|

Ambidextrous (a word request) is, as many know, the ability to use both hands with equal adeptness. But the implications of the word are not upheld by its etymology. The ambi- prefix of the word can be followed back to the Proto-Indo-European word ambhi, which meant "around". This went into Latin as ambi "around", which later changed over time to be defined as "both". The dextrous part of the word is a combination of the suffix -ous and the word dexter, which meant "right-handed". This came from PIE and the root deks, or "of the right hand". That's right; ambidextrous originally meant "having two right hands". This was figurative, of course. It's impossible to have two right hands; one would always be on the left. I don't know why I'm clarifying this. The logic behind the word is that most people were more skilled using their right hand, so that became generally known as the "able" hand. Ergo ambidextrous really meant "two able hands". A curious and lesser-known antonym of ambidextrous is ambisinistrous, which meant "two left hands" in the same sense that ambidextrous meant "two right hands". And, yes, this is related to the word sinister, as are all things concerning the left (my apologies to Democrats).

0 Comments

I couldn't resist; I had to do another element. Cobalt (Co) has one of the most fascinating etymologies on the Periodic Table. it can be traced back to the German word kobold, meaning "goblin". How did this transition occur? As German miners in the thirteenth century were sifting through rocks containing Cobalt, Arsenic, and Sulfur, they noticed that they got sick whenever they worked with this deadly combination. Superstitious as medieval peasants were, these German goofballs assumed that their work was cursed by goblins, or to use their word for it, kobolds (this is at this point also an English word. It's pretty rare though, and is basically a lesser-known synonym for goblin). Through the wornderful word of metynomy, since the rock was associated with kobolds, it became known as a kobold itself. This word hopped around in Germanic, became cobalt the color, became exclusively referred to concerning the actual Cobalt portion of the ore, and eventually got landed between much more serious words like Uranium and Molybdenum. Kobold as a word in German literally meant "house-goblin", from the words kobe "hut" (I couldn't trace the etymology of this bugger) and holt "goblin" (from hold "friendly in a troublemaking way", which in turn came from PIE kel "to tend", after a brief stint in Proto-Germanic)

The word sugar has done a complete pivot in direction, concerning its definition. Originally, it came from the French word sucre, which came from the older French word cucre, which came from the Latin word succharam, which came from the Arabic word sukkar (where we get Spanish azucar from), which came from the Persian word shakar. At this point, all the way you trace it back, to about 600 CE, this foud noun still had the same meaning and generally followed the path that sugar itself came to Europe. Then it got interesting. Etymologists agree that this can be further traced back to the Sanskrit term for "sugar", sharkara. However, this word did not originally mean "sugar". In fact, its definition was "gravel, grit, or dirt", which because of sugar's texture, was attributed to the white stuff itself (that being sugar). Thus a complete turnaround occurred, from grey, yucky grit to white, tasty saccharine powder (saccharine also came from the Sanskrit word). Some of my sources identify this as the offspring of the Proto-Indo-European word korkeh, "gravel or boulder". But wait! It may not be from PIE! A researcher for the National Center for Biotechnology Information identified the etymology as coming from the Chinese word sha-che, "sugar", completely bypassing the gravel theory. Though the other is more logical, this is an interesting alternate theory...

This is a little sneak peak of my upcoming infographic! I had to include the etymology of argon because it's so fascinating and I want to explain it more. My usual sources, and many etymologists, disagree on this subject. All of them do concur that it stems from the Greek word argon, a neuter of argos, meaning "lazy". This makes sense, because as a noble gas, argon interacts very little and is therefore "lazy". This is where the opinions diverge. The theory I am partial to is that this can be traced back to the Ancient Greek word ergon, "work", which along with the prefix a- would mean "not working". This theory would trace back to the PIE word werg, translated as "to do" (obviously the forerunner of today's word work and somehow that of organ). The second school of thought trace this to an older word, argos, which was defined as "bright" (and this supposedly makes sense because no one would work if it was bright out? I like the other idea better; and it's more whimsical). This word, which definitely existed, came from PIE herg, or "white". A third, loony idea, connects this to Proto-Georgian and the Mingrellian root egr, concerning that which no one can figure out. Most mysterious!

If you ever feel confused about how to spell that Jewish holiday around Christmastime, I don't blame you. There are multiple correct spellings, and multiple factions will try and correct you on this. Aside from Hanukkah and Chanukah, you also may also see spellings like Channuka, Channukah, Chanuca, Chanuccah, Chanuka, Chanukka, Channukkah, Chanuko, Hannuka, Hannukah, Hanuka, Hanukka, and Khanukah. You should probably stick with the first two, though. The reason for all this confusion is the hard-to-translate Hebrew alphabet, from whence the word(s) came. Since it's composed of all-consonant, non-Latinized characters, linguists have a devil of a time trying to sort out what is the correct spelling, leading to several kippah-kindled kerfluffles and all these variant spellings. The limited etymology of this word, however, is quite different from the spellings in that it's mostly agreed upon (apart from the transliterated spellings, of course). The Festival of Lights rougly comes from the Hebrew word khanuka, meaning "dedication". This was conjugated from khanakh, "to dedicate". This came (even more roughly) from kinekh, or "to educate", since educators dedicated their lives to teaching. Since this is such an old language, we really have no clue what happened before that, only that the word had the consonants h, n, and k.

It's the day after Christmas (at least when I'm writing this), and the malls are undoubtedly full of disgruntled shoppers like yourself waiting to return those Smurf parasols. What was Uncle Frank thinking? As you go about your business today, bear in mind the etymology of return; it's a little something to keep you sane during the hassle. The first time return meant "something sent back" was in the nineteenth century, but the word itself has stuck around since the fifteenth century, and is obviously a combination of the prefix re- and the word turn. Since Roman times, the prefix re- has always been translated as something along the lines of "again". However, the etymology of turn is much more in-depth. In Old English, it may be traced back to turnian "to rotate or revolve", where neither spelling nor definiton hace deviated too much. This came from the French word tourner, which denoted the action of turning something on a lathe (a turning thing used to cut stuff). This went through Latin and Greek as tornus and tornos, respectively, which both meant lathe and caused the verb through the wonderful art of metynomy. The Greeks had to get this word from somewhere, so they filched it from PIE and the word tere, which could be defined as "to rub", since when something is put on a lathe, it is rubbed against the blade. Tere is also the progenitor of today's common word throw; just a fun fact.

The etymology of Christmas is unsurprising, though it had to be done today. Christmas is a combination of the Old English words Cristes and mæsse, which meant "Christ" and "mass", respectively (the latter in the biblical sense). Cristes comes from the Greek word khristos, which translated as "messiah" and had Hebrew origins. This went into Latin as christus and English as crist, and though it was originally just a title almost everybody thinks it was his last name. It's not; he had none. Mass did come from PIE, where it can be traced back to the word meith, which meant "to remove". This became the Latin word mittere, or "to send away", and this in turn was conjugated into Latin missa, with the defintion of "dismissal". Eventually this became mass, through some variations, including messa and maesse, with a significant definition change. The transition from "dismiss" to "mass" occurred because at a mass you would "send" or "dismiss" your prayers to God. It 's kind of funny, really, since the mass part of Christmas originally meant remove, and when you're saying Christmas, you're celebrating the Saviour a lot less than you're asking for his removal.

If you ever refer to an eve as the day before an event, such as "Christmas Eve", etymologically speaking you are grammatically incorrect. Eve dates all the way back to Proto-Germanic (but not PIE? What a slacker) and the word aebando, which basically was a synonym of even, though that came from a slightly different root. As Proto-Germanic became Old English, aebando became aefen. This then became aefe because of rampant misspellings, and eve, since ae sounds like e, and f sounds like v in many cases. This changed definition from "even", because like the word equinox, it was meant to describe a period evenly split between day and night. The whole "evening" definition was later modified to mean "evening or a day before an event", so don't worry, because today you are grammatically correct. Fun fact: the name Eve has nothing to do with this Germanic nonsense and came from no-nonsense Hebrew, literally meaning "a living being".

The roots of cathedral has been around longer than cathedrals have, which is saying something. This word, meaning "main church of a diocese," dates all the way to the Proto-Indo-European word kmt, defined as "down" or "with". This went into Greek as kata, solely with the meaning "down", and soon fused with another word (hedra, from the PIE root sed, "to sit") to make the word kathedra "seat or bench", since you sit down on a seat. In Greek-to-Latin transitions, k's often change to c's, and this was no different, as the word cathedra took place (this doubled as a "comfy seat" or a "woman sitting in a comfy seat"). As this passed into Church Latin, it dropped any possibly inappropriate connotations as cathedralis or "bishop's seat". This makes sense if you view "seat" as a "seat of power" and a cathedral as a seat of a bishop's power, which in most cases it is. So, next time you sit down in a cathedral, you sit down in a sit down.

I found this words as I was trawling through debunked etymology myths on snopes.com. The word blackmail seems like it would make sense if it were simply a combination of black (which was basically a synonym for evil back in the days) and mail, as in missives. This is not the case, for the latter, at least. As you may recall from my first ever post, the word black came from the Germanic word for "fire", which came from the PIE word for "burnt". The mail part also traces back to PIE, as mod, "to meet or assemble". This went into Proto-Germanic as mothla and Gothic as mapl, or "meeting place", kind of a metynomic shift (a metynomic shift is when something takes on the meaning of something previously associated with the former) and this became maedel in Old English, undergoing a double metynomic shift to mean "meeting" or "council". This then became mal, or "lawsuit" and male meaning "tribute". This, combined with black, utilized a sort of different spelling, and meant "evil tribute", and had nothing to do with "evil mail".

Sorry for the depressing title, but today is the darkest day of the year. The word equinox (which is not what we are in, we're in the solstice, but I did this word just for giggles) entered the English language in the fifteenth century, and came from the twelfth century french word equinoce. This comes from Medieval Latin equinoxium, which came from some older version of Latin and the word aequinoctium, literally meaning "the equality of night and day" and a portmanteau of the Latin words for "night" and "equal". The Latin word aequalis, meaning "uniform or identical" came from the older word aequus, defined as "flat or level", since things that are on level ground are equal. Aequus has uncertain origins past that, but the Latin word for "night" goes all the way back to PIE, and the word newkt, with the current definition. As PIE dissolved into a hodgepodge of otherwise unrelated language families, newkt went into Latin as nox (also the spell to turn your wand-light off in the Harry Potter books). Noctium could be used to describe nox the night, and is also present in today's words nocturnal and equinox (the -nox suffix is from noctium, not nox, just to clarify). It is thus that equinox literally translates into "flat night", if you trace back the word far enough.

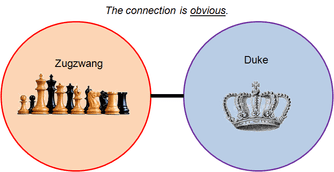

Hardcore fanatics of the game of chess such as myself will recognize the term zugzwang, which is when one is forced to make a move that is unsatisfactory. Little do these connoisseurs know that the word has royal origins. Zugzwang comes from its German cognate, literally meaning "compulsion to move". This comes from Old German ziohan, meaning "to pull", because yo move a piece you would pull it. Ziohan comes from Proto-Germanic teuhan, which in turn comes from PIE deuk, or "to lead", because those who lead pull their armies in to battle and whatnot. Hold up! Does deuk sound familiar? It should; it's the progenitor of today's word duke, a division of royalty (like earl and viceroy, et cetera). In Late Latin ducere meant "to lead", just like the PIE word, and from it spawned the word dux, meanig "leader or commander", which makes sense if you think about it, since leaders and commanders obviously lead their armies, "pulling" them into battle. The word dux later became the French word for "prince" duc, which later passed into English. Therefore the words duke and zugzwang, which only have one letter in common and completely different definitions, are etymologically correlated.

The word syzygy is not one known to many people, but it is definitely one of the coolest words in the dictionary. An almost impossible combination of all consonants, syzygy describes the astronomical phenomenon when three celestial bodies align or, in some circumstances, it can describe two alike things. Etymologically speaking, this came into English in the middle of the seventeenth century as "conjunction or opposition", from Latin syzygia, which came from its Greek cognate, but differed in definition; the Greek syzygia described a union of two animals, or the action of uniting two animals through means of yoking them. This, in turn, was a syzygy of the two words syn, meaning "together" (from Proto-Indo-European ksun, "with") and the Greek word zygon, meaning "yoke" (this came from PIE yeug,"to join", which is the father of today's words jugular, yoga, and zygote). The definition changed from "to yoke animals together" to "alignment of space-y stuff" because to yoke two animals is to join them, and the planets are likewise joined when the syzygy is formed. Etymology is awesome!

The word bucket has been around for a while in the English language, and like many other English words, traces back to Proto-Indo-European. Apparently bucket can be tentatively traced back to the word bhel, meaning "swell"; also the root of today's words bull and boulder. While the definitions of the latter two may make more sense to an outsider of etymology, it actually makes sense how "grow in size" became "large can with a big hole". As bhel became bheu, which became buh in Proto-Germanic, the definition changed to "belly", because of the tendency of bellies to grow (incidentally, the word belly did worm its way through the same root). As the Germanic languages became the English language, the word buc took place, not a huge change in spelling, but a tremendous change in definition: for this new word meant "large pitcher". It sort of makes sense because the belly is essentially a large pitcher for food and water, and pitchers can be bulbous in the same manner as stomachs can. This English word buc went into French as buquet, and then back into English (etymology is awesome!) as bucket, eventually meaning "a different kind of pitcher". The colloquialism kick the bucket actually used to be a euphemism for suicide, because when you wanted to hang yourself you would kick out the bucket you were standing on. Gruesome!

I was delighted to find that this word I simply stumbled upon in search of my next post did not have European roots, the first on this site like it. The word tycoon, defined as "a wealthy person", actually came from Japanese and has a very peculiar origin. The first appearance of this word was in the Chinese dialect of Shinjing, where it meant "big" and probably sounded something like da. This passed into Chinese as the word tai, and meant "great or eminent". Around the same time, the word kiun also showed up, meaning "lord". These two words were not connected at all until the Japanese took them, put them together, and created taikun, a title meaning "great prince or leader". This was an actual term used to describe the shogun of Japan for a couple hundred years until those darn Americans came to unlock trade rights with Japan. There, the secretary of Abraham Lincoln, John Hay, took the word and used it in 1861 to describe the Republican president, since he too was considered a "great leader" by many. A few spelling altercations and taikun became tycoon, but it didn't start to refer to wealthy people until the 1920s, when many leaders were also fabulously wealthy, so "wealth" became equal to "power" until the "power" part was dropped completely for no reason at all.

The word hell is curious in its origin because of its now nonchalant relatives. This word for "fiery place of damnation" came from Proto-Indo-European, where it was the word kel, meaning "to cover or conceal". This also gave us our word for cell (both types), hollow, and hole, which all kind of make sense in retrospect. In the Proto-Germanic language, this became halja, or "one who hides something", which later became haljo, with the definition "the underworld", since the gods hid hell from mortals, ergo hell had both definitions for a while until it became exclusive to "damnation". If you studied Norse mythology, you would already be anticipating this next step, Hel. This simultaneously was the name of the goddess who controlled the bad underworld as well as the underworld itself. This passed from those Nordic languages into Old English, where hell underwent a series of mutations, from helle back to hel and then to hell; those old English monks liked to play around with spelling a lot. Hell went through a stretch of time where it was considered a curse word in the nineteen hundreds (it still is by some now) because of the connection to Catholocism those eager English Christians made.

Yet another requested word, audacity has a curious back story. Currently meaning "bold to the point of disrespectfulness", the farthest back it can be traced to is in Proto-Italic awideo, meaning "greedy". Thus you can see neither the definition nor the spelling has deviated in abnormal quantities from the original, a curious occurrence and all the more interesting in the world of etymology. After these primordial languages condensed into Latin, the word audacia was created, meaning "daring" or "bold". This was modified into the word audace "boldness", which eventually became French audacieux. I would like to take a second to note the etymological transition from a pejorative sense in the original proto-language to a linguistically positive meaning; from greedy to brave. This would soon take another sharp swing back to the negative with the English word audacity (and meant to describe the annoying, Harry Potter-like quality of being too brave, to the point of irritation), a full circle from "greedy" to "brave" and back to "disrespectful".

Another word request, and a fun one to do! Far before Engles and Marx popularized the word proletariat, making it near synonymous with communism, it has quite a different meaning. The farthest back it can be traced is to Proto-Indo-European, where it was proal, or "grow forth". In Latin this eventually got picked up as proles, and it actually meant "children" or "offspring" (today the precursor of progeny and prolific). In a later, special edition double-Latinized word, the Romans tacked on the ending -ian (a suffix talking about a person, with a much more boring history but also from PIE) to make proletarian. This is an actual word which still exists today, so naturally it wasn't difficult for this to pass into French as prolétariat, which described a group of people who were lower class, a definition already in place from the Romans, who loved taking nice words and making them mean. This then became the English word proletariat in the 1850s, became associated with communism only a few years later, and lived happily ever after.

Psychology, or the scientific study of the human mind, is well known to have Greek origins, but let's delve a little bit further. Though the first psychologist, Wilhem Wundt, didn't show up until the late 1800s, the word psychology was first coined in the middle of the seventeenth century. It was an English modification of Latin psychologia, "the study of the soul", and definitely came from the Greek stem psykhe, which doubled as "soul" and "breath", since the Greeks believed those two to be interrelated. This was named after the goddess Psykhe, the beautiful goddess of the soul married to Eros (the Greek version of Cupid). This goddess' name, in turn, stems from Proto-Indo-European, where the speakers used bhes to mean "breath or to blow". The -ology suffix is pretty common in science, coming from PIE leg, "to collect", through Greek logos and finally -logia, which was twisted around a little as it passed through two or three languages over three thousand years until -ology came into being. Through the ages, psychology directly had connections to the soul until it was finally used in an empirical sense to decribe the science of the mind (which according to the Greeks, was connected to the soul!). Technically, whenever you say "psychology", you're passing on the Proto-Indo-European ancestors and saying "collect your breath".

Another word request, though I thought its origin fairly obvious. Turns out, is isn't as straightforward as all that. Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious is a 34-letter word many may know from the 1964 Disney film Mary Poppins. It apparently is a nonsensical word supposed to describe feelings of extreme happiness or glee, and most people think the story stops there. However, Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious has been around much longer than the movie, and actually is a modification on the title of a 1940s song titled Supercalafajalistickespialadojus. This has some etymological sense, but not much. For example, the superlative super clearly adds a cheerful, happy ring to the word (dating back from PIE uper "over" through Latin). The word espial means "watching someone without being seen" but that's definitely not a root (though it invokes thought of the word special, which would make sense in the word). Most likely everything except for super is gibberish, despite some myths you can find online.

The word anecdote, essentially defined as "a funny little story you tell to break that awkward silence", has fascinating origins and a surprising change of definition. The farthest back it can be traced is to Proto-Indo-European do, or "to give". This roughly transitioned into Ancient Greek as didonai, still meaning "to give". In a conjugated form this could be written as dotos. The Greeks then tacked on two more things, their word ek, meaning "out", and the prefix an-, meaning "not". And so the word anekdotos was created, literally meaning "not give out" but taking on a definition in literary terms, "not publishing" a book or work. This later passed into French, with Medieval Latin influences, as anecdote, "a collection of secret or private stories," a momentous change in the word's history, though the transition is understandable. Later, as the word became English, anecdote was still a private story, but no longer secret.

Another round vegetable, pumpkin also dates all the way back to PIE. In those halcyon days of yore, pumpkin meant "to cook" and was spelled pekw (also the forefather of today's word cook). This then went to Ancient Greek as peptein "to cook". This eventually gave way to another Greek word, pepon, or "melon", supposedly because this cucurbit (a word meaning "of the melon family") was "cooked by the sun". The Greeks then happily used this word for about five hundred more years until its history was rudely hijacked by those darn Romans. Greek peopon therefore became peponem, which after Latin disintigrated, became French pompon, still with the definiton of "melon" and possibly the origin of a cheerleader's pompom. When this diffused into English as pumpion, it meant "melon or pumpkin" and as it became pumpkin, its definiton solidified as well. The word pumpkin, which was finalized in the seventeenth century, is also the father of many colloqualisms and expressions in our language. Pumpkin as a term of endearment probably meant from "round, cute child", pumpkin-head suggested that you had "goop for brains" and pumpkin pie developed as the delicacy did. Lastly, I just would like to recap and point out that when you say you're "cooking pumpkin pie" you're actually "cooking cooking pie."

When you say "head of cabbage", you're actually saying "head of head". This dates back to the Proto-Indo-European word kaput, meaning "head" (also the source of decapitate, capital, and the aforementioned chattel and cattle). In Latin, this became caput (this was additionally used in the first Harry Potter book as a Gryffindor password, caput draconis or "dragon's head"). Eventually, as Latin died out (effectively) and the word passed into French as caboce, then caboche later, still with the definition "head". At this point in Middle French, caboche eventually transitioned fully into the definition "cabbage", due to colloquial terms that compared the vegetable to the shape and size of a human head. A similar occurrence was underway in Italy at the same time; apparently the similarity was uncanny back then. Though the definition was now what it currently is, caboche still had some changes to undergo. As many French words did, this one snuck into the English vernacular, as caboge, in the middle of the fifteenth century. Due to bad spelling, poets trying to be fancy, and literary errors, this eventually phased into the spelling cabbage, with the same pronunciation.

Another word request. Sophomore actually has one of the coolest etymologies I've ever seen. It's broken up into two words, both stemming from Greek. The first of these, sophos, was a Greek word primarily meaning "clever" but in this case meaning "wise". This is the same root from which we get today's word "sophisticated". However, the second part of sophomore, the (in this case) suffix -more, came all the way from the Greek word moros. This meant "fool" or "idiot" and is also the root of the word "moron" today. Sophomore was spelled sophumer when it was used in the seventeenth century, but the spelling has evolved over time. The definition, "in second year of high school or college", though, has remained constant, a striking change from the original meaning. Now, you may still be scratching your head about the oxymoron I dropped, then digressed from so offhandedly two sentences ago. Sophomore is indeed a portmanteau of a word meaning "stupid" and a word meaning "smart". It described the tendency of adolescents to behave so irrationally despite thinking rationally sometimes. Etymology is so amazing!!!

A requested word! Manifesto, meaning "a public declaration of political ideas," actually used to mean "to apprehend". The farthest back it can be traced is the Proto-Indo-European word man, meaning "hand". You can see how this appears unchanged in the prefix of the name, but it's actually gone through quite a couple alterations. It Latin this word eventually became manus, "that of the hand" or "strength". As Latin aged, a bunch of words were combined randomly to make more complicated words, and someone along the line created manifestus, a combination of manus and festus, which meant "struck". Thus manifestus became "hand-struck." Eventually its definition transitioned to mean "apprehended," because one who was "apprehended" was "struck by a hand". When one is apprehended, one usually confesses, so the truth can come from being apprehended. Because of these connections, manifestus changed from "hand-struck" to mean "elucidate or make clear". As many Latin words did, this stayed in the area to become the Italian term manifesto, now describing the handy, striking, and elucidating declarations of a political party. This eventually passed into English, with the same definition and spelling.

|

AUTHORHello! I'm Adam Aleksic. I have a linguistics degree from Harvard University, where I co-founded the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society and wrote my thesis on Serbo-Croatian language policy. In addition to etymology, I also really enjoy traveling, trivia, philosophy, board games, conlanging, and art history.

Archives

December 2023

TAGS |