|

Loosely defined, a Schwarzschild radius is a point where a sphere is forced to become a black hole. The term Schwarschild is a portmanteau of two German words: Schwarz, meaning "black", and schild, meaning "shield", which makes sense. Schwarz, through Middle German swarz, Old High German swarz, and Proto-Germanic swartaz, comes from the Proto-Indo-European root swordo, meaning "black". Very little semantic change for that term. Schild, through Middle German schilt and Old High German scilt, comes from the Proto-Germanic word skelduz, which also meant "shield" and is the etymon of the English word shield, by way of the Old English word scild. Skelduz is from Proto-Indo-European skel, which meant "to cut", under the connection that you cut wood to make a shield. So, now we know how Schwarzschild came to mean "black shield". HOWEVER, that was all just the last name of Karl Schwarzschild, a German physicist who first theorized the radius. This may be the single most incredible coincidence in all of scientific etymology and is amazing

0 Comments

You know how the President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, appointed his wife to be vice president last February? No? Well, anyway, that was an example of nepotism, the act of favoring friends or relatives with political positions. However, in the olden days, it was just family, and before that it was just nephews (so Aliyev never really was nepotistic). This is because of the word's interesting etymology: through French nepotisme and Italian nepotismo, the word derives from Latin nepos, meaning "nephew". This is because the popes of the Middle Ages (situated in Italy, of course) commonly appointed their own nephews to serve as cardinals, most notably Paul III and Callixtus III. Anyway, nepos (also the source of nephew, through French neveu) derives from the Proto-Italic root nepots, from Proto-Indo-European nepots, which carried a double meaning of "nephew" and "grandson". I wonder if this would hold up as a legal loophole...

A comptoller, a type of elected financial officer, pretty obviously comes from the word controller. The catch here is that it's a mistake: folk etymology altered the title from controller (which in the old times, was always financial) to comptroller under the influence of the French word compte, which meant "account", the kind of thing comptrollers deal with. They changed this because they thought it to be correct, never stopping to think of the root control in the word, which means that it was idiotically and accidentally altered. Now, the verb control comes from the Old French term contrerole, which meant "register", because of that's where your assets that are controlled by the bank are held. Before that, it derived from Latin contrarotula, literally meaning "against wheel" because those registers would have a little wheel in them. Contra ("against") is ironically from com-, which meant "with", from the PIE root kom, meaning "beside". Rotula ("wheel" or occasionally "roll") is from the simpler form rota, from Proto-Indo-European hret, which meant "to roll", as a verb. Make sure comptrollers don't control your rolls of money, or we'll be in an etymological cycle with no way to escape.

Your whole life, you've probably been wondering why the word colonel sounds like kernel, but have been too afraid to question it. That's basically the story of how we got the word. We used to have a term, coronel, which was pronounced as you might think. This was slurred to omit the second o later, but that happens to words all the time. The clincher here is that the word's spelling spelling naturally evolved, but people didn't change the pronunciation in fear that it would be wrong. And now it is. However, earlier on, this came from the Middle French word coronnel, which quite ironically traces to the Old Italian word colonello, giving us a loop back to the l spelling which is quite unnecessary. Colonello is from Latin columna, which meant "pillar", under the correlation that a military commander organizes his soldiers into a column, and another word for column is "pillar". Through Proto-Italic kolamen, this goes to the Proto-Indo-European root kelh, which meant "to rise" (since pillars rise). Side note: the French have since modified coronnel to colonel as well, but the French were wise enough to change the pronunciation too, so they have an l in it and we don't. In Spanish, coronel is pronounced as you may think and is a remnant from the Middle French variation.

You read that title right, and probably guessed its significance. The word Cajun comes from the word Acadian. The demonym for a multicultural people group in Louisiana comes from a word describing a woodsy region in eastern Canada. How? To explain, let's use history! When the British colonized the Acadian region in 1710, the people there were already loyal to France, so when the French and Indian War came about, Great Britain deported Acadian residents en masse to the thirteen colonies so as to neutralize a war threat. Those Acadian migrants eventually traveled further south to French-friendly territory and found themselves in French Louisiana. Subsequently, they settled down to create that characteristic culture we know today. The name changed because the French called Acadians Cadians, and the Acadian accent slurs ds into more of a j sound, so we ended up with Cajuns. Now, Acadia as a region gets its name from Italian Arcadia, a latinization of the Greek region arkadia, which is named after Arkas, the mythical descendent of Zeus who founded the place. If we are to go even further, my research indicates (though it is likely that this is erroneous) that Arkas is likely a Turkish name, Arkadas, which is a portmanteau of arka, meaning "back", and das, meaning "fellow". These are Proto-Turkic in origin, but tracing it even more just gets redundant and obfuscating. Now, though, you have a great idea of how convoluted good etymologies can get!

You might've heard of Silesia, that area in central Europe that's questionably German, or Czech, or Polish, depending on who you ask. It was important during the 1700s, at least. Anyway, that region's name is the origin of the word sleazy! They were making cheap and flimsy clothing which merely imitated high-quality textiles and exporting it all across Europe. Subsequently, Silesia was modified to sleazy, and the "flimsy" meaning naturally evolved to be more like "amoral". Going backwards now, Silesia is probably from a German word sounding like Schliesen, a name of a local mountain, from Silingi, the appellation for a Vandalic people-group who lived near that mountain. Since those people were Germanic, and the word sounds Germanic, I'm guessing that word comes from Proto-Germanic, though we don't really know for sure.

The word fail comes to us through Middle English failen, through Anglo-Norman failir, from the Old French word falir, which meant "to make a mistake". This is not too big of a change from today, but is important as we trace the term further to Latin fallere, which meant "to trip", since tripping is a mistake. Earlier, that meant "to cause to fall", and it's from the Proto-Indo-European root bhal, "to deceive". This makes sense as deception can also lead to tripping, which causes falls. All right, rewind for a second. You might have noticed that fallere sounds the word "fall" and also means "fall". Is there a connection? Nope! Fall, through Old English feallan and Proto-Germanic fallana, traces to a Proto-Indo-European root sounding like pol and actually meaning "fall" for real this time (also the root of the synonym for "autumn"). Not a fail.

We work with manila folders and manila paper all the time, but have we ever considered why the name of these office supplies sounds like the capital of the Philippines? Turns out that is in fact where it comes from! You see, that characteristic buff, stiff paper comes from manila hemp, from the abacá plant native to Luzon. Thus your manila envelopes were directly named after the capital of the Philippines. But where does Manila, the city name, come from? The answer is the Togalog name Maynila, also describing the metropolis. This in turn is a portmanteau of may (meaning "there is") and nilad (meaning a type of indigo plant, though some discredit this as a myth). Together, this means "there is indigo". Nobody's really sure about nilad, but both words probably come from Proto-Philippine, and, by extension, Austronesian, poorly researched Asian languages that they were.

Golly, my flag infographic didn't do the chevron justice, so I simply had to expand upon it here. Currently describing a V-shaped pattern, often used in military or heraldic applications, the chevron in Middle French meant "rafter", because of the angle in roofing which is similar to the chevron. This, even more shockingly, comes from the Latin word caper, meaning "goat" (normally a male), a transition that occurred allegedly because the bent hind leg of a goat was similar in angle to a rafter. More likely than not, caper traces through Proto-Italic to the Proto-Indo-European root kapros, meaning "male goat" again. All of this just goes to show that etymology can take quite interesting and illogical turns whenever it feels like it, spanning completely contrary and bizarre definitions to itself. The word chevron has been steadily decreasing in usage since the late eighteenth century.

If we were to go back in time about 6,500 years ago, we would encounter the Proto-Indo-European root ne, which meant "not", and another root, wekti, which meant "thing". Fast forward 5,000 years, and these two terms made their way through Proto-Germanic to become the Old English word nawiht, literally meaning "not a thing", or "nothing". This went into Middle English as naht, nought, and naught, all of which meant "nothing" as well. You'll recognize that last spelling as one that has survived to today, but wait, there's more! In the late 1300s, a -y was attached to naught to create a new word meaning "poor" or, literally, "having nothing". Later, rich and snobby people changed the definition to "lawless" and "malignant", because of the perceived connection between poverty and crime (for a similar example, see the etymology of villain). Over time, the meaning mellowed a bit, and that's how we have our modern word naughty.

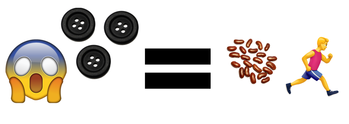

Koumpounophobia is the irrational fear of buttons. That's all you need to know about that; on to the etymology! The root appears to be koumpono, which is Greek for "button". As most Greek words do, koumpono traces to Ancient Greek, but people in Ancient Greece wore tunics and did not have buttons. Instead, the modern Greeks decided that their newfangled clothing item looked like a bean, so they borrowed the Ancient Greek word kuamos, which meant "bean". Further origins of this get hazier and hazier, so to avoid inaccuracy, let's just digress to the suffix -phobia, which is well known (Wikipedia lists 187; there are countless beyond that). This is from Greek phobos, which meant "fear" and was also the god of fear, from Proto-Hellenic phegwomai, from Proto-Indo-European bhegw, which meant "run", under the connection that you run from fear. So koumpounophobia, the fear of buttons, really is just running from beans.

When they first discovered that Australian curiosity of a mammal, scientists wanted platypus to be its genus name, but that was already taken up by a kind of boring beetle, so they kept platypus as a colloquial name and used ornithorhyncus for the genus name instead. Both the beetle and the mammal name mean "flat footed" and derive from the Ancient Greek word platupous, which itself is a portmanteau of platys, a word meaning "flat", and pous, a word meaning "foot". The former can be traced to the Proto-Indo-European root pele or pelh or plat or pleh (I have seen it in so many variations at this point, for it is quite a common root), all of which also meant "flat", and pous is a formation from ped, "foot", itself deriving from the Proto-Indo-European root pod, which also meant "foot". So, even if we haven't seen much semantic change, we at least now known that platypodes can't serve in the army. Oh, yeah, platypodes, not platypuses, or, God forbid, platypi.

When you're playing off some sheet music on a piano, and it tells you to play piano, any musician can tell you that it means quietly, not (quite redundantly) on the instrument you're already using. So it would be a logical conjecture to conclude that the piano instrument comes from the level of volume piano, right? Well, kind of. It actually comes from the Italian word pianoforte, which meant "soft yet strong", because of the large range of sounds a piano can make. The "soft" meaning is indeed in the prefix part, piano, but now it is evident that that is not where the word comes from directly. Through Latin planus, "even", piano traces to the Proto-Indo-European term pele, "flat", which is also surprising, but makes sense when you consider that the term just got more figurative over time. Meanwhile, forte, another measure of sound in music, meant "loud" or "strong", also got more figurative through the ages, developing from Latin fortis, which meant "fortress", from PIE bergh, "to rise". So pianoforte, and by extension, a piano, really means "rising flat" or "even fortress". Music is so complicated.

Right now, the word quagmire means "a boggy area". However, it's developing a definition of "complex or messy situation" that will probably overtake the former in definition pretty soon. The exodus has already begun. Despite all that etymology in action, at its most literal, quagmire is a tautology, literally meaning "marsh marsh" in Old English. How? Well, quag is an obsolete word that meant "bog", from Middle English quabbe, "marsh", ultimately from Old English cwabba, which meant "to tremble", like mushy ground does underfoot. Further origins are unknown. Meanwhile, mire is a slightly less obsolete word meaning "muddy area", From Middle English mire, meaning "swamp", from Old Norse myrr, also describing something like a "swamp" and deriving from Proto-Germanic miuzijo, which can eventually be reconstructed as a derivative of Proto-Indo-European meus, which meant "damp", an obvious connection. So, if we neglect the redundancy of this pointlessly stacked word, we can fully trace quagmire as meaning "damp tremble".

Every Thanksgiving season, we season our turkeys or just stay at home and watch a season of a crummy TV show. How did all these different definitions come about? The latter two come from the first; a TV season by connection of "a recurring event each year", and turkey seasoning is a bit more complex: it's correlated because of an earlier meaning of "ripe", and crops get ripe seasonally. But where does season come from? Well, through Middle English alterations such as seson and sesoun, it goes back to the Old French term seison, which meant "time of seeding", which makes sense because seeding and the harvest were the only important seasonal acts to anyone back then. As many French words do, this derives from Latin; in this case it's sationem, an accusative meaning "a sowing", from serere, "to sow", which in turn comes from the Proto-Indo-European root seh, with a definition of "to plant" or also just "to sow". Farming is the most seasonal act of all.

Frugal is yet another English word made up by Shakespeare. Well, he didn't make it up, per se, as much as use it for the first time in English (in Much Ado About Nothing). He got it, through Middle French frugal, from the Latin word frugalis, which meant "thrifty", not unlike today. Then it gets weird: frugalis is from the previous Latin word frux, which meant "fruit" but had several layers of figurative speech: it also meant "produce", as in producing fruits through hard work, and it also meant "success", because producing fruits was successful. However, one who is successful saves one's money, which is how we got landed with frugalis. Frux is from the Proto-Indo-European root bhruhg, which also meant "fruit" but could additionally mean "enjoy", under the premise that people enjoy fruits. I know, it's a quagmire. Also, since I'll never get a chance like this again, I'd like to point out that the word frugivore, meaning "a person who eats fruits" has its stem, frugi-, also trace to frux. Now you know!

When the Normans invaded England in 1066, they brought with them their word salarie, the precursor of salary, that which we all work toward. Through the Old French word salaire, this comes from the Latin term salarium, which also had a definition of "wage". However, far more shockingly, as we move backwards to salarius, it actually meant "of, or pertaining to, salt". How did this nigh-psychedelic transition occur? Well, etymologists think it's because the Roman army used to pay some of its soldiers in salt, which was a valuable commodity back then! So now we trace money to an ionic compound, but what came before that was the root sal, "salt". This seems to be from a cognate in Proto-Indo-European, a root which also sounded like sal and meant "salt", from whence our word salt derived (through Proto-Germanic saltom and Old English sealt). Next time, ask for your wages in NaCl, or even better, 1-butylpyridinium bromide.

Saying the phrase billiards cue is tautological, because a billiard in French referred to both the popular game "pool" and the stick used to play pool. That later definition is more important, for as we move back to the Old French word bille, it just means "stick". So, basically, a game of billiard is just a game of "sticks", which sort of makes sense. Earlier on, the word bille was much larger in size, actually meaning "tree trunk", from Latin billa, with the same meaning. This in turn is unknown in derivation, but etymologists theorize it is Gaulish in origin, which would geographically bring us back to France. It is thought that this is in fact Gaulish because Gaulish is a Celtic language, and there is a Proto-Celtic term sounding like belyos, which meant "tree" as well. In any case, the word jumped that obscure period and most likely ultimately comes from the Proto-Indo-European root bhleh, meaning "blossom", under the connection of another living plant.

The word canopy means a kind of "covering" today, but its real origin might "bug" you. we get it from the Old French word conope, through a previous version of canope. This meant "bed-curtain", not unlike our modern definition. Canope derives from the latin word canopeum, from the earlier Latin word conopeumm, which meant "mosquito curtain". This also makes sense, since in the olden times people would sleep with protective curtains around their beds to keep out those nasty little bloodsuckers. After Greek konopeion, once we delve down to konops, it gets much more interesting. This meant "mosquito" (the "mosquito net" definition was metonymically applied to the curtains later on), and comes from an Egyptian word that sounded like hams and meant "gnat" (the Greeks mistakenly interpreted that to mean "mosquito"). Basically, it was a complete mess. Whatever.

The word antebellum is used by historians to describe a period prior to a conflict, often the Civil War or the World Wars. This is from the Latin phrase ante bellum, which literally meant "before the war". Ante comes from Proto-Indo-European hent, which kind of meant "forward" (a reasonable connection to "before") but earlier meant "forehead" or "face" (a reasonable connection to "forward"). Meanwhile, bellum (the antecedent of bellicose, through bellicus, "of war") was modified from duellum (which, yes, is also the etymon of duel). Duellum, like ante and most other Latin words, also derives from Proto-Indo-European, in this case the reconstructed root dehw, which meant "to injure" or "destroy", or something like that. So, in a way, together, antebellum, far from preceding war, actually means "forehead destruction". What fun!

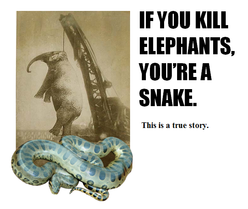

In 1916, the town of Erwin, Tennessee hanged an elephant named Mary who accidentally killed an inexperienced trainer. Yes, hanged. Technically the circus owner who approved the execution was an anaconda. Yes, anaconda. What is now a type of snake in South America was accidentally applied; the correct version was a snake in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon). This was picked up by British merchants from the locals, but the question is, which locals? In the olden days, there was a Tamil majority, and they used the word anaikkonda, which literally meant "having killed an elephant", referencing the great strength of their pythons. However, there was also a substantial Sinhalese population, which also had the word henacandaya, which literally meant "lightning stem". Both of these definitions are far stretches, but it must be one. Hopefully it's the former- then my anecdote's inclusion would be really justified.

We've seen that Lucifer means light-bringer, but now somebody requested the word Satan. While researching, I found the etymology to be fairly straightforward, but there were some interesting side Easter eggs! For example, did you know that Satan is actually a genus name for an ugly kind of fish? And that Lucifer should not be used interchangeably with Satan, for the former refers only to the angel before he fell, and vice versa for the latter? Anyway, onto the origin. Satan, through languages the Bible's been reprinted in, can be traced to Old English, Latin, and farthest back, Greek. This Greek Satan is from the Hebrew word satan (no capitalization) which just meant "adversary", a definition which makes sense. Due to a cognate in the other Semitic language of Arabic, linguists reconstruct this as from a root stn, again with the same meaning, and probably from Proto-Afroasiatic through Proto-Semitic. Really old words like this are hard to etymologize.

Today the word ludicrous (not ludacris, that's a rapper- but he did get his stage name from this word) is basically a synonym of ridiculous. But in the olden days, it got a bit more playful. As far as etymologists can tell, sometime in the early 1600s, it was borrowed in from the Latin word ludicrus, which meant "sportive"- here the jocosity from a sport slowly extended in meaning to a "fun time" to "laughter". Anyway, the nominative here is ludicrum, which, like that transition definition, meant "amusement" in general. This makes sense, because that is the transition between ludicrus and another Latin word, ludere, a verb meaning "to play". Ludere is from the Proto-Indo-European root leyd, which is theorized to mean "play" as well. It may seem ludicrous, but usage of ludicrous has been steadily decreasing over time; the word is slowly becoming archaic.

The word bridal has a lot more going on than you would expect. Now, of course, it means "pertaining to a wedding or bride", but before it used to mean "wedding feast". The new definition happened because people saw what they thought was the suffix -al and assumed that the newer meaning is correct; they were wrong. Indeed, bridal is from the Old English word brydealo, which also meant "wedding feast". But the plot thickens! Brydealo is from bryd ealu, which literally meant "bride ale", as in the alcoholic beverage. The beverage-to-meal transition was done synecdochally, but is nevertheless fascinating. Bryd is from Proto-Germanic brudiz, which has unknown origin, and ale is from Proto-Indo-European helut (meaning "beer"), through Proto-Germanic alu. Next time you get a bit tipsy at a wedding, remember to drink some bridal.

We always think it's sexist for a woman to assume the role of housewife, and nowadays many families also have stay-at-home dads, or, as influenced by housewife, househusbands. This latter word is a sinful mangling of a nice English word, and redundant on top of that. To explain, the word husband comes from the Old English term husbunda, or, quite literally, "male master of a house". This is probably from Old Norse husbundi, because its components definitely are: hus meant "house" and bondi generally meant "denizen" or "resident" (so a househusband is a "house house resident"). Hus is a very Germanic word, from PGmc husa and an unknown PIE source. Bondi, through Proto-Germanic buana ("dwell"), is from Proto-Indo-European bhuh, "to become". Interestingly, husbandry, the "cultivation of plants and animals", traces to that old meaning of "master of a house", which was extended to "master of a farm", then "farming" in general.

|

AUTHORHello! I'm Adam Aleksic. I have a linguistics degree from Harvard University, where I co-founded the Harvard Undergraduate Linguistics Society and wrote my thesis on Serbo-Croatian language policy. In addition to etymology, I also really enjoy traveling, trivia, philosophy, board games, conlanging, and art history.

Archives

December 2023

TAGS |