the prefix con-, "with", and the root sobrinus (the etymon of Spanish sobrina, "niece"), still with the same definition. This is from the even earlier root soror, meaning "sister", which allegedly stems from the Proto-Italic word swezrinos, "of the sister", from Proto-Indo-European swesor, also "sister". Here it gets even more interesting: the PIE word may be a compound of swe, "self", and hesh, "blood", since a sister has the "blood" of your "self". Interesting...

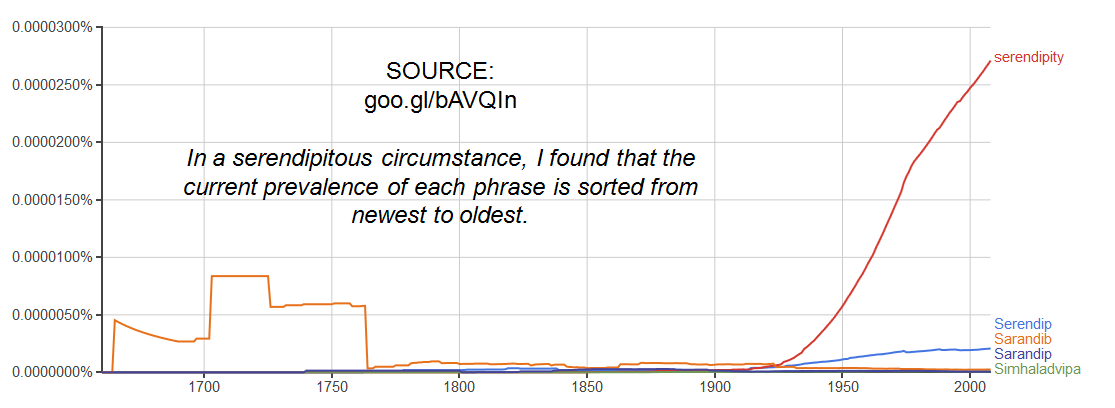

Serendipity, a surprisingly complex English word describing a happy coincidence, has often been polled to be people's favorite word in English. It was coined in 1754 by Horace Walpole, the 4th Earl of Orford and Whig politician, as a reference to the island of Sri Lanka. This is not surprising because at the time, Serendip was another name for Ceylon, which is another name for Sri Lanka. The Earl coined this in the fashion of a fairy tale where three royals from Serendip make several accidental discoveries; thus the word occurred. Anyway, the proper noun Serendip is from Arabic sarandib, from Persian sarandip, which in turn is from Pali sihaldipa. We're getting pretty far back now, but it goes even further to Sanskrit Simhaladvipa, or "lion's dwelling island" , a portmanteau of simha, "lion" (note the connection to Swahili simba, "lion" and the Telugu word simhamu, "lion"; this is from the earlier word simh, or "to mount". Connections to Telugu are proven but connections to Swahili seem unlikely) and dvipa, "island". We can go no further here, but it's whimsical enough as it is!

Money can buy happiness, at least etymologically speaking. The word jewel (through Anglo-Norman juel) derives from the Old French word jouel, or "ornament". There is some debate on where this word comes from, but both theories lead to Latin. The more widely accepted school of thought is that jouel ultimately is from the titular Latin word jocale, meaning "that which causes joy". Since both games and jokes cause laughter, which is associated with joy, it then makes sense that the next step back takes us to the other Latin term iocus, "joke or game". This, through Proto-Italic joko, would ultimately stem from the Proto-Indo-European word for "word", ioko. The other main theory is semantically similar: it suggests that jouel comes from another Latin word for "joy", gaudium. Phonemically, this is kind of a stretch, but if correct, this would take us back to the Proto-Indo-European word gehu, or "to rejoice". Maybe diamonds really are a girl's best friend...

The word magenta has surprisingly militaristic origins. In 1859, the Second French Empire (under Louis Napoleon) crushed the Austrian empire in the Battle of Magenta (in Lombardy). At the time, the victory was monumental, and when British dye chemist Edward Chambers Nicholson had the chance to name the color that same year, he did it after the battle. The color was associated because of the hue of the French soldiers' uniforms, and soon became ubiquitously known as it is. But where did the name Magenta come from? It had been around for ages, and before the battle no one bothered to etymologize it, so our knowledge is vague. It seems to be a remnant of Roman times; supposedly Magenta was named after the emperor Marcus Maxentius. The root of the word is not listed anywhere, but I theorize that it derives from the word maximus, or "greatest". Fitting for a Roman emperor. If this is the case, the word is from Proto-Indo-European meghs ("great"), but it might not be. What we can take away from this, really, is that magenta has had armies and rulers alike lay claim to its etymons.

Pardon the terrible title pun that half of you won't get. The word avocado was coined in 1763 and referred to the relevant tree when it was brought into English. This was a loanword from Spanish, where the cognate avocado had the same definition, and that in turn is from the earlier term aguacate. This might suggest water (agua), but it's much more interesting than that: this stems (no pun intended) from the Nahuatl word ahuacatl, describing the fruit, specifically. This was a homonym whose secondary definition meant "testicle". Both terms come from the proto-Aztecan word pawa describing the fruit, but somewhere along the line a metaphorical meaning, possibly referring to the shape of the food, emerged. It is even possible that the term we have now comes from the "testicle" definition, but that is unlikely. The proto-Aztecan word probably is from the proto-Uto-Aztecan family, which is only theorized by linguists to exist.

A requested word, octopus seems pretty self-explanatory. In the eighteenth century, it was coined by Carolus Linnaeus as the genus name for that type of mollusk. This comes directly from the Greek word oktopous (surprising but not uncommon for Linnaeus, who favored Latin), which was itself a portmanteau of okto ("eight") and pous ("feet"). Okto is from Proto-Hellenic okto, from Proto-Indo-European oktow, which might itself stem from the earlier PIE word for "four" (since they counted on one hand, I suppose?), hokto. Meanwhile, pous was also developing from Proto-Indo-European, in this case from the root ped, or "to walk". Though this is outside the diachronic realm, I'd like to make a quick note about the pluralization of octopus: octopi is incorrect; it adds a Latin suffix to the Greek word. Though it's not really important, if you want accuracy, go for octopuses or octopodes.

It occurred to me that Europeans got cotton from the Arabs, so shouldn't the word be Arabic too? Turns out I was right! In Middle English, cotton was couton, and that came from the Anglo-Norman word coton. The word that passed through either French, Italian, or Spanish (there is no agreement among linguists there) to come back to the Arabic word qutn, still with the current definition. Through local dialects, qutn can be traced to the Egyptian root qtn (no vowels in Ancient Egyptian, remember), still meaning "cotton". The lack of semantic change is obvious; the word always described that crop, which has been around almost as long as language has. Etymologists struggle going further, but it is theorized that it can be traced to an Akkadian word that meant "flax" or "linen". If true, this descended from East Semitic and is ultimately from Afro-Asiatic.

You all know what a caret is, but only few of you know the word for it. A caret is the carrot-shaped symbol used to denote exponents or to make editorial changes (^), not to be confused with a circumflex. Since the caret was used for the latter purpose much longer than the former, the word comes from the Latin term caret, or "there is lacking". When a caret was added to put in more words, that statement was acknowledged as implied. This is a conjugated form of carere, or "to lack", which reportedly stems from the Proto-Italic cognate kazeo, ultimately from the familiar Proto-Indo-European root kes, or "to cut". The aforementioned Latin word carere, by the way, is also the source of the word caste, through castus, "separate in a pure way". The word caret should also not be confused with the caret package, a programming term which is the acronym for Classification and Regression Training. Those last two facts should've been added by caret.

In near-primordial times, when Proto-Indo-European was spoken in the majority of Europe, the primitive word men emerged. It is not by the current definition you know today; it's not even connected. Rather, it meant "to think" and gradually became standardized, by troglodytian terms. This eventually splintered into the Proto-Italic word moneo, which meant "warning", an understandable change in definition. This passed into Latin as "advise", and a conjugated form of that was moneta, or "advisor". This was then used as a title of respect for the Roman version of the Greek goddess Hera, Juno Moneta (literally: "Juno the advisor"). The Romans crafted a lot of their coins in the temples of the gods, especially Hera's, so moneta metynomically got applied to "money". This later became the French word monoie, which became the English word money, both with the current definition. If you know any "financial" "advisors", please laugh now.

The word laser was coined in 1960, and before then it wasn't one word at all. It was five: laser is actually an acronym, that of Light Amplification by the Stimulated Emission of Radiation. People liked the futuristic feel of the term, and it caught on quickly (word usage was more than two hundred-fold greater in 1998 than in 1958). But the plot thickens! The whole idea of the acronym was influenced by another relatively recent neologism, that of maser. You might not recognize it, but it's utilized in microwave technology and is a compound of Microwave Amplification by the Stimulated Emission of Radiation. Indeed, a "laser" was originally an "optical maser", until people figured out that they can switch things around. Laser's career was not over, however: it had yet to influence an acronym itself! The word taser was an acronym of Thomas A. Swift's Electric Rifle. This obviously overuses the power of acronymization, but it was both influenced by laser and by the actual rifle of Thomas Swift in a 1910 novel by Edward Stratemeyer. Don't be fooled by these three words, though: a lot of etymologies see people claiming them to be acronyms and they in fact are not.

|

AUTHORHello! I'm Adam Aleksic. I have a linguistics degree from Harvard University, where I co-founded the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society and wrote my thesis on Serbo-Croatian language policy. In addition to etymology, I also really enjoy traveling, trivia, philosophy, board games, conlanging, and art history.

Archives

December 2023

TAGS |